Honour amongst thieves

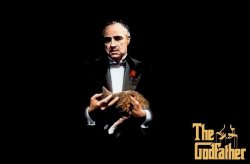

The Godfather (1972)

R16, 168 minutes

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Starring Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan

In 1972, director Francis Ford Coppola translated Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather to the big screen. It and its two sequels established all involved in the production as infamous masters of the cinematic form. This review will focus on the picture’s thematic musings on loyalty.

The Godfather begins with a tightly framed close-up of a man’s face. His daughter has been attacked recently, and the United States’ police force is unable to endorse his quest for retributive “justice”. The camera pulls backwards as he outlines his dilemma to Marlon Brando’s brooding silhouette. His size diminishes within a room of burly gangsters, and we understand that his private battle will always be fought against insignificance: within the presence of the titular Godfather, the state of New York, and the wider hostile culture of American urban life.

It is an effective, intimate opening for a film of grandiose proportions, and its tiny presence within the narrative highlights this man’s struggle to be heard. In this case, his desire for help is ridiculed, because the Don “can’t remember the last time that you invited me to your house for a cup of coffee.” In short, the scene says that alliances can’t be relied upon in times of need unless they’re strengthened during peacetimes of plenty.

The Corleone family is introduced through a series of lilting stereotypes. Set at a wedding, these do a good job establishing the group’s patriarchy. We only meet the blushing bride of the family from a distance, while the men are given dramatic scenes battling the press and FBI. A character says, “In Sicily, women are more dangerous than shotguns.” The implication in the statement is that a shotgun is not lethal until it is loaded, and the American migrant experience has taught second-generation gangsters to keep their women subjugated, beaten, belittled and silenced.

How can loyalty flourish in such an atmosphere? The question is easily related to wartime trench diggers, or colonial slaves. A society of fear oppresses the majority, and only a few are brave enough to query the regime they are ruled under. Kay, the outsider wife with college training, undermines her husband’s succession to the title of Godfather with a singular remark. She does not need bullets to make her messages heard. Her willingness to stand up and be accounted for as a woman is met by a closing door in the stunning final shot of the picture. The supposedly hardened, family-oriented gangsters of the picture would take this disrespect as reason for murderous revenge, while Kay displays a patient ability to stand outside, waiting for resolution. She becomes tougher than a bullet-proof vest, and simultaneously shows her true, loving loyalty.

The Corleones are under strict instructions to keep their views and disagreements “within the family”. The Godfather’s script is the same way: utterly insular, it always keeps the characters within an arm’s reach of the Don’s sphere of influence. This is reasonably unique for the gangster genre – because characters like “investigative reporters” or “honest detectives” typically show morality’s flipside – and it quickly builds a feeling of inescapable awe in the gangster culture.

Michael is the only member of the family that truly sees the organisation as hierarchical. At one point he says, “My father is … like a president …” But how does one get the attention of a sub-country’s “president” without being seen as disrespectful or disloyal? As interesting as it is to watch intemperate men clamber for mana amongst their peers, The Godfather suggests outwardly peaceful characters are far more likely to gain favour with a leader. Michael’s own rise to power begins with a few whispered words. His loyalty is as passionate as those around him, but he focuses it humbly on the leader, rather than rashly on the collective group. What this suggests about the republics and democracies of the “New World” – as opposed to the monarchies and dictatorships of the “Old World” – is anybody’s guess.

Metaphors aside, The Godfather shows us that respect is worthless if one does not understand how to be respectable.