Performance comparison: counting words in Python, Go, C++, C, AWK, Forth, and Rust

March 2021

Summary: I describe a simple interview problem (counting frequencies of unique words), solve it in various languages, and compare performance across them. For each language, I’ve included a simple, idiomatic solution as well as a more optimized approach via profiling.

Go to: Constraints | Python Go C++ C AWK Forth Rust Shell Others | Results!

I’ve conducted many coding interviews over the past few years, and one of the questions I like to ask is this:

Write a program to count the frequencies of unique words from standard input, then print them out with their frequencies, ordered most frequent first. For example, given this input:

The foo the foo the defenestration theThe program should print the following:

the 4 foo 2 defenestration 1

I think this is a good interview question because it’s somewhat harder to solve than FizzBuzz, but it doesn’t suffer from the “invert a binary tree on this whiteboard” issue. It’s the kind of thing a programmer might have to write a script for in real life, and it shows whether they understand file I/O, hash tables (maps), and how to use their language’s sort function. There’s a little bit of trickiness in the sorting part, because most hash tables aren’t ordered, and if they are, it’s by key or insertion order and not by value.

After the candidate has a basic solution, you can push it in all sorts of different directions: what about capitalization? punctuation? how does it order two words with the same frequency? what’s the performance bottleneck likely to be? how does it fare in terms of big-O? what’s the memory usage? roughly how long would your program take to process a 1GB file? would your solution still work for 1TB? and so on. Or you can take it in a “software engineering” direction and talk about error handling, testability, turning it into a hardened command line utility, etc.

A basic solution reads the file line-by-line, converts to lowercase, splits each line into words, and counts the frequencies in a hash table. When that’s done, it converts the hash table to a list of word-count pairs, sorts by count (largest first), and prints them out.

In Python, one obvious solution using a plain dict might look like this (imports elided):

counts = {}

for line in sys.stdin:

words = line.lower().split()

for word in words:

counts[word] = counts.get(word, 0) + 1

pairs = sorted(counts.items(), key=lambda kv: kv[1], reverse=True)

for word, count in pairs:

print(word, count)

If the candidate was a Pythonista, they might use collections.defaultdict or even collections.Counter – see below for code using the latter. In that case I’d ask them how it worked under the hood, or how they might solve it with a plain dictionary.

Incidentally, this problem set the scene for a wizard duel between two computer scientists several decades ago. In 1986, Jon Bentley asked Donald Knuth to show off “literate programming” with a solution to this problem, and he came up with an exquisite, ten-page Knuthian masterpiece. Then Doug McIlroy (the inventor of Unix pipelines) replied with a one-liner Unix shell version using tr, sort, and uniq.

Image credit comic.browserling.com/97.

In any case, I’ve been playing with this problem for a while now, and I wanted to see what the program would look like in various languages, and how fast they would run, both with a simple idiomatic solution and with a more optimized version. I’m including large snippets of code in the article, but full source for each version is in my benhoyt/countwords repository. Or you can cheat and jump straight to the performance results.

Problem statement and constraints

Each program must read from standard input and print the frequencies of unique, space-separated words, in order from most frequent to least frequent. To keep our solutions simple and consistent, here are the (self-imposed) constraints I’m working against:

- Case: the program must normalize words to lowercase, so “The the THE” should appear as “the 3” in the output.

- Words: anything separated by whitespace – ignore punctuation. This does make the program less useful, but I don’t want this to become a tokenization battle.

- ASCII: it’s okay to only support ASCII for the whitespace handling and lowercase operation. Most of the optimized variants do this.

- Ordering: if the frequency of two words is the same, their order in the output doesn’t matter. I use a normalization script to ensure the output is correct.

- Threading: it should run in a single thread on a single machine (though I often discuss concurrency in my interviews).

- Memory: don’t read whole file into memory. Buffering it line-by-line is okay, or in chunks with a maximum buffer size of 64KB. That said, it’s okay to keep the whole word-count map in memory (we’re assuming the input is text in a real language, not full of randomized unique words).

- Text: assume that the input file is text, with “reasonable” length lines shorter than the buffer size.

- Safe: even for the optimized variants, try not to use unsafe language features, and don’t drop down to assembly.

- Hashing: don’t roll our own hash table (with the exception of the optimized C version).

- Stdlib: only use the language’s standard library functions.

Our test input file will be the text of the King James Bible, concatenated ten times. I sourced this from Gutenberg.org, replaced smart quotes with the ASCII quote character, and used cat to multiply it by ten to get the 43MB reference input file.

So let’s get coding! The solutions below are in the order I solved them.

Python

An idiomatic Python version would probably use collections.Counter. Python’s collections library is really nice – thanks Raymond Hettinger! It’s about as simple as you can get:

counts = collections.Counter()

for line in sys.stdin:

words = line.lower().split()

counts.update(words)

for word, count in counts.most_common():

print(word, count)

This is Unicode-aware and is probably what I’d write in “real life”. It’s actually quite efficient, because all the low-level stuff is really done in C: reading the file, converting to lowercase and splitting on whitespace, updating the counter, and the sorting that Counter.most_common does.

But let’s try to optimize! Python comes with a profiling module called cProfile. It’s easy to use – simply run your program using python3 -m cProfile. I’ve commented out the final print call to avoid the profiling output mixing with the program’s output – it’s fairly negligible anyway. Here’s the output (-s tottime sorts by total time in each function):

$ python3 -m cProfile -s tottime simple.py <kjvbible_x10.txt

6997799 function calls (6997787 primitive calls) in 3.872 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

998170 1.361 0.000 1.361 0.000 {built-in method _collections._count_elements}

1 0.911 0.911 3.872 3.872 simple.py:1(<module>)

998170 0.415 0.000 0.415 0.000 {method 'split' of 'str' objects}

998171 0.405 0.000 2.388 0.000 __init__.py:608(update)

998170 0.270 0.000 0.622 0.000 {built-in method builtins.isinstance}

998170 0.182 0.000 0.351 0.000 abc.py:96(__instancecheck__)

998170 0.170 0.000 0.170 0.000 {built-in method _abc._abc_instancecheck}

998170 0.134 0.000 0.134 0.000 {method 'lower' of 'str' objects}

5290 0.009 0.000 0.018 0.000 codecs.py:319(decode)

5290 0.009 0.000 0.009 0.000 {built-in method _codecs.utf_8_decode}

1 0.007 0.007 0.007 0.007 {built-in method builtins.sorted}

7/1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method _abc._abc_subclasscheck}

1 0.000 0.000 0.007 0.007 __init__.py:559(most_common)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 __init__.py:540(__init__)

1 0.000 0.000 3.872 3.872 {built-in method builtins.exec}

7/1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 abc.py:100(__subclasscheck__)

7 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 _collections_abc.py:392(__subclasshook__)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'disable' of '_lsprof.Profiler' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'items' of 'dict' objects}

We can see a number of things here:

- 998,170 is the number of lines in the input, and because we’re reading line-by-line, we’re calling functions and executing the Python loop that many times.

- The large amount of time spent in

simple.pyitself shows how (relatively) slow it is to execute Python bytecode – the main loop is pure Python, again executed 998,170 times. str.splitis relatively slow, presumably because it has to allocate and copy many strings.Counter.updatecallsisinstance, which adds up. I thought about calling the C function_count_elementsdirectly, but that’s an implementation detail and I decided it fell into the “unsafe” category.

The main thing we need to do is reduce the number of times around the main Python loop, and hence reduce the number of calls to all those functions. So let’s read it in 64KB chunks:

counts = collections.Counter()

remaining = ''

while True:

chunk = remaining + sys.stdin.read(64*1024)

if not chunk:

break

last_lf = chunk.rfind('\n') # process to last LF character

if last_lf == -1:

remaining = ''

else:

remaining = chunk[last_lf+1:]

chunk = chunk[:last_lf]

counts.update(chunk.lower().split())

for word, count in counts.most_common():

print(word, count)

Instead of our main loop processing 42 characters at a time (the average line length), we’re processing 65,536 at a time (less the partial line at the end). We’re still reading and processing the same number of bytes, but we’re now doing most of it in C rather than in the Python loop. Many of the optimized solutions use this basic approach – process things in bigger chunks.

The profiling output looks much better now. The _count_elements and str.split functions are still taking most of the time, but they’re only being called 662 times instead 998170 (on roughly 64KB at a time rather than 42 bytes):

$ python3 -m cProfile -s tottime optimized.py <kjvbible_x10.txt

7980 function calls (7968 primitive calls) in 1.280 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

662 0.870 0.001 0.870 0.001 {built-in method _collections._count_elements}

662 0.278 0.000 0.278 0.000 {method 'split' of 'str' objects}

1 0.080 0.080 1.280 1.280 optimized.py:1(<module>)

662 0.028 0.000 0.028 0.000 {method 'lower' of 'str' objects}

663 0.010 0.000 0.016 0.000 {method 'read' of '_io.TextIOWrapper' objects}

1 0.007 0.007 0.007 0.007 {built-in method builtins.sorted}

664 0.004 0.000 0.004 0.000 {built-in method _codecs.utf_8_decode}

663 0.001 0.000 0.872 0.001 __init__.py:608(update)

664 0.001 0.000 0.005 0.000 codecs.py:319(decode)

662 0.001 0.000 0.001 0.000 {built-in method builtins.isinstance}

662 0.000 0.000 0.001 0.000 {built-in method _abc._abc_instancecheck}

662 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'rfind' of 'str' objects}

664 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 codecs.py:331(getstate)

662 0.000 0.000 0.001 0.000 abc.py:96(__instancecheck__)

7/1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method _abc._abc_subclasscheck}

1 0.000 0.000 0.007 0.007 __init__.py:559(most_common)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 __init__.py:540(__init__)

7/1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 abc.py:100(__subclasscheck__)

1 0.000 0.000 1.280 1.280 {built-in method builtins.exec}

7 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 _collections_abc.py:392(__subclasshook__)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'disable' of '_lsprof.Profiler' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'items' of 'dict' objects}

I also found that with the Python solution, reading and processing bytes vs str doesn’t make a noticeable difference (the utf_8_decode is relatively far down the list). In addition, any buffer size above about 2KB is not much slower than 64KB – I’ve noticed many systems have a default buffer size of 4KB, which seems very reasonable in light of that.

I tried various other ways to improve performance, but this was about the best I could manage with standard Python. (I tried running it using the PyPy optimizing compiler, but it’s significantly slower for some reason.) Trying to optimize at the byte level just makes no sense in Python (or leads to a 10-100x slowdown) – any per-character processing has to be done in C. Let me know if you find a better approach.

Go

A simple, idiomatic Go version would probably use bufio.Scanner with ScanWords as the split function. Go doesn’t have anything like Python’s collection.Counter, but it’s easy to use a map[string]int for counting, and a slice of word-count pairs for the sort operation:

func main() {

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(os.Stdin)

scanner.Split(bufio.ScanWords)

counts := make(map[string]int)

for scanner.Scan() {

word := strings.ToLower(scanner.Text())

counts[word]++

}

if err := scanner.Err(); err != nil {

fmt.Fprintln(os.Stderr, err)

os.Exit(1)

}

var ordered []Count

for word, count := range counts {

ordered = append(ordered, Count{word, count})

}

sort.Slice(ordered, func(i, j int) bool {

return ordered[i].Count > ordered[j].Count

})

for _, count := range ordered {

fmt.Println(string(count.Word), count.Count)

}

}

type Count struct {

Word string

Count int

}

The simple Go version is significantly faster than the simple Python version, but only a little bit faster than the optimized Python version (and almost double the number of lines of code – there’s definitely more boilerplate and low-level concerns).

To use Go’s profiler, you have to add a few lines of code to the start of your program (in addition to import "runtime/pprof"):

f, err := os.Create("cpuprofile")

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "could not create CPU profile: %v\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

if err := pprof.StartCPUProfile(f); err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "could not start CPU profile: %v\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

defer pprof.StopCPUProfile()

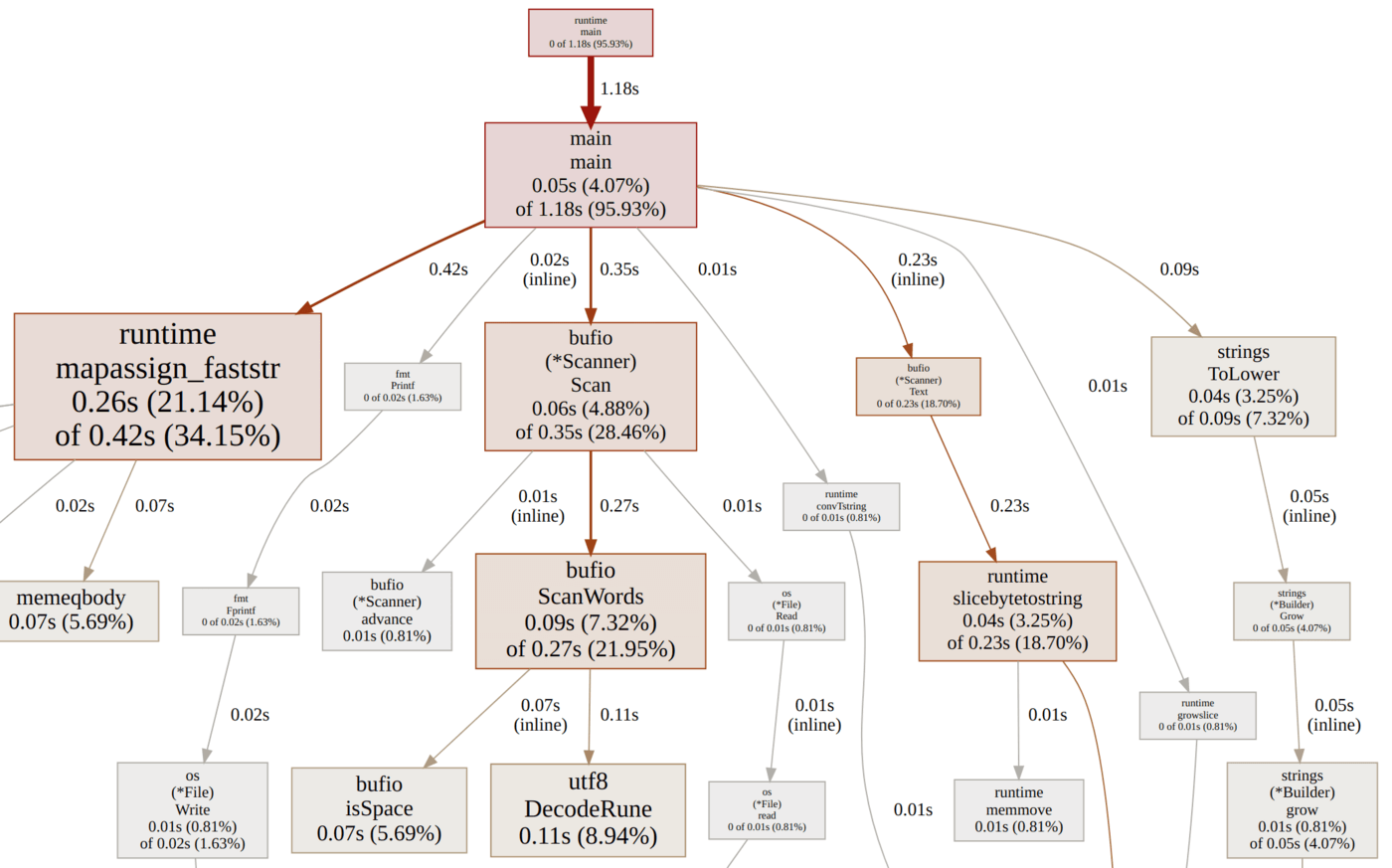

Once you’ve run the program, you can view the CPU profile using this command (click to view the image full size):

$ go tool pprof -http=:7777 cpuprofile

Serving web UI on http://localhost:7777

The results are interesting, though not unexpected – the operations in the per-word hot loop take all the time. A good chunk of the time is spent in the scanner, and another chunk is spent allocating strings to insert into the map, so let’s try to optimize both of those parts.

To improve scanning, we’ll do the word scanning and convert to ASCII lowercase as we go. To reduce the allocations, we’ll use a map[string]*int instead of map[string]int so we only have to allocate once per unique word, instead of for every increment (Martin Möhrmann gave me this tip on the Gophers Slack #performance channel).

Note that it took me a few iterations and profiling passes to get to this result. One in-between step was to still use bufio.Scanner but with a custom split function, scanWordsASCII. However, it’s a bit faster, and not any harder, to avoid bufio.Scanner altogether. Another thing I tried was a custom hash table, but I decided that was out of scope for the Go version, and it’s not much faster than the map[string]*int in any case.

My original optimized code had a subtle bug which resulted in incorrect output some of the time: if Read did a partial read (which happens but is not common) and the bytes read didn’t include a linefeed character, the code would split the last word in the middle and count it as two words. This just goes to show how easy it is to break things when optimizing (and how subtle the semantics of Go’s io.Reader are).

In fact, in the original version of this article I’d prophesied that this might happen:

It’s trickier code, and there is lots of potential for off-by-one errors (I’d be surprised if there isn’t some bug already).

In any case, it’s fixed now. Thanks to Miguel Angel for noticing the issue and simplifying the code.

func main() {

var word []byte

buf := make([]byte, 64*1024)

counts := make(map[string]*int)

for {

// Read input in 64KB blocks till EOF.

n, err := os.Stdin.Read(buf)

if err != nil && err != io.EOF {

fmt.Fprintln(os.Stderr, err)

os.Exit(1)

}

if n == 0 {

break

}

// Count words in the buffer.

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

c := buf[i]

// Found a whitespace char, count last word.

if c <= ' ' {

if len(word) > 0 {

increment(counts, word)

word = word[:0] // reset word buffer

}

continue

}

// Convert to ASCII lowercase as we go.

if c >= 'A' && c <= 'Z' {

c = c + ('a' - 'A')

}

// Add non-space char to word buffer.

word = append(word, c)

}

}

// Count last word, if any.

if len(word) > 0 {

increment(counts, word)

}

// Convert to slice of Count, sort by count descending, print.

ordered := make([]Count, 0, len(counts))

for word, count := range counts {

ordered = append(ordered, Count{word, *count})

}

sort.Slice(ordered, func(i, j int) bool {

return ordered[i].Count > ordered[j].Count

})

for _, count := range ordered {

fmt.Println(count.Word, count.Count)

}

}

func increment(counts map[string]*int, word []byte) {

if p, ok := counts[string(word)]; ok {

// Word already in map, increment existing int via pointer.

*p++

return

}

// Word not in map, insert new int.

n := 1

counts[string(word)] = &n

}

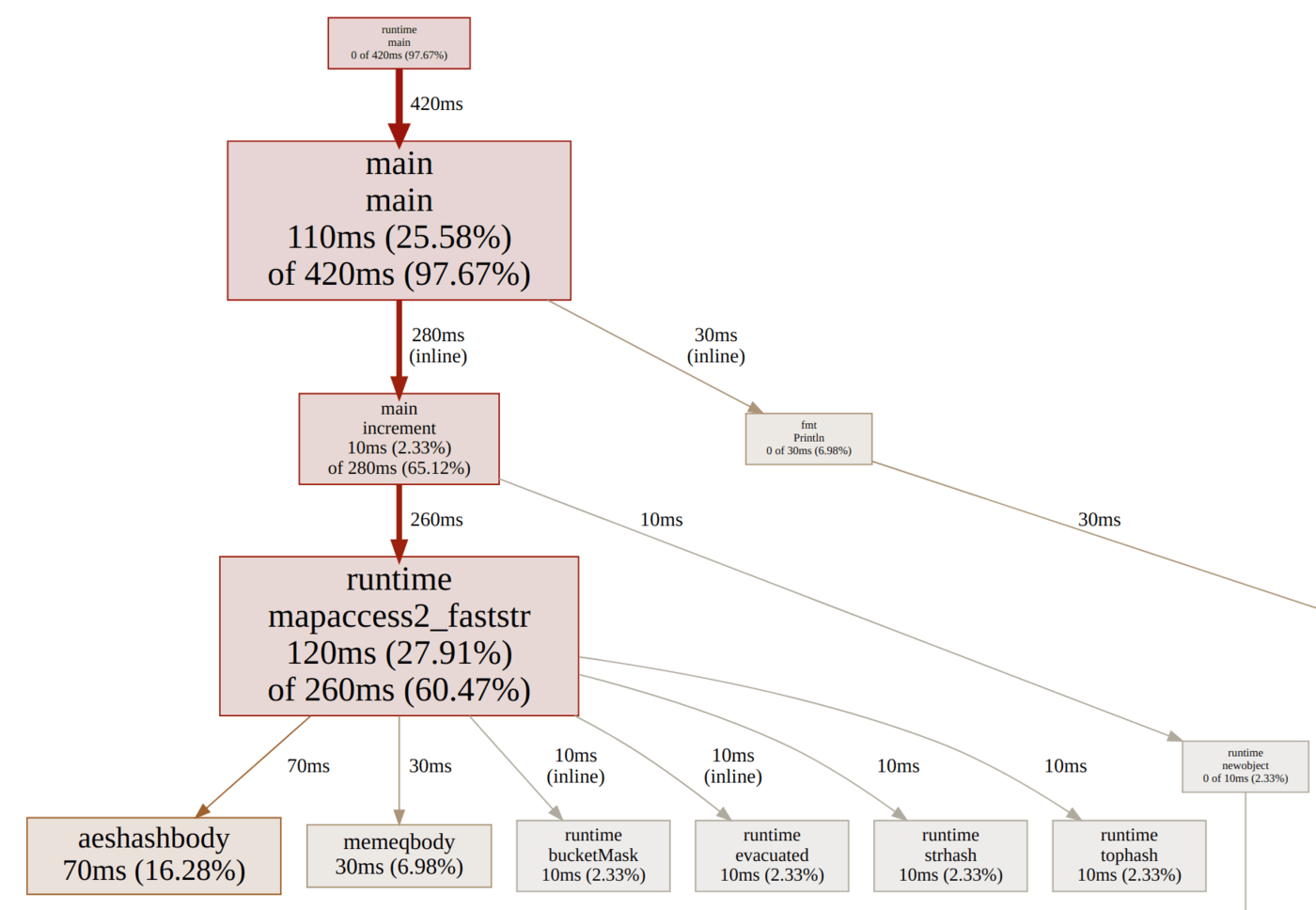

The profiling results are now very flat – almost everything’s in the main loop or the map access:

It was a fun exercise, and Go gives you a fair bit of low-level control (and you could go quite a lot further – memory mapped I/O, a custom hash table, etc). However, programmer time is valuable, so it’s always a trade-off. In practice I’d probably stick with a bufio.Scanner with ScanWords, bytes.ToLower, and the map[string]*int trick.

C++

C++ has come a long way since I last used it seriously: lots of goodies in C++11, and then more in C++14, 17, and 20. Features, features everywhere! It’s definitely a lot terser than old-school C++, though the error messages are still a mess. Here’s the simple version I came up with (with some help from Code Review Stack Exchange to make it a bit more idiomatic):

int main() {

std::string word;

std::unordered_map<std::string, int> counts;

while (std::cin >> word) {

std::transform(word.begin(), word.end(), word.begin(),

[](unsigned char c){ return std::tolower(c); });

++counts[word];

}

if (std::cin.bad()) {

std::cerr << "error reading stdin\n";

return 1;

}

std::vector<std::pair<std::string, int>> ordered(counts.begin(),

counts.end());

std::sort(ordered.begin(), ordered.end(),

[](auto const& a, auto const& b) { return a.second>b.second; });

for (auto const& count : ordered) {

std::cout << count.first << " " << count.second << "\n";

}

}

When optimizing this, the first thing to do is compile with optimizations enabled (g++ -O2). I kind of like the fact that with Go you don’t have to worry about this – optimizations are always on.

I noticed that I/O was comparatively slow. It turns out there is a magic incantation you can recite at the start of your program to disable synchronizing with the C stdio functions after each I/O operation. This line makes it run almost twice as fast:

ios::sync_with_stdio(false);

GCC can generate a profiling report for use with gprof. Here’s what a few lines of it looks like – I kid you not:

index % time self children called name

13 frame_dummy [1]

[1] 100.0 0.01 0.00 0+13 frame_dummy [1]

13 frame_dummy [1]

-----------------------------------------------

0.00 0.00 32187/32187 std::vector<std::pair\

<std::__cxx11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocat\

or<char> >, int>, std::allocator<std::pair<std::__cxx11::basic_string<\

char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >, int> > >::vector\

<std::__detail::_Node_iterator<std::pair<std::__cxx11::basic_string<ch\

ar, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> > const, int>, false,\

true>, void>(std::__detail::_Node_iterator<std::pair<std::__cxx11::ba\

sic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> > const,\

int>, false, true>, std::__detail::_Node_iterator<std::pair<std::__cx\

x11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >\

const, int>, false, true>, std::allocator<std::pair<std::__cxx11::bas\

ic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >, int> >\

const&) [11]

[8] 0.0 0.00 0.00 32187 void std::__cxx11::basic_\

string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >::_M_constr\

uct<char*>(char*, char*, std::forward_iterator_tag) [8]

-----------------------------------------------

0.00 0.00 1/1 __libc_csu_init [17]

[9] 0.0 0.00 0.00 1 _GLOBAL__sub_I_main [9]

...

Ah, C++ templates. Call me old-school, but I do prefer the names malloc and scanf over std::basic_istream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator>><char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >(std::basic_istream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, std::__cxx11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >&).

I really didn’t feel like deciphering this output, so I kind of gave up and spent my energy on the optimized C version. There’s obviously a lot more pushing you could do with C++. However, I suspect it would end up getting more and more low-level and more C-like (at least with my limited knowledge of modern C++), so if you want to see more of that, go to the C variants below.

I used the Valgrind profiler (Callgrind) in the C version – see the section below for notes on that. Andrew Gallant pointed out that I could try the Linux perf tool (specifically perf record and perf report) – it does look better than gprof.

Update: Jussi Pakkanen and Adev and others optimized the C++ version. Thanks!

C

C is a beautiful beast that will never die: fast, unsafe, and simple (for some value of “simple”). I still like it, because (unlike C++) I can understand it, and I can go as low-level as I want. It’s also ubiquitous (the Linux kernel, Redis, PostgreSQL, SQLite, many many libraries … the list is endless), and it’s not going away anytime soon. So let’s try a C version.

Unfortunately, C doesn’t have a hash table data structure in its standard library. However, there is libc, which has the hcreate and hsearch hash table functions, so we’ll make a small exception and use those libc-but-not-stdlib functions. In the optimized version we’ll roll our own hash table.

One minor annoyance with hcreate is you have to specify the maximum table size up-front. I know the number of unique words is about 30,000, so we’ll make it 60,000 for now.

#define MAX_UNIQUES 60000

typedef struct {

char* word;

int count;

} count;

// Comparison function for qsort() ordering by count descending.

int cmp_count(const void* p1, const void* p2) {

int c1 = ((count*)p1)->count;

int c2 = ((count*)p2)->count;

if (c1 == c2) return 0;

if (c1 < c2) return 1;

return -1;

}

int main() {

// The hcreate hash table doesn't provide a way to iterate, so

// store the words in an array too (also used for sorting).

count* words = calloc(MAX_UNIQUES, sizeof(count));

int num_words = 0;

// Allocate hash table.

if (hcreate(MAX_UNIQUES) == 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "error creating hash table\n");

return 1;

}

char word[101]; // 100-char word plus NUL byte

while (scanf("%100s", word) != EOF) {

// Convert word to lower case in place.

for (char* p = word; *p; p++) {

*p = tolower(*p);

}

// Search for word in hash table.

ENTRY item = {word, NULL};

ENTRY* found = hsearch(item, FIND);

if (found != NULL) {

// Word already in table, increment count.

int* pn = (int*)found->data;

(*pn)++;

} else {

// Word not in table, insert it with count 1.

item.key = strdup(word); // need to copy word

if (item.key == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "out of memory in strdup\n");

return 1;

}

int* pn = malloc(sizeof(int));

if (pn == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "out of memory in malloc\n");

return 1;

}

*pn = 1;

item.data = pn;

ENTRY* entered = hsearch(item, ENTER);

if (entered == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "table full, increase MAX_UNIQUES\n");

return 1;

}

// And add to words list for iterating.

words[num_words].word = item.key;

num_words++;

}

}

// Iterate once to add counts to words list, then sort.

for (int i = 0; i < num_words; i++) {

ENTRY item = {words[i].word, NULL};

ENTRY* found = hsearch(item, FIND);

if (found == NULL) { // shouldn't happen

fprintf(stderr, "key not found: %s\n", item.key);

return 1;

}

words[i].count = *(int*)found->data;

}

qsort(&words[0], num_words, sizeof(count), cmp_count);

// Iterate again to print output.

for (int i = 0; i < num_words; i++) {

printf("%s %d\n", words[i].word, words[i].count);

}

return 0;

}

There’s a fair bit of boilerplate (mostly for memory allocation and error checking), but as far as C goes, I don’t think it’s too bad. The tricky stuff is mostly hidden – tokenization behind scanf, and hash table operations behind hsearch. It’s also relatively fast out of the box, and very small (a 17KB executable on Linux).

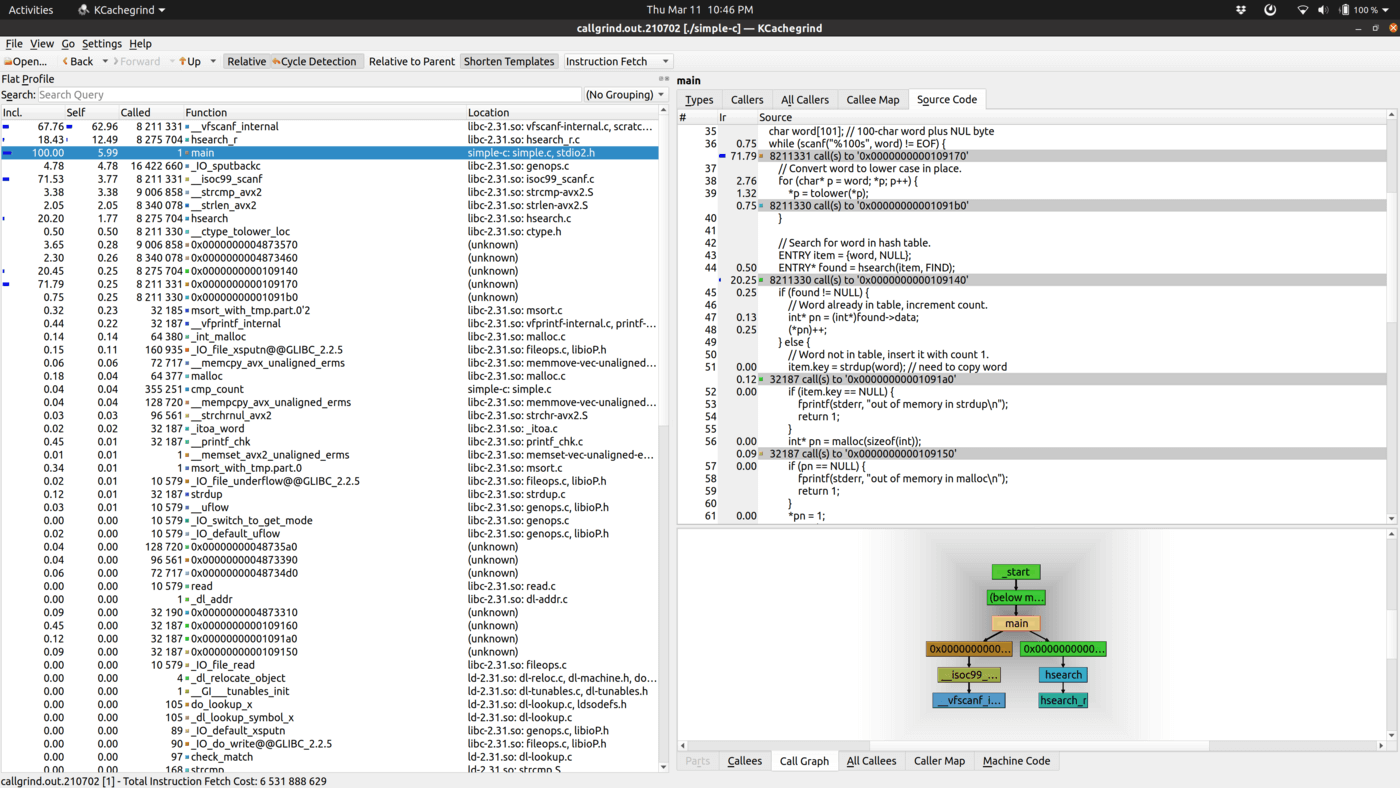

To profile, I tried using gprof, but it didn’t show anything useful (maybe it’s not sampling often enough?), so I investigated using the Valgrind profiler, Callgrind. This was the first time I’ve used it, but it seems like an amazing and powerful tool.

After building with gcc -g, I ran this command to generate the profile:

valgrind --tool=callgrind ./simple-c <kjvbible_x10.txt >/dev/null

Not surprisingly, it shows that scanf is the major culprit, followed by hsearch. So here’s where we’ll go a bit crazy with optimization. I want to focus on three things:

- Read the file in chunks, like we did in Go and Python. This will avoid the overhead of

scanf. - Process the bytes only once, or at least as few times as possible – I’ll be converting to lowercase and calculating the hash as we’re tokenizing into words.

- Implement our own hash table using the fast FNV-1 hash function.

#define BUF_SIZE 65536

#define HASH_LEN 65536 // must be a power of 2

#define FNV_OFFSET 14695981039346656037UL

#define FNV_PRIME 1099511628211UL

// Used both for hash table buckets and array for sorting.

typedef struct {

char* word;

int word_len;

int count;

} count;

// Comparison function for qsort() ordering by count descending.

int cmp_count(const void* p1, const void* p2) {

int c1 = ((count*)p1)->count;

int c2 = ((count*)p2)->count;

if (c1 == c2) return 0;

if (c1 < c2) return 1;

return -1;

}

count* table;

int num_unique = 0;

// Increment count of word in hash table (or insert new word).

void increment(char* word, int word_len, uint64_t hash) {

// Make 64-bit hash in range for items slice.

int index = (int)(hash & (uint64_t)(HASH_LEN-1));

// Look up key, using direct match and linear probing if not found.

while (1) {

if (table[index].word == NULL) {

// Found empty slot, add new item (copying key).

char* word_copy = malloc(word_len);

if (word_copy == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "out of memory\n");

exit(1);

}

memmove(word_copy, word, word_len);

table[index].word = word_copy;

table[index].word_len = word_len;

table[index].count = 1;

num_unique++;

return;

}

if (table[index].word_len == word_len &&

memcmp(table[index].word, word, word_len) == 0) {

// Found matching slot, increment existing count.

table[index].count++;

return;

}

// Slot already holds another key, try next slot (linear probe).

index++;

if (index >= HASH_LEN) {

index = 0;

}

}

}

int main() {

// Allocate hash table buckets.

table = calloc(HASH_LEN, sizeof(count));

if (table == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "out of memory\n");

return 1;

}

char buf[BUF_SIZE];

int offset = 0;

while (1) {

// Read file in chunks, processing one chunk at a time.

size_t num_read = fread(buf+offset, 1, BUF_SIZE-offset, stdin);

if (num_read+offset == 0) {

break;

}

// Find last space or linefeed in buf and process up to there.

int space;

for (space = offset+num_read-1; space>=0; space--) {

char c = buf[space];

if (c <= ' ') {

break;

}

}

int num_process = (space >= 0) ? space : (int)num_read+offset;

// Scan chars to process: tokenize, lowercase, and hash as we go.

int i = 0;

while (1) {

// Skip whitespace before word.

for (; i < num_process; i++) {

char c = buf[i];

if (c > ' ') {

break;

}

}

// Look for end of word, lowercase and hash as we go.

uint64_t hash = FNV_OFFSET;

int start = i;

for (; i < num_process; i++) {

char c = buf[i];

if (c <= ' ') {

break;

}

if (c >= 'A' && c <= 'Z') {

c += ('a' - 'A');

buf[i] = c;

}

hash *= FNV_PRIME;

hash ^= (uint64_t)c;

}

if (i <= start) {

break;

}

// Got a word, increment count in hash table.

increment(buf+start, i-start, hash);

}

// Move down remaining partial word.

if (space >= 0) {

offset = (offset+num_read-1) - space;

memmove(buf, buf+space+1, offset);

} else {

offset = 0;

}

}

count* ordered = calloc(num_unique, sizeof(count));

for (int i=0, i_unique=0; i<HASH_LEN; i++) {

if (table[i].word != NULL) {

ordered[i_unique++] = table[i];

}

}

qsort(ordered, num_unique, sizeof(count), cmp_count);

for (int i=0; i<num_unique; i++) {

printf("%.*s %d\n",

ordered[i].word_len, ordered[i].word, ordered[i].count);

}

return 0;

}

At around 150 lines (including blanks and comments), it’s definitely the biggest program yet, but not too bad! As you can see, rolling your own hash table with linear probing is not a lot of code. It’s not great to have a fixed size table, but adding dynamic resizing is just busy-work, and doesn’t slow down the running time significantly, so I’ve left that as an exercise for the reader.

It’s still only a 17KB executable (that’s what I love about C). And, unsurprisingly, this is the fastest version – a little bit faster than the optimized Go version, because we’ve rolled our own custom hash table, and we’re processing fewer bytes.

As shown in the results, this version is only about 15% slower than wc -w on the same input (with LC_ALL=C to allow ASCII-only whitespace handling). And all the wc utility has to do is tokenize words, not count unique words, so it doesn’t need a hash table.

This program is significantly slower than the incredible GNU grep, of course. There’s a semi-famous mailing list message from 2010 by Mike Haertel, original author of GNU grep, on why GNU grep is fast. It’s fascinating reading – however, as Andrew Gallant (author of ripgrep) pointed out to me, that post is somewhat out of date. Mike’s general advice is good, but these days GNU grep is fast not so much due to skipping bytes with the Boyer-Moore algorithm, but because it uses a fast, vectorized implementation of memchr in glibc.

I’m sure there’s further you could go with the C version: investigate memory-mapped I/O, avoid processing byte-at-a-time, use a fancier data structure for counting, etc. But this is quite enough for now!

AWK

AWK is actually a great tool for this job: reading lines and parsing into space-separated words are what it eats for breakfast. One thing AWK can’t do (without resorting to Gawk-specific features) is the sorting, so I’m using the AWK pipe operator to send the output through sort. Here’s the beautifully simple code:

{

for (i = 1; i <= NF; i++)

counts[tolower($i)]++

}

END {

for (k in counts)

print k, counts[k] | "sort -nr -k2"

}

I don’t know of an easy way to profile this at a low level (Gawk does have a profiling mode, but it just shows how many times each line was executed). I also don’t know how to read the input in chunks using AWK or Gawk.

One small tweak I made for the optimized version was to call tolower once per line instead of for every word. The main loop becomes:

{

$0 = tolower($0)

for (i = 1; i <= NF; i++)

counts[$i]++

}

...

We can run this using gawk -b, which puts Gawk into “bytes” mode so it uses ASCII instead of UTF-8. This “optimized” version using gawk -b is about 1.6x as fast as the simple version using straight gawk.

Another “optimization” is to run it using mawk, a faster AWK interpreter than gawk. In this case it’s about 1.7 times as fast as gawk -b. I’m using mawk in the benchmarks for the optimized version.

Interestingly, the Gawk manual has a page on this word-frequency problem, with an example of how to strip out punctuation using AWK’s gsub function.

If you’re interested in learning more about AWK, I’ve written an article about GoAWK, my AWK interpreter written in Go (it’s normally about as fast as Gawk), and also an article for LWN called The State of the AWK, which surveys the “AWK landscape” and digs into the new features in Gawk 5.1.

Forth

Forth was the first programming language I learned (it’s an amazing and mind-expanding language), so I decided to try a Forth version using Gforth. I haven’t written anything in the language for years, but here goes (though I’m not sure it’s valid to call this simple!):

200 constant max-line

create line max-line allot \ Buffer for read-line

wordlist constant counts \ Hash table of words to count

variable num-uniques 0 num-uniques !

\ Convert character to lowercase.

: to-lower ( C -- c )

dup [char] A [ char Z 1+ ] literal within if

32 +

then ;

\ Convert string to lowercase in place.

: lower-in-place ( addr u -- )

over + swap ?do

i c@ to-lower i c!

loop ;

\ Count given word in hash table.

: count-word ( addr u -- )

2dup counts search-wordlist if

\ Increment existing word

>body 1 swap +!

2drop

else

\ Insert new word with count 1

2dup lower-in-place

['] create execute-parsing 1 ,

1 num-uniques +!

then ;

\ Process text in the source buffer (one line).

: process-input ( -- )

begin

parse-name dup

while

count-word

repeat

2drop ;

\ Less-than for words (true if count is *greater* for reverse sort).

: count< ( nt1 nt2 -- )

>r name>interpret >body @

r> name>interpret >body @

> ;

\ ... Definition of "sort" elided ...

\ Append word from wordlist to array at given offset.

: append-word ( addr offset nt -- addr offset+cell true )

>r 2dup + r> swap !

cell+ true ;

\ Show "word count" line for each word, most frequent first.

: show-words ( -- )

num-uniques @ cells allocate throw

0 ['] append-word counts traverse-wordlist drop

dup num-uniques @ sort

num-uniques @ 0 ?do

dup i cells + @

dup name>string type space

name>interpret >body @ . cr

loop

drop ;

: main ( -- )

counts set-current \ Define into counts wordlist

begin

line max-line stdin read-line throw

while

line swap ['] process-input execute-parsing

repeat

drop

show-words ;

It’s not for nothing that Forth has a reputation for being write-only. I used to love the idea of no local variables, but in practice it just means a lot of dup over swap rot. In addition, even Gforth (which has a lot more than ANS standard Forth) doesn’t have fairly basic tools like to-lower or sort, so we have to roll those ourselves (the in-place merge sort was taken from Rosetta Code).

Thankfully hash tables are present via wordlist. This is really intended for defining new Forth words, but with Gforth’s execute-parsing extension it works pretty well for hash tables. And skip and scan work well for the whitespace parsing (thanks comp.lang.forth folks for your help).

For optimizing, it turns out you can run gforth-fast instead of gforth to magically speed things up, so that’s my first optimization (though in the benchmarks, I use gforth-fast for both versions). It looks like gforth-fast avoids call overhead but doesn’t produce good stack traces on error.

I’m far from proficient in Forth these days, and I didn’t really know where to start with profiling in Gforth (though it looks like they have some kind of support for it).

Anton Ertl was very helpful on my comp.lang.forth post, and spent some time trying to optimize this – read the full thread for more information. I’ve hacked together a combination of my program and his optimizations below (modified to read in chunks of 64KB):

\ Start hash table at larger size

15 :noname to hashbits hashdouble ; execute

65536 constant buf-size

create buf buf-size allot \ Buffer for read-file

wordlist constant counts \ Hash table of words to count

variable num-uniques 0 num-uniques !

\ Convert character to lowercase.

: to-lower ( C -- c )

dup [char] A [ char Z 1+ ] literal within if

32 +

then ;

\ Convert string to lowercase in place.

: lower-in-place ( addr u -- )

over + swap ?do

i c@ to-lower i c!

loop ;

\ Count given word in hash table.

: count-word ( c-addr u -- )

2dup counts find-name-in dup if

( name>interpret ) >body 1 swap +! 2drop

else

drop nextname create 1 ,

1 num-uniques +!

then ;

\ Process text in the buffer.

: process-string ( -- )

begin

parse-name dup

while

count-word

repeat

2drop ;

\ Less-than for words (true if count is *greater* for reverse sort).

: count< ( nt1 nt2 -- )

>r name>interpret >body @

r> name>interpret >body @

> ;

\ ... Definition of "sort" elided ...

\ Append word from wordlist to array at given offset.

: append-word ( addr offset nt -- addr offset+cell true )

dup name>string lower-in-place

>r 2dup + r> swap !

cell+ true ;

\ Show "word count" line for each word, most frequent first.

: show-words ( -- )

num-uniques @ cells allocate throw

0 ['] append-word counts traverse-wordlist drop

dup num-uniques @ sort

num-uniques @ 0 ?do

dup i cells + @

dup name>string type space

name>interpret >body @ . cr

loop

drop ;

\ Find last LF character in string, or return -1.

: find-eol ( addr u -- eol-offset|-1 )

begin

1- dup 0>=

while

2dup + c@ 10 = if

nip exit

then

repeat

nip ;

: main ( -- )

counts set-current \ Define into counts wordlist

0 >r \ offset after remaining bytes

begin

\ Read from remaining bytes till end of buffer

buf r@ + buf-size r@ - stdin read-file throw dup

while

\ Process till last LF

buf over r@ + find-eol

dup buf swap ['] process-string execute-parsing

\ Move leftover bytes to start of buf, update offset

dup buf + -rot buf -rot - r@ +

r> drop dup >r move

repeat

drop r> drop

show-words ;

I might still consider using Forth for fun or on tiny embedded systems, but I don’t think it has the ergonomics or the libraries to write programs for general use. For a much richer, more modern take on a Forth-like language, check out Factor.

Rust

I’m a heavy user of Andrew Gallant’s excellent ripgrep code search tool, and I knew he was pretty big into Rust (and optimization), so before publishing this article I asked him if he’d be willing to do a Rust version.

He more than delivered! He wrote simple and optimized versions, which are similar to the Go variants (and very close in speed). But then he wrote three additional versions (some of which use external dependencies):

- A “bonus” version that is similar to the simple version but does Unicode-aware word segmentation and has a few other goodies. Andrew said this is how he’d write it if someone asked for a versatile version.

- A custom hash table version. It’s an approximate port of my C version, and almost as fast.

- A trie version that uses a trie data structure instead of a hash table. Andrew (like me) thought this might be faster, but it turns out to be slightly slower.

His simple version doesn’t use any external dependencies, and is similar to the simple Go and C++ versions (his comments included)

fn main() {

// We don't return Result from main because it prints the debug

// representation of the error. The code below prints the "display"

// or human readable representation of the error.

if let Err(err) = try_main() {

eprintln!("{}", err);

std::process::exit(1);

}

}

fn try_main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let stdin = io::stdin();

let stdin = io::BufReader::new(stdin.lock());

let mut counts: HashMap<String, u64> = HashMap::new();

for result in stdin.lines() {

let line = result?;

for word in line.split_whitespace() {

let canon = word.to_lowercase();

*counts.entry(canon).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

}

let mut ordered: Vec<(String, u64)> = counts.into_iter().collect();

ordered.sort_by(|&(_, cnt1), &(_, cnt2)| cnt1.cmp(&cnt2).reverse());

for (word, count) in ordered {

writeln!(io::stdout(), "{} {}", word, count)?;

}

Ok(())

}

I definitely like what I’ve seen and heard about Rust, and I’d learn it over modern C++ any day, though I understand it’s got a fairly steep learning curve … and quite a few !?&|<> sigils.

For the optimized version, I’ll include his comments here (and copy the code from try_main on):

This version is an approximate port of the optimized Go program. Its buffer handling is slightly simpler: we don’t bother with dealing with the last newline character. (This may appear to save work, but it only saves work once per 64KB buffer, so is likely negligible. It’s just simpler IMO.)

There’s nothing particularly interesting here other than swapping out std’s default hashing algorithm for one that isn’t cryptographically secure.

std uses a cryptographically secure hashing algorithm by default, which is a bit slower. In this particular program, fxhash and fnv seem to perform similarly, with fxhash being a touch faster in my ad hoc benchmarks. If we wanted to really enforce the “no external crate” rule, we could just hand-roll an fnv hash impl ourselves very easily.

fn try_main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let stdin = io::stdin();

let mut stdin = stdin.lock();

let mut counts: HashMap<Vec<u8>, u64> = HashMap::default();

let mut buf = vec![0; 64 * (1<<10)];

let mut offset = 0;

let mut start = None;

loop {

let nread = stdin.read(&mut buf[offset..])?;

if nread == 0 {

if offset > 0 {

increment(&mut counts, &buf[..offset+1]);

}

break;

}

let buf = &mut buf[..offset+nread];

for i in (0..buf.len()).skip(offset) {

let b = buf[i];

if b'A' <= b && b <= b'Z' {

buf[i] += b'a' - b'A';

}

if b == b' ' || b == b'\n' {

if let Some(start) = start.take() {

increment(&mut counts, &buf[start..i]);

}

} else if start.is_none() {

start = Some(i);

}

}

if let Some(ref mut start) = start {

offset = buf.len() - *start;

buf.copy_within(*start.., 0);

*start = 0;

} else {

offset = 0;

}

}

let mut ordered: Vec<(Vec<u8>, u64)> = counts.into_iter().collect();

ordered.sort_by(|&(_, cnt1), &(_, cnt2)| cnt1.cmp(&cnt2).reverse());

for (word, count) in ordered {

writeln!(io::stdout(), "{} {}", std::str::from_utf8(&word)?,

count)?;

}

Ok(())

}

fn increment(counts: &mut HashMap<Vec<u8>, u64>, word: &[u8]) {

// using 'counts.entry' would be more idiomatic here, but doing so

// requires allocating a new Vec<u8> because of its API. Instead, we

// do two hash lookups, but in the exceptionally common case (we see

// a word we've already seen), we only do one and without any allocs.

if let Some(count) = counts.get_mut(word) {

*count += 1;

return;

}

counts.insert(word.to_vec(), 1);

}

Thanks, Andrew!

Unix shell

Let’s try a version with only basic Unix command line tools – this is essentially Doug McIlroy’s solution:

tr 'A-Z' 'a-z' | tr -s ' ' '\n' | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr

It’s quite slow, in part because it has to sort the entire file at once rather than using a hash table for counting (reading the entire file into memory actually goes against the constraints I’ve imposed). However, I was surprised at how much it speeds up if you set the locale of the first sort to C (ASCII-only) – that speeds it up by a factor of 5, which is faster than the algorithmically-better approaches in other languages!

And we can get a bit more performance out of it by using sort -S 2GB to give it a larger buffer (while we’re breaking constraints, we might as well break them properly). Interestingly, sort’s --parallel option doesn’t help at this scale. So the optimized version is as follows:

tr 'A-Z' 'a-z' | tr -s ' ' '\n' | LC_ALL=C sort -S 2G | uniq -c | \

sort -nr

This is fine for relatively small files. If I wanted to process huge files and not read the entire thing into memory to sort, I’d probably reach for the AWK or Python versions.

The output is not quite the same as the others, because the format is “space-prefixed-count word” rather than “word count”, like so:

4 the

2 foo

1 defenestration

We could fix that with something like awk '{ print $2, $1 }', but then we’re using AWK anyway, and we might as well use the more efficient AWK program above.

Other languages

Many readers contributed to the benhoyt/countwords repository to add other popular languages – thank you! (Note that I’m no longer taking new contributions.)

Here’s the list:

- Bash: Jesse Hathaway - not included in benchmarks as it takes over 2 minutes

- C#: John Taylor, Yuriy Ostapenko and Osman Turan

- C# (LINQ): Osman Turan - not run in benchmarks

- C++ optimized version: Jussi Pakkanen, Adev, Nathan Myers

- Common Lisp: Brad Svercl

- Crystal: Andrea Manzini

- D: Ross Lonstein

- F#: Yuriy Ostapenko

- Go: Miguel Angel - simplifying the Go optimized version; Joshua Corbin - adding a parallel Go version for demonstration

- Haskell: Adrien Glauser

- Java: Iulian Pleșoianu

- JavaScript: Dani Biró and Flo Hinze

- Julia: Alessandro Melis

- Kotlin: Kazik Pogoda

- Lua: Flemming Madsen

- Nim: csterritt and euantorano

- OCaml: doesntgolf

- Pascal: Osman Turan

- Perl: Charles Randall

- PHP: Max Semenik

- Ruby: Bill Mill, with input from Niklas

- Rust: Andrew Gallant

- Swift: Daniel Müllenborn

- Tcl: William Ross

- Zig: ifreund and matu3ba and ansingh

Performance results and learnings

Below are the performance numbers of running these programs on my laptop (64-bit Linux with an SSD using these versions). I’m running each test five times and taking the minimum time as the result (see benchmark.py). Each run is basically equivalent to the following command:

time $PROGRAM <kjvbible_x10.txt >/dev/null

The times are in seconds, so lower is better, and the list is ordered by the execution time of the simple version, fastest first. (Note that grep and wc don’t actually solve the word counting problem, they’re just here for comparison.)

| Language | Simple | Optimized | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

grep |

0.04 | 0.04 | grep baseline; optimized sets LC_ALL=C |

wc -w |

0.28 | 0.20 | wc baseline; optimized sets LC_ALL=C |

| Zig | 0.55 | 0.24 | by ifreund and matu3ba and ansingh |

| Nim | 0.77 | 0.49 | by csterritt and euantorano |

| C | 0.96 | 0.23 | |

| Go | 1.12 | 0.40 | |

| OCaml | 1.18 | by Nate Dobbins and Pavlo Khrystenko | |

| Crystal | 1.29 | by Andrea Manzini | |

| Rust | 1.38 | 0.43 | by Andrew Gallant |

| Java | 1.40 | 1.34 | by Iulian Plesoianu |

| PHP | 1.40 | by Max Semenik | |

| C# | 1.50 | 0.82 | by J Taylor, Y Ostapenko, O Turan |

| C++ | 1.69 | 0.27 | optimized by Jussi P, Adev, Nathan M |

| Perl | 1.81 | by Charles Randall | |

| Kotlin | 1.81 | by Kazik Pogoda | |

| F# | 1.81 | 1.60 | by Yuriy Ostapenko |

| JavaScript | 1.88 | 1.10 | by Dani Biro and Flo Hinze |

| D | 2.05 | 0.74 | by Ross Lonstein |

| Python | 2.21 | 1.33 | |

| Lua | 2.50 | 2.00 | by themadsens; runs under luajit |

| Ruby | 3.17 | 2.47 | by Bill Mill |

| AWK | 3.55 | 1.13 | optimized uses mawk |

| Pascal | 3.67 | by Osman Turan | |

| Forth | 4.22 | 1.45 | |

| Swift | 4.23 | by Daniel Muellenborn | |

| Common Lisp | 4.97 | by Brad Svercl | |

| Tcl | 6.82 | by William Ross | |

| Haskell | 12.81 | by Adrien Glauser | |

| Shell | 14.81 | 1.83 | optimized does LC_ALL=C sort -S 2G |

What can we learn from all this? Here are a few thoughts:

- I think it’s the simple, idiomatic versions that are the most telling. This is the code programmers are likely to write in real life.

- You almost certainly shouldn’t write the optimized C version, unless you’re writing a new GNU

wordfreqtool or something. It’s just too easy to get wrong. If you want a fast version in a safe language, I’d recommend Go or Rust. - If you just need a quick solution (which is likely), Python and AWK are amazing for this kind of text processing.

- C++ templates produce such horrible error messages and function names in the profiler, making them almost unreadable.

- I still think this interview question is a good one for a coding question, though obviously I wouldn’t expect a candidate to write one of the optimized solutions on the whiteboard.

- We usually think of I/O as expensive, but I/O isn’t the bottleneck here. In the case of benchmarks, the file is probably cached, but even if not, hard drive read speeds are incredibly fast these days. The tokenization and hash table operations are the bottleneck by a long shot.

This was definitely a fun exercise! I learned a good amount about optimization hot-spots, using the Valgrind profiler, and I wrote some Forth code for the first time in years.

Let me know your thoughts or feedback, or send ideas for improvements (see the discussions on Hacker News, programming Reddit, and Lobsters).

I hope you enjoyed this LLM-free, hand-crafted article.

I’d love it if you sponsored me on GitHub – it will motivate me to work on my open source projects and write more good content. Thanks!