From Go on EC2 to Fly.io: +fun, −$9/mo

February 2023

Go to: Old to new | To-dos | Weddings | Config | Statics | Cron | Load testing | Conclusion

I recently switched two side projects from being hosted on an Amazon EC2 instance to using Fly.io. It was a really good experience: Fly.io just worked. It allowed me to delete about 500 lines of Ansible scripts and config files, and saved me $9 a month.

For the larger of the two projects, I also made a few simplifications while I was at it: I switched from using a CDN for hosting static files to using go:embed with ETag caching, from using cron jobs to simple background goroutines, and from using config files to environment variables.

I left the architecture of both apps the same: each uses a Go net/http server, an SQLite database, and some HTML templates and static files.

It took me about an hour to figure out the basics of Fly.io and move the simpler project, and a couple of evenings to move the more complex one. Fly.io handles the annoying reverse proxy and SSL stuff, deployment is as simple as fly deploy, and there’s a nice dashboard on Fly.io to show me what’s going on.

Old to new

For a long time, I’ve been using a single EC2 instance running Amazon Linux to host these two applications (instance type t2.micro). They’re low-traffic sites, and this worked fine. But even with good tools, it required more setup and babysitting than I cared for.

These are small Go web applications, and as someone pointed out on Hacker News, deploying a Go app is as simple as “Scp the executable and run it. This will work on any Linux vm without any setup.”

As I replied (this was before actually switching to Fly.io):

That’s what I do now. But there’s a bunch more setup:

- Install and configure Caddy to terminate the SSL. Caddy is great, but still stuff to think about and 20 lines of config to figure out.

- Configure systemd to run Caddy and my Go server. Not rocket science, but required me figuring out systemd for the first time and the appropriate 25-line config file for each server.

- Scripts to upgrade Caddy when a new version comes out (it wasn’t in the apt repos when I did this).

- Ansible setup scripts to clone the repo, create users and groups for Caddy and my Go server, copy config files, add cron jobs for backups (150 lines of Ansible YAML).

It looks like you don’t need most of this, or get it without additional configuration with Fly.io and Render.

As I noted after that, the difference between Fly.io and doing it yourself using an EC2 instance is kind of like the difference between Dropbox and what was suggested in that famous Hacker News comment when Dropbox first came out:

For a Linux user, you can already build such a system yourself quite trivially by getting an FTP account, mounting it locally with curlftpfs, and then using SVN or CVS on the mounted filesystem. From Windows or Mac, this FTP account could be accessed through built-in software.

It might be “quite trivial”, but it’s still too much work for lazy developers, let alone non-technical people.

So I’d been looking around for a simple hosting service that would take care of hosting, SSL certificates, and deployment. A couple of years ago I played with Heroku, but they were more expensive, and they pushed you toward using their relatively costly hosted databases (instead of a simple disk volume for SQLite). It looks like this is still the case.

Then more recently I ran into Fly.io and Render. Render actually looks a bit more full-fledged (for example, they support cron jobs), but it wasn’t going to save me any money compared to EC2, so I kept looking.

Fly.io looked more geeky and command line-oriented, which suited me, and their prices are also ridiculously low: free for up to three small virtual machines (I only need two), and $2/month for small VMs after that. It turns out that 1 shared CPU and 256MB of RAM is plenty for a Go app, even with a modest amount of traffic (see load testing).

I use SQLite for both my apps, and Fly.io is all-in on SQLite, so it seemed like a good fit in that respect. They also have an excellent tech blog.

Simple Lists

I wanted to try out Fly.io on the tiny to-do list app that I host for my family (see my article about Simple Lists). It’s written in Go, and is built in the old-school way: HTML rendered by the server, plain old GET and POST with HTML forms, and no JavaScript.

So I installed flyctl (the Fly.io CLI), and first impressions were good! Without changing my source code at all, I typed flyctl launch to see what would happen. A couple of minutes later, my app was up and running on a fly.dev subdomain. Surely it can’t be this simple…

But it kind of was. The tool had auto-generated a fly.toml config file, automatically figured out how to build my Go app, figured out that the app looked for the PORT environment variable and added an entry for PORT=8080. It looks like they use Paketo “build packs” to do this – though I wasn’t familiar with this project before.

The only issue was that it was referencing an SQLite database on the virtual machine’s ephemeral disk, so whenever I deployed, Fly.io would blow away the database.

To fix this, Fly.io has the concept of persistent volumes, so I used the CLI to create one:

$ flyctl volumes create simplelists_data --size=1

The --size=1 means a 1GB volume. That’s quite a lot of to-do list entries … but apparently that’s the smallest size they allow. Fly.io gives you 3GB for free, and charges $0.15/GB per month after that. Storage is cheap!

Then I added the following three lines to fly.toml (the final version is basically what flyctl generated with this added):

[mounts]

source = "simplelists_data"

destination = "/data"

Then everything just worked. Fly.io does daily snapshots of your volumes, which is enough “backup” for this use case. For some reason the snapshots are about 60MB, when I’m only using about 100KB of disk space, but oh well – that’s Fly.io’s problem!

If you want your own instance of Simple Lists, you can clone the repo and type flyctl launch to run it yourself. You’ll need to generate a password hash with simplelists -genpass and set the SIMPLELISTS_PASSHASH secret first.

Gifty Weddings

Gifty Weddings is a wedding gift registry website that helps couples make their own gift registry that’s not tied to a specific store. It’s a medium-sized web application with a Go and SQLite backend and an Elm frontend. Here’s what the home page looks like:

To get Gifty working on Fly.io, I had to make a few changes:

- Make the server take config options as environment variables instead of in a file.

- Embed HTML templates and static files in the Go binary using

go:embedandfs.FS. - Add goroutines for my two background tasks instead of using cron jobs.

Config in environment variables

The first change was a very minor one. I had a Config struct that I loaded using json.Decoder, and I changed that to use os.Getenv. This is a relatively small project, so there’s no need for a fancy library like Viper – the Go standard library works fine.

Here’s roughly what this looks like:

func main() {

cfg := Config{

AWSKey: os.Getenv("GIFTY_AWS_KEY"),

AWSSecret: os.Getenv("GIFTY_AWS_SECRET"),

ListenAddress: getEnvOrDefault("GIFTY_LISTEN_ADDRESS", ":8080"),

DatabasePath: getEnvOrDefault("GIFTY_DATABASE_PATH", "/data/gifty.sqlite"),

...

}

// ... use cfg ...

}

func getEnvOrDefault(name, defaultValue string) string {

value, ok := os.LookupEnv(name)

if !ok {

value = defaultValue

}

return value

}

Hosting static files

Here’s where I had a decision point. I’ve previously advocated using a CDN like Amazon Cloudfront (backed by S3) for hosting static files. I even wrote a Python tool called cdnupload that uploads a website’s static files to S3 with a content-based hash in the filenames to give great caching while avoiding versioning issues. As of a couple of weeks ago, that’s also what I used for Gifty.

That setup is still good for larger, distributed applications – and I like what Fly.io is doing with distributed apps – but for this small website it seemed like overkill. Go’s web server is fine at serving static files, and I knew I could use Last-Modified or ETag headers to solve the caching issue.

So I said goodbye to cdnupload and went all in on go:embed. This landed in Go 1.16: it’s a built-in way to tell the Go compiler to embed your files into the binary and make them accessible as an fs.FS filesystem interface at runtime.

Here’s what that looks like:

// This "go:embed" directive tells Go to embed static/* (recursively),

// and make it accessible as the staticFS variable.

//go:embed static/*

var staticFS embed.FS

func main() {

// Tell the HTTP server to serve staticFS at /static/*

hashFS := hashfs.NewFS(staticFS)

http.Handle("/static/", hashfs.FileServer(hashFS))

// This function is passed to the HTML templating engine,

// allowing templates to generate paths to static files.

// In templates, it's used like this:

//

// <link rel="stylesheet" href="{{static "styles/main.css"}}">

funcMap := template.FuncMap{

"static": func(path string) string {

return "/" + hashFS.HashName("static/"+path)

},

}

// ...

}

Although Go’s http.FileServer supports Last-Modified headers, unfortunately go:embed doesn’t provide file modification time. Nor does it support ETag.

That’s a bit annoying, and I was just about to write an ETag wrapper myself, but then I found a 200-line library by Ben Johnson (who works at Fly.io!) called hashfs. The library wraps an fs.FS filesystem and gives you an http.Handler that generates ETag headers, allowing browsers to cache effectively.

Background jobs

Before switching to Fly.io, I had two cron jobs:

- A job that sends “post-wedding” emails to customers a few days after their wedding date passes.

- A job that backs up the database daily using the SQLite client’s

.backupcommand, and uploads the result to an S3 bucket.

Fly.io doesn’t support cron jobs as a built-in concept, so I had a few options to choose from:

- Use Fly.io to run a service manager that would start Gifty as well as the cron jobs. [Update: as Ben Johnson pointed out, if I was using a Dockerfile, I could

apt install cronand then just use cron normally.] - Fire up a separate cron application in Fly.io or use Fly Machines.

- Use simple goroutines in the Go server to perform background tasks.

Option 1 would defeat some of the simplicity of using Fly.io in the first place: I’d have to create a Dockerfile and configure various things, which I wanted to avoid.

Option 2 is cleaner, but it might be annoying to connect the cron app to the main app to access the database (are volumes cross-application? I’m not sure). And Fly Machines is another thing to learn (and what would start them on a time interval?).

Option 3 at first seems dirty, but I love the simplicity of it! I wouldn’t have to learn anything new, and I knew I wasn’t going to run more than one instance of my app, so I ended up going with that.

In Go, you can start a timed background task in a few lines of code using a goroutine and a time.Ticker. This is roughly what I’m doing (in main):

// Start goroutine to send post-wedding emails every so often.

go func() {

ticker := time.NewTicker(time.Hour)

for {

<-ticker.C

err := sendPostWeddingEmails(config, emailRenderer, dbModel)

if err != nil {

emailAdmin("error sending post-wedding email: %v", err)

}

}

}()

// Start goroutine to check if database needs backing up every so often.

// Ticks every 6 hours, but backUpDatabase skips if there's already one today.

go func() {

ticker := time.NewTicker(6 * time.Hour)

for {

<-ticker.C

err := backUpDatabase(config, s3Client)

if err != nil {

emailAdmin("error backing up database: %v", err)

}

}

}()

It’s simplistic, but it works nicely. Retries are not handled directly – I just use the fact that it’ll try again next tick (not that I get many errors!).

And yes, I know – the goroutines aren’t gracefully shut down when the server stops. But in the unlikely event the server exits when a task is running, it won’t hurt anything. The one additional thing I do in the real code is catch panics and email those to me too.

The backUpDatabase function (again, keeping it stupid-simple) uses os/exec to run the sqlite3 client with a script of .backup <filename> and then uploads the result to a private S3 bucket. It also deletes any backups older than the latest 10.

Load testing

I already took down the old EC2 server, so unfortunately I can’t compare before and after times. However, I mainly wanted to test that the new server was fast enough.

The site on Fly.io feels faster from here (New Zealand), but I think that’s mainly because I’m hosting it in Fly.io’s syd region (in Sydney, just across the ditch), whereas previously it was hosted in AWS’s us-west-2 region (in Oregon), which is significantly further from me and most of my customers.

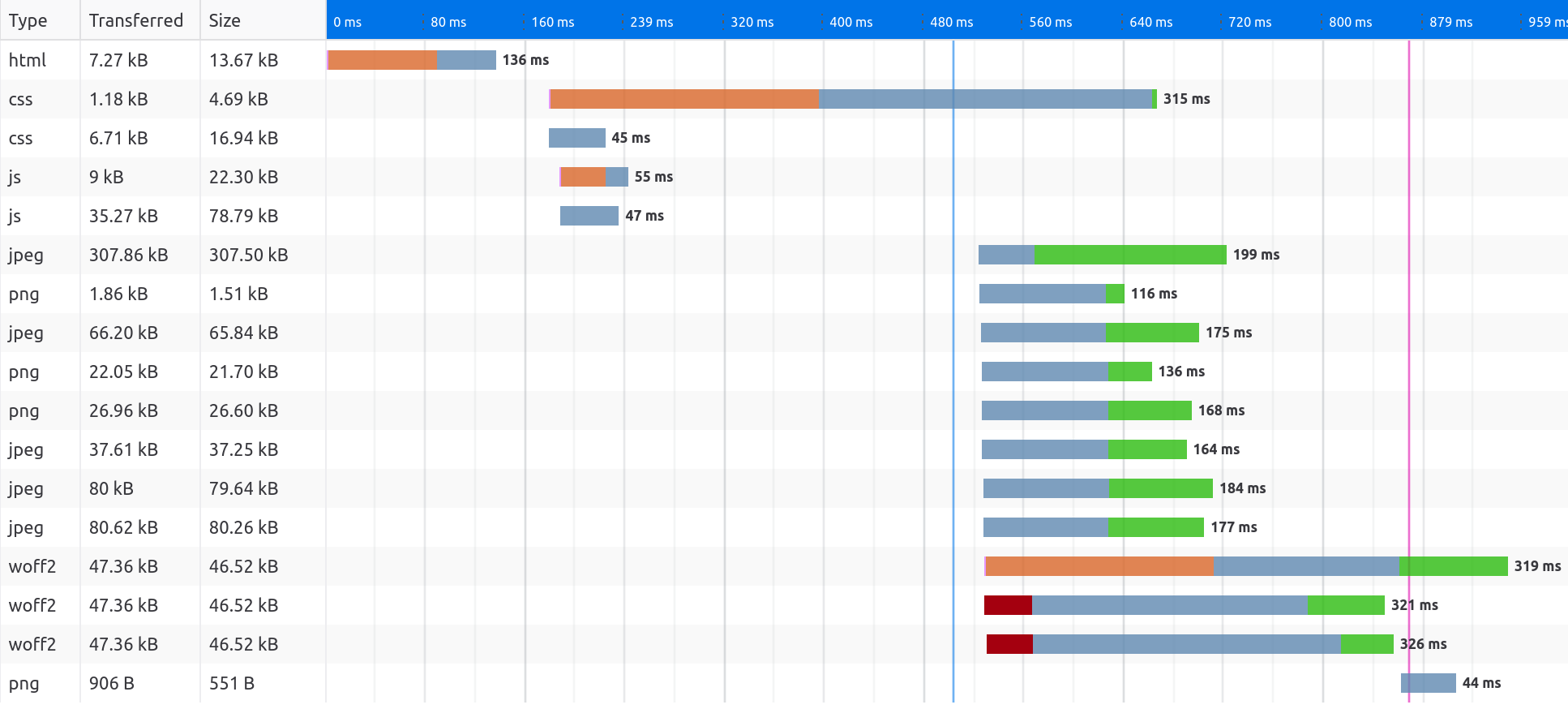

In addition, my static files are now hosted on the same domain and server, which means they’re also coming from Sydney instead of the U.S., and means the browser may be able to reuse open connections, and doesn’t have to do TLS setup for another host.

Here’s a screenshot of the network timeline for the initial HTML and subsequent static files – uncached. This is from the homepage, which is the heaviest page as it includes a number of images, but I’m proud of the fact that it totals less than 900KB and is fully loaded in under a second.

I ran a small test using the HTTP load testing tool Vegeta hitting four URLs: three pages that render HTML templates (the home page, a registry page which does two SQL queries, and the contact page), and a medium-sized image.

I had the “attack” run for 10 seconds. The default rate is 50 requests per second, but I also tried 500 and 1000. Below are the results:

$ cat urls.txt | vegeta attack -duration=10s | vegeta report

Requests [total, rate, throughput] 500, 50.10, 49.84

Duration [total, attack, wait] 10.032s, 9.98s, 51.434ms

Latencies [min, mean, 50, 90, 95, 99, max] 42.805ms, 50.004ms, 45.411ms, 53.643ms, 58.801ms, 146.6ms, 216.559ms

Bytes In [total, mean] 10757125, 21514.25

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 100.00%

Status Codes [code:count] 200:500

Error Set:

$ cat urls.txt | vegeta attack -duration=10s -rate=500/s | vegeta report

Requests [total, rate, throughput] 5000, 500.08, 497.69

Duration [total, attack, wait] 10.046s, 9.998s, 47.869ms

Latencies [min, mean, 50, 90, 95, 99, max] 42.615ms, 61.354ms, 49.472ms, 72.032ms, 117.76ms, 304.653ms, 1.177s

Bytes In [total, mean] 107571250, 21514.25

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 100.00%

Status Codes [code:count] 200:5000

Error Set:

$ cat urls.txt | vegeta attack -duration=10s -rate=1000/s | vegeta report

Requests [total, rate, throughput] 10000, 1000.11, 994.86

Duration [total, attack, wait] 10.05s, 9.999s, 50.801ms

Latencies [min, mean, 50, 90, 95, 99, max] 42.876ms, 126.907ms, 60.591ms, 254.24ms, 419.47ms, 1.294s, 3.508s

Bytes In [total, mean] 215062995, 21506.30

Bytes Out [total, mean] 0, 0.00

Success [ratio] 99.98%

Status Codes [code:count] 0:2 200:9998

Error Set:

Get "https://giftyweddings.com/": ... connection reset by peer

Get "https://giftyweddings.com/static/images/gifts-b80...38f.jpg": ... connection reset by peer

Even when I went up to the rate of 500 requests per second it handled fine, and browsing the site was still fast, though the mean went up from 50ms to 61ms and the 99th percentile from 147ms to 305ms.

It was only went I cranked the rate up to 1000 requests per second that the Fly.io VM started to struggle: the mean went up to 127ms and the p99 to 1.3s, there were two errors out of 10,000 requests, and browsing the site during the test felt sluggish.

So the smallest shared 1 CPU Fly.io VM can handle 500 requests per second without any problems. I’m happy with that! I realize this is not exactly a scientific test, but it’s good enough for my purposes here.

Conclusion

I’m only a few weeks into using Fly.io to host my side projects, but I’m very happy with their product so far. I was quite happy to delete the 500 lines of Ansible scripts, systemd unit files, and Caddy config files.

It also made me smile to finally stop the EC2 instance and bump my AWS bill down from $9 per month to about 10 cents per month (I still use S3 for user-uploaded images and for backups). I have nothing against EC2 and would use it again for certain things, but for small web applications, Fly.io seems like a great fit.

It probably sounds like Fly.io is paying me to carry on like this, but trust me, they’re not. I’m just an enthusiastic geek who likes their product, their support for very small VMs, and their love of SQLite. Not to mention their pricing!

For discussion, see Hacker News and r/golang.

I’d love it if you sponsored me on GitHub – it will motivate me to work on my open source projects and write more good content. Thanks!