GoAWK, an AWK interpreter written in Go

November 2018

Summary: After reading The AWK Programming Language I was inspired to write an interpreter for AWK in Go. This article gives an overview of AWK, describes how GoAWK works, how I approached testing, and how I measured and improved its performance.

Go to: Overview of AWK | Code walkthrough | Testing | Performance

Chinese (zh) translation: 一个用Go编写的AWK解释器

Update: GoAWK now uses a bytecode compiler and includes native support for CSV files.

AWK is a fascinating text processing language, and The AWK Programming Language is a wonderfully concise book describing it. The A, W, and K in AWK stand for the surnames of the three original creators: Alfred Aho, Peter Weinberger, and Brian Kernighan. Kernighan is also an author of The C Programming Language (“K&R”), and the two books have that same each-page-packs-a-punch feel.

AWK was released in 1977, which makes it over 40 years old! Not bad for a domain-specific language that’s still used for one-liners on Unix command lines everywhere.

I was still on a bit of an “interpreter high” after implementing a little language of my own as well as Bob Nystrom’s Lox language in Lox. After reading the AWK book I thought it’d be fun (for some nerdy value of “fun”) to write an interpreter for it in Go. How hard could it be?

As it turns out, not too hard to get it working at a basic level, but a bit tricky to get the correct POSIX AWK semantics and to make it fast.

First, a brief intro to the AWK language (skip to the next section if you already know it).

Overview of AWK

If you’re not familiar with AWK, here’s a one-sentence summary: AWK reads a text file line by line, and for each line that matches a pattern expression, it executes an action (which normally prints output).

So given an example input file (a web server log file) where each line uses the format "timestamp method path ip status time" :

2018-11-07T07:56:34Z GET /about 1.2.3.4 200 0.013

2018-11-07T07:56:35Z GET /contact 1.2.3.4 200 0.020

2018-11-07T07:56:37Z POST /contact 1.2.3.4 200 1.309

2018-11-07T07:56:40Z GET /robots.txt 123.0.0.1 404 0.004

2018-11-07T07:57:00Z GET /about 2.3.4.5 200 0.014

2018-11-07T08:00:00Z GET /asdf 3.4.5.6 404 0.005

2018-11-07T08:00:01Z GET /fdsa 3.4.5.6 404 0.004

2018-11-07T08:00:02Z HEAD / 4.5.6.7 200 0.008

2018-11-07T08:00:15Z GET / 4.5.6.7 200 0.055

2018-11-07T08:05:57Z GET /robots.txt 201.12.34.56 404 0.004

2018-11-07T08:05:58Z HEAD / 5.6.7.8 200 0.007

2018-11-07T08:05:59Z GET / 5.6.7.8 200 0.049

If we want to see the IP addresses (field 4) of all hits to the “about” page, we could write:

$ awk '/about/ { print $4 }' server.log

1.2.3.4

2.3.4.5

The pattern above is the slash-delimited regex /about/, and the action is to print the fourth field ($4). By default, AWK splits the line into fields on whitespace, but the field separator is easily configurable, and can be a regex.

Normally a regex pattern matches the entire line, but you can match on an arbitrary expression too. The above would match URL /not-about too, but you can tighten it up to test that the path (field 3) is exactly "/about":

$ awk '$3 == "/about" { print $4 }' server.log

1.2.3.4

2.3.4.5

If we want to determine the average response time (field 6) of all GET requests, we could sum the response time and count the number of GET requests, then print the average in the END block – 18 milliseconds, not bad:

$ awk '/GET/ { total += $6; n++ } END { print total/n }' server.log

0.0186667

AWK supports hash tables (called “associative arrays”), so you can print the count of each request method like so – notice the pattern is optional, and omitted here:

$ awk '{ num[$2]++ } END { for (m in num) print m, num[m] }' server.log

GET 9

POST 1

HEAD 2

AWK has two scalar types, string and number, but it’s been described as “stringly typed”, because the comparison operators like == and < do numeric comparisons if the data comes from user input and parses as a number, otherwise they do string comparisons. This sounds sloppy, but for text processing it’s usually what you want.

The language supports the usual range of C-like expressions and control structures (if, for, etc). It also has a range of builtin functions like substr() and tolower(), and it supports user-defined functions complete with local variables and array parameters.

So it’s most definitely Turing-complete, and is actually quite a nice, powerful language. You can even generate the Mandelbrot set in a couple dozen lines of code:

$ awk -v width=150 -v height=50 -f testdata/tt.x1_mandelbrot

......................................................................................................................................................

............................................................................................................-.........................................

.....................................................................................................----++-*------...................................

...................................................................................................--------$+---------................................

................................................................................................-----------++$++--+++---..............................

..............................................................................................--------------++*%#+++------............................

............................................................................................--------------++%*%@*++----------.........................

.........................................................................................------------++**++*# *++++%----------.....................

......................................................................................--------------+++ %#%+-------------.................

..................................................................................-------------------+* @ %*+------------------.............

.............................................................................---------------------+++++ +++--------------------..........

........................................................................----------*%+**#@++++++$ %++****%% $%**+**+++#++---------+*+---........

.................................................................-----------------+*$% $ # ++* $ # *++++#*+++**++----......

..........................................................------------------------+++@ # @**# @ *#+-----.....

....................................................-----------------------------++++*# %*+-------....

...............................................------------------------------+$+*%**# %*++--------....

..........................................---+-------------------------------++ %#+---------...

......................................--------+ +----------++---------------++**%$ *%*+* ----...

..................................------------+*+++++*+++++ *++++++-----+++++$@ +----...

...............................----------------+++#% $$**%* @ $**#%+++++++++ %++------...

............................------------------+++*%$ $ *++++* # **-----...

..........................-------------------+*+**# @%**% #$+------...

.......................---------------%++++++++*# ## $+------...

....................-----------------+++#**%***# *--------...

.......-----------++--------------++++**%$ +----------...

...... %*++-----------...

.......-----------++--------------++++**%$ +----------...

....................-----------------+++#**%***# *--------...

.......................---------------%++++++++*# ## $+------...

..........................-------------------+*+**# @%**% #$+------...

............................------------------+++*%$ $ *++++* # **-----...

...............................----------------+++#% $$**%* @ $**#%+++++++++ %++------...

..................................------------+*+++++*+++++ *++++++-----+++++$@ +----...

......................................--------+ +----------++---------------++**%$ *%*+* ----...

..........................................---+-------------------------------++ %#+---------...

...............................................------------------------------+$+*%**# %*++--------....

....................................................-----------------------------++++*# %*+-------....

..........................................................------------------------+++@ # @**# @ *#+-----.....

.................................................................-----------------+*$% $ # ++* $ # *++++#*+++**++----......

........................................................................----------*%+**#@++++++$ %++****%% $%**+**+++#++---------+*+---........

.............................................................................---------------------+++++ +++--------------------..........

..................................................................................-------------------+* @ %*+------------------.............

......................................................................................--------------+++ %#%+-------------.................

.........................................................................................------------++**++*# *++++%----------.....................

............................................................................................--------------++%*%@*++----------.........................

..............................................................................................--------------++*%#+++------............................

................................................................................................-----------++$++--+++---..............................

...................................................................................................--------$+---------................................

.....................................................................................................----++-*------...................................

............................................................................................................-.........................................And that’s AWK in a very small nutshell.

Code walkthrough

GoAWK is not ground-breaking in terms of compiler design. It’s made up of a lexer, parser, resolver, interpreter, and main program (GitHub repo). Only packages from the Go standard library were used in the making of this program.

Lexer

It all starts with the lexer, which converts AWK source code into a stream of tokens. The guts of the lexer is the scan() method, which skips whitespace and comments, then parses the next token: for example, DOLLAR, NUMBER, or LPAREN. Each token is returned with its source code position (line and column) so the parser can include this information in syntax error messages.

The bulk of the code (in the Lexer.scan method) is just a big switch statement that switches on the token’s first character. Here’s a snippet:

// ...

switch ch {

case '$':

tok = DOLLAR

case '0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9', '.':

start := l.offset - 2

gotDigit := false

if ch != '.' {

gotDigit = true

for l.ch >= '0' && l.ch <= '9' {

l.next()

}

if l.ch == '.' {

l.next()

}

}

// ...

tok = NUMBER

case '{':

tok = LBRACE

case '}':

tok = RBRACE

case '=':

tok = l.choice('=', ASSIGN, EQUALS)

// ...

One of the quirky things about AWK grammar is that parsing / and /regex/ is ambiguous – you have to know the parsing context to know whether to return a DIV or a REGEX token. So the lexer exposes a Scan method for normal tokens and a ScanRegex method for the parser to call where it expects a regex token.

Parser

Next is the parser, a fairly standard recursive-descent parser that creates an abstract syntax tree (AST). I didn’t fancy learning how to drive a parser generator like yacc or bringing in an external dependency, so GoAWK’s parser is hand-rolled with love.

The AST nodes are simple Go structs, with Expr and Stmt as interfaces that are implemented by each expression and statement struct, respectively. The AST nodes can also pretty-print themselves by calling the String() method – this was very useful for debugging the parser, and you can enable it by specifying -d on the command line:

$ goawk -d 'BEGIN { x=4; print x+3; }'

BEGIN {

x = 4

print (x + 3)

}

7

The AWK grammar is a bit quirky in places, not the least of which is that expressions in print statements don’t support > or | except inside parentheses. This is supposed to make redirecting or piping output simpler.

print x > ymeans print variablexredirected to a file with nameyprint (x > y)means print boolean true (1) ifxis greater thany

I couldn’t figure out a better way to do this than two paths down the recursive-descent tree – expr() and printExpr() in the code:

func (p *parser) expr() Expr { return p.getLine() }

func (p *parser) printExpr() Expr { return p._assign(p.printCond) }

Builtin function calls are parsed specially, so that the number of arguments (and in some cases the types) can be checked at parse time. For example, parsing match(str, regex):

case F_MATCH:

p.next()

p.expect(LPAREN)

str := p.expr()

p.commaNewlines()

regex := p.regexStr(p.expr)

p.expect(RPAREN)

return &CallExpr{F_MATCH, []Expr{str, regex}}

A lot of parsing functions flag an error on invalid syntax or an unexpected token. It makes life easier to not check these errors at every step, but rather panic with a special ParseError type which is recovered at the top level. This avoids a ton of repetitive error handling in the recursive descent code. Here’s how the top-level ParseProgram function does that:

func ParseProgram(src []byte, config *ParserConfig) (

prog *Program, err error) {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

// Convert to ParseError or re-panic

err = r.(*ParseError)

}

}()

// ...

}

Resolver

The resolver is actually part of the parser package. It does basic type checking of arrays versus scalars, and assigns integer indexes to all variable references (to avoid slower map lookups at execution time).

I think the way I’ve done the resolver is non-traditional: instead of making a full pass over the AST, the parser records just what’s necessary for the resolver to figure out the types (a list of function calls and variable references). This is probably faster than walking the whole tree, but it makes the code a bit less straight-forward.

In fact, the resolver was one of the harder pieces of code I’ve written for a while. It’s the one piece of the GoAWK source I’m not particularly happy with. It works, but it’s messy, and I’m still not sure I’ve covered all the edge cases.

The complexity comes from the fact that when calling functions, you don’t know whether an argument is a scalar or an array at the call site. You have to peruse the types in the called function (and maybe in the functions it calls) to determine that. Consider this AWK program:

function g(b, y) { return f(b, y) }

function f(a, x) { return a[x] }

BEGIN { c[1]=2; print f(c, 1); print g(c, 1) }

The program simply prints 2 twice. But when we’re calling f inside g we don’t know the types of the arguments yet. It’s part of the resolver’s job to figure this out in an iterative fashion. (See resolveVars in resolve.go.)

After figuring out the unknown arguments types, the resolver assign integer indexes to all variable references, global and local.

Interpreter

Update: As of v1.15.0, GoAWK uses a faster bytecode compiler and virtual machine instead of a tree-walking interpreter.

The interpreter is a simple tree-walk interpreter. The interpreter implements statement execution and expression evaluation, input/output, function calls, and the base value type.

Statement execution starts in interp.go with ExecProgram, which takes a parsed Program, sets up the interpreter, and then executes BEGIN blocks, patterns and actions, and END blocks. Executing the actions includes evaluating pattern expressions and determining if they match the current line. This includes “range patterns” like NR==4, NR==10, which matches lines between the start and the stop pattern.

A statement is executed by the execute method, which takes a Stmt of any type, performs a big type switch on it to determine what kind of statement it is, and executes the behavior of that statement.

Expression evaluation works the same way, except it happens in the eval method, which takes an Expr and switches on the expression type.

Most binary expressions (apart from the short-circuiting && and ||) are evaluated via evalBinary, which contains a further switch on the operator token, like so:

func (p *interp) evalBinary(op Token, l, r value) (value, error) {

switch op {

case ADD:

return num(l.num() + r.num()), nil

case SUB:

return num(l.num() - r.num()), nil

case EQUALS:

if l.isTrueStr() || r.isTrueStr() {

return boolean(p.toString(l) == p.toString(r)), nil

} else {

return boolean(l.n == r.n), nil

}

// ...

}

In the EQUALS case you can see the “stringly typed” nature of AWK: if either operand is definitely a “true string” (not a numeric string from user input), do a string comparison, otherwise do a numeric comparison. This means a comparison like $3 == "foo" does a string comparison, but $3 == 3.14 does a numeric one, which is what you’d expect.

AWK’s associative arrays map very well to a Go map[string]value type, so that makes implementing those easy. Speaking of which, Go’s garbage collector means we don’t have to worry about writing our own GC.

Input and output is handled in io.go. All I/O is buffered for efficiency, and we use Go’s bufio.Scanner to read input records and bufio.Writer to buffer output.

Input records are usually lines (Scanner’s default behavior), but the record separator RS can also be set to another character to split on, or to empty string, which means split on two consecutive newlines (a blank line) for handling multiline records. These methods still use bufio.Scanner, but with a custom split function, for example:

// Splitter function that splits records on the given separator byte

type byteSplitter struct {

sep byte

}

func (s byteSplitter) scan(data []byte, atEOF bool)

(advance int, token []byte, err error) {

if atEOF && len(data) == 0 {

return 0, nil, nil

}

if i := bytes.IndexByte(data, s.sep); i >= 0 {

// We have a full sep-terminated record

return i + 1, data[0:i], nil

}

// If at EOF, we have a final, non-terminated record; return it

if atEOF {

return len(data), data, nil

}

// Request more data

return 0, nil, nil

}

Output from print or printf can be redirected to a file, appended to a file, or piped to a command: this is handled in getOutputStream. Input can come from stdin, a file, or be pipe from a command.

Functions are implemented in functions.go, including builtin, user-defined, and native (Go-defined) functions.

The callBuiltin method again uses a large switch statement to determine the AWK function we’re calling, for example split() or sqrt(). The builtin split requires special handling because it takes a non-evaluated array parameter. Similarly sub and gsub actually take an “lvalue” parameter that’s assigned to. For the rest of the functions, we evaluate the arguments first and perform the operation.

Most of the functions are implemented using parts of Go’s standard library. For example, all the math functions like sqrt() use the standard math package, split() uses strings and regexp functions. GoAWK re-uses Go’s regular expressions, so obscure regex syntax might not behave identically to the “one true awk”.

Speaking of regexes, I cache compilation of regexes using a simple bounded cache, which is enough to speed up almost all AWK scripts:

// Compile regex string (or fetch from regex cache)

func (p *interp) compileRegex(regex string) (*regexp.Regexp, error) {

if re, ok := p.regexCache[regex]; ok {

return re, nil

}

re, err := regexp.Compile(regex)

if err != nil {

return nil, newError("invalid regex %q: %s", regex, err)

}

// Dumb, non-LRU cache: just cache the first N regexes

if len(p.regexCache) < maxCachedRegexes {

p.regexCache[regex] = re

}

return re, nil

}

I also cheat with AWK’s printf statement, converting the AWK format string and types into Go types so I can re-use Go’s fmt.Sprintf function. Again, this format string conversion is cached.

User-defined calls use callUser, which evaluates the function’s arguments and pushes them onto the locals stack. This is somewhat more complicated than you’d think for two reasons: first, you can pass arrays as arguments (by reference), and second, you can call a function with fewer arguments than it has parameters.

It also checks the call depth (currently maximum 1000), to avoid a panic in case of unbounded recursion.

In GoAWK v1.1.0, I added support for calling native Go functions via the Funcs field in the parser and interpreter config structs. If you’re using GoAWK in your Go programs you can make use of Go-defined functions to do fancy things like make an HTTP request. This is done via callNative, which uses the Go reflect package to convert the arguments and return value (only scalar types are supported).

Values are implemented in value.go. GoAWK values are strings or numbers (or “numeric strings”) and use the value struct, which is passed by value, and is defined as follows:

type value struct {

typ valueType // Value type (nil, str, or num)

isNumStr bool // True if str value is a "numeric string"

s string // String value (typeStr)

n float64 // Numeric value (typeNum and numeric strings)

}

Originally I had made the GoAWK value type an interface{} which held string and float64. But you couldn’t tell the difference between regular strings and numeric strings, so decided to go with a struct. And my hunch is that it’s better to pass a small 4-word struct by value than by pointer, so that’s what I did (though I haven’t verified that).

To detect “numeric strings” (see numStr), we simply trim spaces and use Go’s strconv.ParseFloat function. However, when string values are being explicitly converted to numbers in value.num(), I had to roll my own parsing function because those conversions allow things like "1.5foo", whereas ParseFloat doesn’t.

Main

The main program in goawk.go rolls all of the above together into the command-line utility goawk. Again, nothing fancy here – it even uses the standard Go flag package for parsing command-line arguments.

The goawk utility has a little helper function, showSourceLine, which shows the error line and position of syntax errors. For example:

$ goawk 'BEGIN { print sqrt(2; }'

--------------------------------------------

BEGIN { print sqrt(2; }

^

--------------------------------------------

parse error at 1:21: expected ) instead of ;

There’s nothing special about goawk: it just calls the parser and interp packages. GoAWK has a pretty simple Go API, so check out the GoDoc API documentation if you want to call it from your own Go programs.

How I tested it

Lexer tests

The lexer tests use table-driven tests, comparing source input to a stringified version of the lexer output. This includes checking the token position (line:column) as well as the token’s string value (used for NAME, NUMBER, STRING, and REGEX tokens):

func TestLexer(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

input string

output string

}{

// Names and keywords

{"x", `1:1 name "x"`},

{"x y0", `1:1 name "x", 1:3 name "y0"`},

{"x 0y", `1:1 name "x", 1:3 number "0", 1:4 name "y"`},

{"sub SUB", `1:1 sub "", 1:5 name "SUB"`},

// String tokens

{`"foo"`, `1:1 string "foo"`},

{`"a\t\r\n\z\'\"b"`, `1:1 string "a\t\r\nz'\"b"`},

// ...

}

// ...

}

Parser tests

The parser doesn’t really have explicit unit tests, except TestParseAndString which tests one big program with all of the syntax constructs in it – the test is simply that it parses and can be serialized again via pretty-printing. My intention here is to test the parsing logic in the interpreter tests.

Interpreter tests

The interpreter unit tests are another long list of table-driven tests. They’re a little more complicated than the lexer tests – they take the AWK source, expected input and expected output, and also an expected error string and AWK error string if the test is supposed to cause an error.

You can optionally run the interpreter tests against an external AWK intepreter by specifying a command-line like go test ./interp -awk=gawk. I’ve ensured it works against both awk and gawk – the error messages are quite different between the two, and I’ve tried to account for that by testing against just a substring of the error message.

Sometimes awk and gawk have known different behaviour, or don’t catch quite the same errors as GoAWK, so in a few of the tests I have to exclude an interpreter by name – this is done using a special !awk (“not awk”) comment in the source string.

Here’s what the interpreter unit tests look like:

func TestInterp(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

src string

in string

out string

err string // error from GoAWK must equal this

awkErr string // error from awk/gawk must contain this

}{

{`$0`, "foo\n\nbar", "foo\nbar\n", "", ""},

{`{ print $0 }`, "foo\n\nbar", "foo\n\nbar\n", "", ""},

{`$1=="foo"`, "foo\n\nbar", "foo\n", "", ""},

{`$1==42`, "foo\n42\nbar", "42\n", "", ""},

{`$1=="42"`, "foo\n42\nbar", "42\n", "", ""},

{`BEGIN { printf "%d" }`, "", "",

"format error: got 0 args, expected 1", "not enough arg"},

// ...

}

// ...

}

Command line tests

I also wanted to test the goawk command-line handling, so in goawk_test.go there’s another set of table-driven tests that test things like -f, -v, ARGV, and other things related to the command line:

func TestCommandLine(t *testing.T) {

tests := []struct {

args []string

stdin string

output string

}{

{[]string{"-f", "-"}, `BEGIN { print "b" }`, "b\n"},

{[]string{"-f", "-", "-f", "-"}, `BEGIN { print "b" }`, "b\n"},

{[]string{`BEGIN { print "a" }`}, "", "a\n"},

{[]string{`$0`}, "one\n\nthree", "one\nthree\n"},

{[]string{`$0`, "-"}, "one\n\nthree", "one\nthree\n"},

{[]string{`$0`, "-", "-"}, "one\n\nthree", "one\nthree\n"},

// ...

}

// ...

}

These are tested against the goawk binary as well as an external AWK program (which defaults to gawk).

AWK test suite

I also test GoAWK against Brian Kernighan’s “one true awk” test suite, which are the p.* and t.* files in the testdata directory. The TestAWK function in goawk_test.go drives these tests. The output from the test programs is compared against the output from an external AWK program (again defaulting to gawk) to ensure it matches.

A few test programs, for example those that call rand() can’t really be diff’d against AWK, so I exclude those. And for other programs, for example those that loop through an array (where iteration order is undefined), I sort the lines in the output before the diff.

More recently I added much of the GNU Awk test suite as well. This is tested via TestGAWK, with the test files in testdata/gawk. I’ve included all the tests that test POSIX functionality (not gawk extensions). There are a handful of failing tests that are currently skipped, but these are things that shouldn’t crop up in real code (for example, GoAWK doesn’t parse $$a++++ correctly).

Fuzz testing

One last type of testing I used is “fuzz testing”. This is a method of sending randomized inputs to the interpreter until it breaks. I caught several crashes (panics) this way, and even one bug in the Go compiler which caused an out-of-bounds slice access to segfault (though I found that had already been fixed in Go 1.11).

To drive the fuzzing, I simply used the go-fuzz library with a Fuzz function:

func Fuzz(data []byte) int {

input := bytes.NewReader([]byte("foo bar\nbaz buz\n"))

err := interp.Exec(string(data), " ", input, &bytes.Buffer{})

if err != nil {

return 0

}

return 1

}

Fuzz testing found a number of bugs and edge cases I hadn’t caught with the other methods of testing. Mostly these were things you wouldn’t write in real code, but it’s nice to have a tireless robot help you add a layer of robustness. In GoAWK, fuzz testing found at least these issues:

- c59731f: Fix panic with using built-in (scalar) in array context

- 59c931f: Fix crashes when trying to read from output stream (and vice versa)

- b09e51f: Disallow setting NF and $n past 1,000,000 (fuzzer found this)

- 6d99151: Fix ‘value out of range’ panic when converting to float (go-fuzz found this)

See fuzz/README.txt for details on how to run the fuzzer.

Improving performance

Skip the discussion, jump to the numbers!

Performance issues tend to be caused by bottlenecks in the following areas, from most to least impactful (thanks to Alan Donovan for this succinct way of thinking about it):

- Input/output

- Memory allocations

- CPU cycles

If you’re doing too many I/O or system calls, that’s going to be a huge hit.

Memory allocations are next: they’re costly, and one of the key things Go gives a good amount of control over is memory allocation (for example, the “cap” argument to make()).

Finally comes CPU cycles – this is often the least impactful, though it’s sometimes the only thing people think of when we talk about “performance”.

In GoAWK, I’ve done some optimization in all three areas. The biggest wins to be had for typical AWK programs were related to I/O – as expected, because AWK programs normally read input, process it a bit, and write output. But there were some important gains to be had in the allocation and CPU departments too.

How I profiled

Where the bottlenecks are is often unintuitive, so measurement is key. Let’s look at how you measure what’s going on in your Go code.

It’s fairly easy to instrument code for profiling using the standard library runtime/pprof package. (You can read more about profiling Go programs here.)

First I added a -cpuprofile command line flag, and if that’s set, enable CPU profiling. Here’s what that looks like in code:

if *cpuprofile != "" {

f, err := os.Create(*cpuprofile)

if err != nil {

errorExit("could not create CPU profile: %v", err)

}

if err := pprof.StartCPUProfile(f); err != nil {

errorExit("could not start CPU profile: %v", err)

}

}

// ... run interp.Exec ...

if *cpuprofile != "" {

pprof.StopCPUProfile()

}

Then you can run the AWK program you want to profile:

$ ./goawk -cpuprofile=prof 'BEGIN { for (i=0; i<100000000; i++) s++ }'

And finally use the pprof tool to view the output (the -http flag fires up a tab in your web browser with a couple of nice ways to view the data):

$ go tool pprof -http=:4001 prof

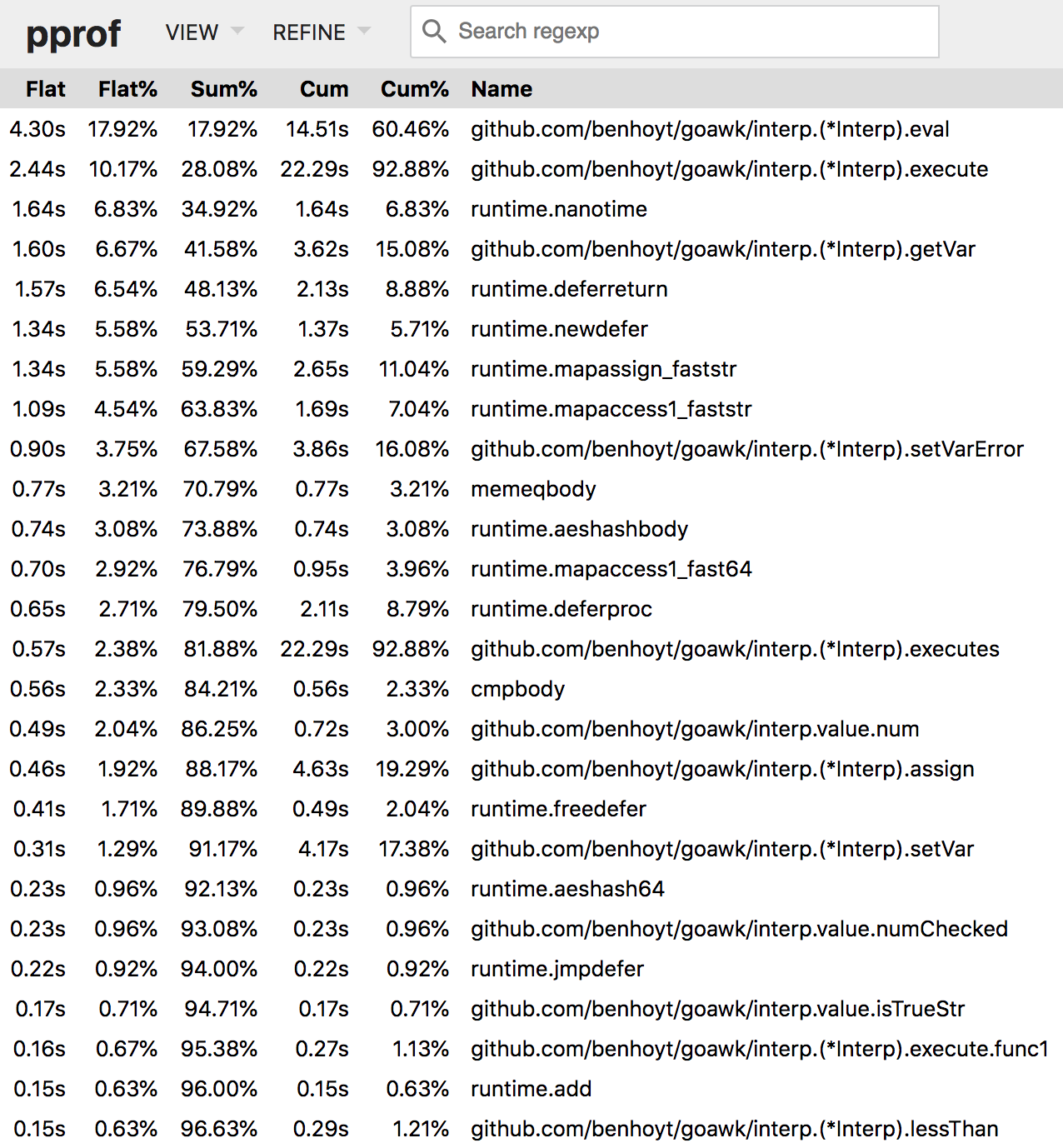

Here’s a screenshot of the “top” view, which I found most helpful:

From this screenshot you can see a couple of things immediately:

- Variable access via maps is slowing us down (

getVar,mapassign,mapaccess) - The

panic-based error handling is rather slow (all thedeferlines)

Both of these I’ve addressed as described below. I ran the profiler many more times on different kinds of AWK programs, and found a number of issues, starting with I/O.

The performance improvements

Sure enough, GoAWK had I/O issues – I wasn’t buffering writes to stdout. So microbenchmarks looked okay, but real AWK programs ran many times slower than necessary. So speeding up output was one of the first optimizations I made (and later I realized I’d forgotten to do this for redirected output too):

- 60745c3: Buffer stdout (and stderr) for 10x speedup

- 6ba004f: Buffer redirected output for performance

Next I changed to using switch/case for binary operations instead of looking up the function in a map and calling it. It’s not obvious this will be faster, particularly as switch in Go jumps down through the list of cases and doesn’t use “computed gotos”. But I guess the constant factors involved in calling a function outweigh that in many cases:

- ad8ff0e: Speed up binary ops by moving from map to switch/case

benchmark old ns/op new ns/op delta

BenchmarkComparisons-8 975 739 -24.21%

BenchmarkBinaryOperators-8 1294 993 -23.26%

BenchmarkConcatSmall-8 1312 1120 -14.63%

BenchmarkArrayOperations-8 2542 2350 -7.55%

BenchmarkRecursiveFunc-8 64319 60507 -5.93%

BenchmarkBuiltinSub-8 16213 15305 -5.60%

BenchmarkForInLoop-8 3886 4092 +5.30%

...

Interestingly, some of my improvements slowed down completely unrelated code paths. I still don’t really know why. Is it measurement noise? I don’t think so, because it seems quite consistent. My guess is that it’s the fact that the machine code has been rearranged and somehow causes cache misses or branch prediction changes in other parts of the code.

The next big change was to resolve variable names to indexes at parse time. Previously I was doing all variable lookups in a map[string]value at runtime, but variable references in AWK can be resolved at parse time, and then the interpreter can look them up in a []value instead. It also avoids allocations in some cases as variables are assigned as the map grows:

- e0d7287: Big perf improvements: resolve variables at parse time

benchmark old ns/op new ns/op delta

BenchmarkFuncCall-8 13710 5313 -61.25%

BenchmarkRecursiveFunc-8 60507 30719 -49.23%

BenchmarkForInLoop-8 4092 2467 -39.71%

BenchmarkLocalVars-8 2959 1827 -38.26%

BenchmarkForLoop-8 15706 10349 -34.11%

BenchmarkIncrDecr-8 2441 1647 -32.53%

BenchmarkGlobalVars-8 2628 1812 -31.05%

...

Initially I had interp.eval() return just the value and panic with a special error on runtime error, but that was a significant slow-down, so I switched to using more verbose but more Go-like error return values. This would be a lot nicer with the proposed check keyword, but oh well. This change gave a 2-3x improvement on a lot of benchmarks:

- aa6aa75: Improve interp performance by removing panic/recover

benchmark old ns/op new ns/op delta

BenchmarkIfStatement-8 885 292 -67.01%

BenchmarkGlobalVars-8 1812 672 -62.91%

BenchmarkLocalVars-8 1827 682 -62.67%

BenchmarkIncrDecr-8 1647 714 -56.65%

BenchmarkCondExpr-8 604 280 -53.64%

BenchmarkForLoop-8 10349 6007 -41.96%

BenchmarkBuiltinLength-8 2775 1616 -41.77%

...

The next improvement was a couple of small but effective tweaks to evalIndex, which evaluates a slice of array expressions to produce a key string. In AWK, arrays can be indexed by multiple subscripts like a[1, 2], which actually just mashes them together into the string "1{SUBSEP}2" (the subscript separator defaults to \x1c).

But most of the time you only have a single subscript, so I optimized the common case. And for the multiple-subscript case, I did an initial allocation – hopefully on the stack – with make([]string, 0, 3) to avoid heap allocation for up to three subscripts.

- af99309: Speed up array operations

name old time/op new time/op delta

ArrayOperations-8 1.80µs ± 1% 1.13µs ± 1% -37.52%

Another case of reducing allocations was speeding up function calls by ensuring that calls with up to seven arguments don’t require heap allocations. This sped up calls to a number of builtins by 2x.

- e45e209: Speed up calls to builtin funcs by reducing allocations

name old time/op new time/op delta

BuiltinSubstr-8 3.11µs ± 0% 1.56µs ± 5% -49.77%

BuiltinIndex-8 3.00µs ± 2% 1.56µs ± 3% -48.17%

BuiltinLength-8 1.62µs ± 0% 0.93µs ± 6% -42.92%

ArrayOperations-8 1.80µs ± 1% 1.13µs ± 1% -37.12%

BuiltinMatch-8 3.77µs ± 1% 3.04µs ± 0% -19.39%

SimpleBuiltins-8 5.50µs ± 1% 4.68µs ± 0% -14.83%

BuiltinSprintf-8 14.3µs ± 4% 12.6µs ± 0% -12.50%

...

The next optimization was avoiding a heavyweight tool (text/scanner) for simply converting strings to numbers. I was using Scanner because it allows you to parse things like 1.23foo (AWK allows this when the string isn’t coming from user input), and strconv.ParseFloat doesn’t handle that.

I simply wrote my own lexing function to find the end of the actual floating-point number in the string, and call ParseFloat on that. This speeds up explicit string to number

conversions by more than 10x!

- 12b8520: Speed up string to number conversions by avoiding text/scanner

$ cat test.awk

BEGIN {

for (i=0; i<1000000; i++) {

"1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1";

"1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1"; "1.5e1"+"1";

}

}

$ time ./goawk_before test.awk

real 0m10.692s

$ time ./goawk_after test.awk

real 0m0.983s

One other thing I did was speed up the lexer by avoiding UTF-8 decoding during lexing. There’s no good reason not to keep everything as bytes, and it gave the lexer a 2-3x speed boost with these commits:

- 0fa32f9: Speed up lexer by avoiding UTF-8 decode

- 43af0cb: Speed up lexer more by changing from rune to byte type

- c5a32eb: Speed up lexer by reducing allocations

There are a few additional improvements I’ve made since then, most notably:

- 5cc26a7: Using a faster version of TrimSpace, which I hope is included in Go 1.13

- 2fe4d6a: Lazily splitting the line into fields only when a field or

NFis accessed (this is what makes thett.01benchmark 20x that of awk)

Performance numbers

So how does GoAWK compare to the other AWK implementations? Pretty well! In the following chart:

goawkrefers to GoAWK (v1.1.4)origrefers to the first “properly working” version of GoAWK, without optimizations (commit 8ab5446)awkis “one true awk” version 20121220 – the baselinegawkis GNU Awk version 4.2.1mawkis mawk version 1.3.4 (20171017)

The numbers below represent the speed of running the given test over 3 runs, relative to the speed of awk. So 6.27 means it was about 6x as fast as awk – higher is better. As you can see, GoAWK is significantly faster than awk in most cases and not too bad compared to gawk!

| Test | goawk | orig | awk | gawk | mawk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tt.01 (print) | 20.59 | 5.73 | 1.00 | 10.88 | 11.55 |

| tt.02 (print NR NF) | 5.46 | 4.69 | 1.00 | 3.63 | 4.98 |

| tt.02a (print length) | 4.39 | 3.81 | 1.00 | 2.98 | 4.49 |

| tt.03 (sum length) | 6.27 | 4.88 | 1.00 | 12.29 | 7.93 |

| tt.03a (sum field) | 6.57 | 3.06 | 1.00 | 16.07 | 7.75 |

| tt.04 (printf fields) | 1.34 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.53 | 2.82 |

| tt.05 (concat fields) | 1.68 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 3.37 |

| tt.06 (count lengths) | 5.66 | 3.99 | 1.00 | 8.21 | 7.45 |

| tt.07 (even fields) | 6.46 | 5.48 | 1.00 | 5.27 | 6.31 |

| tt.big (complex program) | 1.48 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 1.71 | 2.88 |

| tt.x1 (mandelbrot) | 1.05 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.52 | 2.03 |

| tt.x2 (sum loop) | 0.60 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 1.22 | 1.74 |

| Geo mean | 3.28 | 1.88 | 1.00 | 3.90 | 4.52 |

Where to from here?

I’d love to know if you use GoAWK, and please send bug reports and code feedback my way. If you don’t have a need for GoAWK, at least you’ve learned about AWK in general, and how useful a tool it is.

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed this LLM-free, hand-crafted article.

I’d love it if you sponsored me on GitHub – it will motivate me to work on my open source projects and write more good content. Thanks!