How our photo search engine really works

July 2011

Our recently-launched Oyster Shots is a new tool you can use to search all of our stunning hotel photos by keyword and hotel attributes (location, rating, and hotel type). So far we have about 300,000 published photos, so there’s a lot to search. Some examples to get you started: New York City Restaurants and Bars, Dominican Republic Beaches, and Luxury Hotel Bathrooms.

If you want to know how to use Oyster Shots, just go to the landing page and watch the “How does it work?” video on the left. But if you’re a techie and want to know how it really works under the hood, read on.

Tagging our photos

One of the main questions up-front was whether we’d take a full-text or a tagging approach. Full-text search sounds nice, because you can just plug in a library and let it do the dirty work. But we don’t have enough textual data for each photo to make full-text results relevant — all we have is the photo’s original folder name, which is also used to generate the captions.

For example, a pool photo might be put into a folder called “Pool”, or if the photographer was feeling nice, perhaps “Pool/Infinity Pool”. So we generate one or two tags from that data. And we also use the metadata associated with the photo’s hotel, such as the hotel name, type, and location.

Armed with tags, the next step was to reduce duplication and remove pointless tags with only a few photos, like “Villa Suite Grand Ocean View Room With Double King Bed”. We did this via a combination of a manually-prepared “tag merge spreadsheet” and some Pythonic scripting goodness.

The tags are all stored in singular form, but the search code recognises plural forms too. This is done via a lookup table created using a pluralize() function (see ActiveState recipe).

Our tagging isn’t perfect, of course. One thing it doesn’t yet handle is synonyms — our autocomplete provides clues for what the user can type, but at present we more or less force them to use our keywords. For example, you have to type “new york bathrooms” and not “new york restrooms”. Also on the radar is to allow users to add their own tags.

Autocomplete

The first piece of back-end technology you use when doing an Oyster Shots search is the autocomplete. We use Ajax (via jQuery) to fetch the autocomplete results as you type. Results need to come back fast, and our Python backend can handle about 3000 calls per second (though of course you won’t get that across a real HTTP connection).

An autocomplete lookup uses sorted indexes with Python’s built-in “bisect” module to do a binary search. Each binary search is of course O(log(N)), where N is the total number of items in the index. Python’s “bisect” module has a fast C version just to speed things up even further.

We have one index for whole-name matches and one for single-word matches. For example, if we looked at just the Las Vegas sections of the indexes we’d see something like this:

name_index = [

('lasvegas', LocationEntry('Las Vegas')),

...

]

word_index = [

('las', LocationEntry('Las Vegas')),

('vegas', LocationEntry('Las Vegas')),

...

]

If your query is “las vegas”, both indexes will match to give you Las Vegas, but if you just type in “veg” or “vegas”, the word_index will match and give you results. After the binary search we merge and sort the results: name matches are prioritized over word matches, and each match type has its own priority.

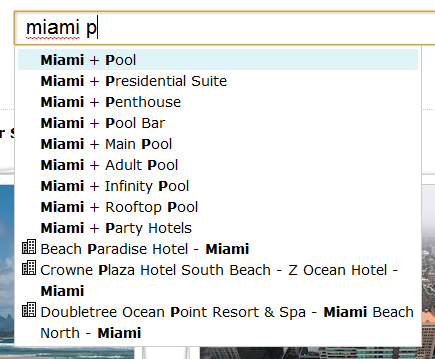

If there are no results, the autocompleter switches to multi-tag matching mode, which chops words off the end of the query until there are matches (if any), and then combines the first result of that with results from matching on the rest of the query to produce multi-tag matches. For example, if you type “miami p”, nothing will match directly, so we combine the first result for “miami” with results from “p”, giving “Miami + Pool”, “Miami + Presidential Suite”, etc.

Sorting and searching

The first step here was to read Donald Knuth’s The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 3, Sorting and Searching — I did this one morning on my subway commute to work, and then jotted down the answers to all the exercises on the commute home.

Seriously though, the authors of Python have read Knuth for us, and Python’s dict implementation is probably one of the fastest general-purpose hash table implementations on the planet. Our search code makes use of them liberally — dict lookups are fast, RAM is cheap, so why not cache 300,000 Image objects with a bunch of dicts? The two main caches map tags to images and hotels to images. Each value is a pre-sorted list of Image objects to speed up the sorting and pagination process.

The code also makes heavy use of Python’s built-in set objects to keep track of what we’ve seen, various filter options, etc. Sets use dicts under the covers, so lookups and insertions are both O(1) and fast.

Performance

Choosing good algorithms and data structures is much more important than which language you’re programming in. We chose Python because it allows us to iterate and write features quickly. Python compiles to simple and fairly unoptimized byte code, so it’s not known as a “fast” language, but because its data structures and built-ins are heavily optimized and written in C, it’s “fast enough”. (In fact, C++ hash_maps are significantly slower than Python dicts.)

As mentioned above, we’ve chosen our data structures carefully and made heavy use of dicts to cache things. But you have to be careful — partly because Python is flexible and dynamically typed, it’s easy to hide an O(N) or even an O(N2) operation where you meant an O(1) one. For example, consider the following (more or less real) code:

for image in images:

if image.hotel_id in hotel_ids:

...

If hotel_ids is a set, as it should be here, this is an O(len(images)) operation, but if it’s a list, we’re talking O(len(images) * len(hotel_ids)), which could be a very significant difference. You can shoot yourself in the performance foot in any language, but Python’s conciseness means it’s relatively easy to hide a really slow operation in a comparatively innocent-looking line of code.

Up next

So there you have it (or some of it). In our next blog entry, our lead front-end developer Alex will describe the fancy CSS and JavaScript he uses to make the front-end side of Oyster Shots so slick.