microPledge: our startup that (we wish) competed with Kickstarter

November 2022

Go to: Overview | Why we failed | IP for sale | What we learned | Conclusion | Timeline

I recently read Paul Graham’s tweet about how founders who fail are usually admired, as long as they made something good, and understand why they failed.

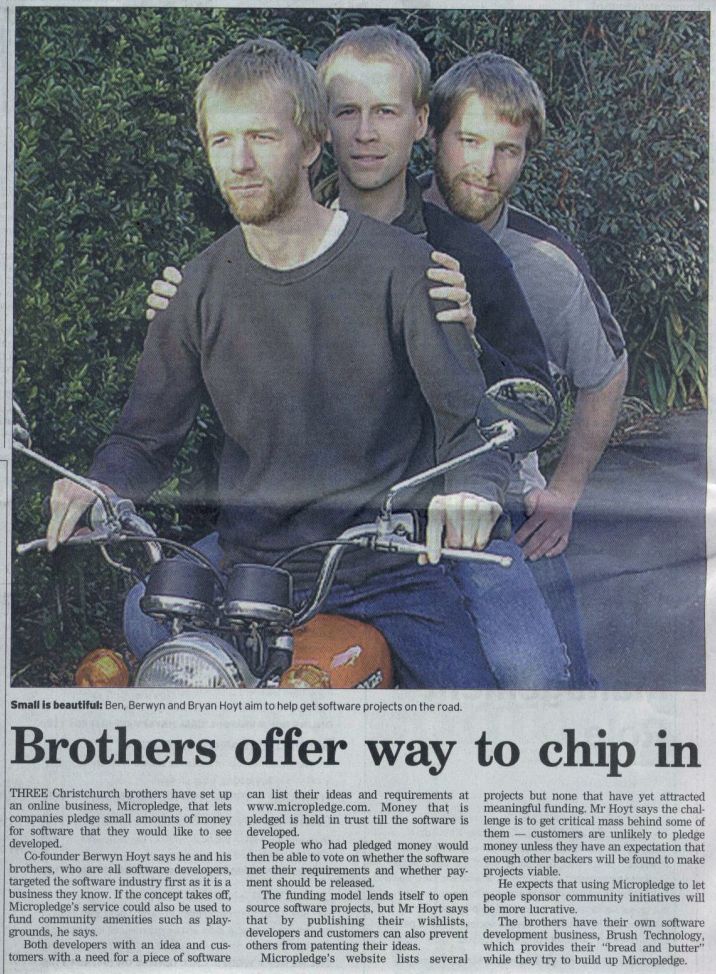

When two of my brothers and I launched our crowdfunding startup “microPledge” in 2007, we certainly tried to make something good: a crowdfunding platform any project could use, with a focus on software projects.

And I believe we know why we failed: our first version was overly complex rather than a minimum viable product, and we created it before testing it with and selling it to potential users. Then there was the PayPal legal issue which finished us off.

This article provides an overview of our startup, digs into our mistakes and what we learned, and gives a timeline of events for the record. It also looks at why Kickstarter took off, but microPledge did not. What microPledge did do, however, was kickstart our careers.

Overview and origin of microPledge

Back in January 2006, my brother Berwyn had the idea for microPledge on his commute to work. The seed idea was something like, “Imagine getting all your neighbours and friends and grandma to each chip in $20 to build a local playground. All we need is a web tool to enable these new creations!”

Shortly after this he contacted my brother Bryan and myself, to see if we wanted to help build this. Bryan had just started his own web design company, and joined right away. I was a couple of years out of university; I’d been reading Paul Graham’s essays on startups and was keen to join. I’d also been eyeing the Python programming language and wanted to start using it.

It was great timing – the term “crowdfunding” was first used in August 2006. We built the platform in about 12 months from June 2006 to July 2007, and launched in August 2007, just as crowdfunding was becoming a popular concept.

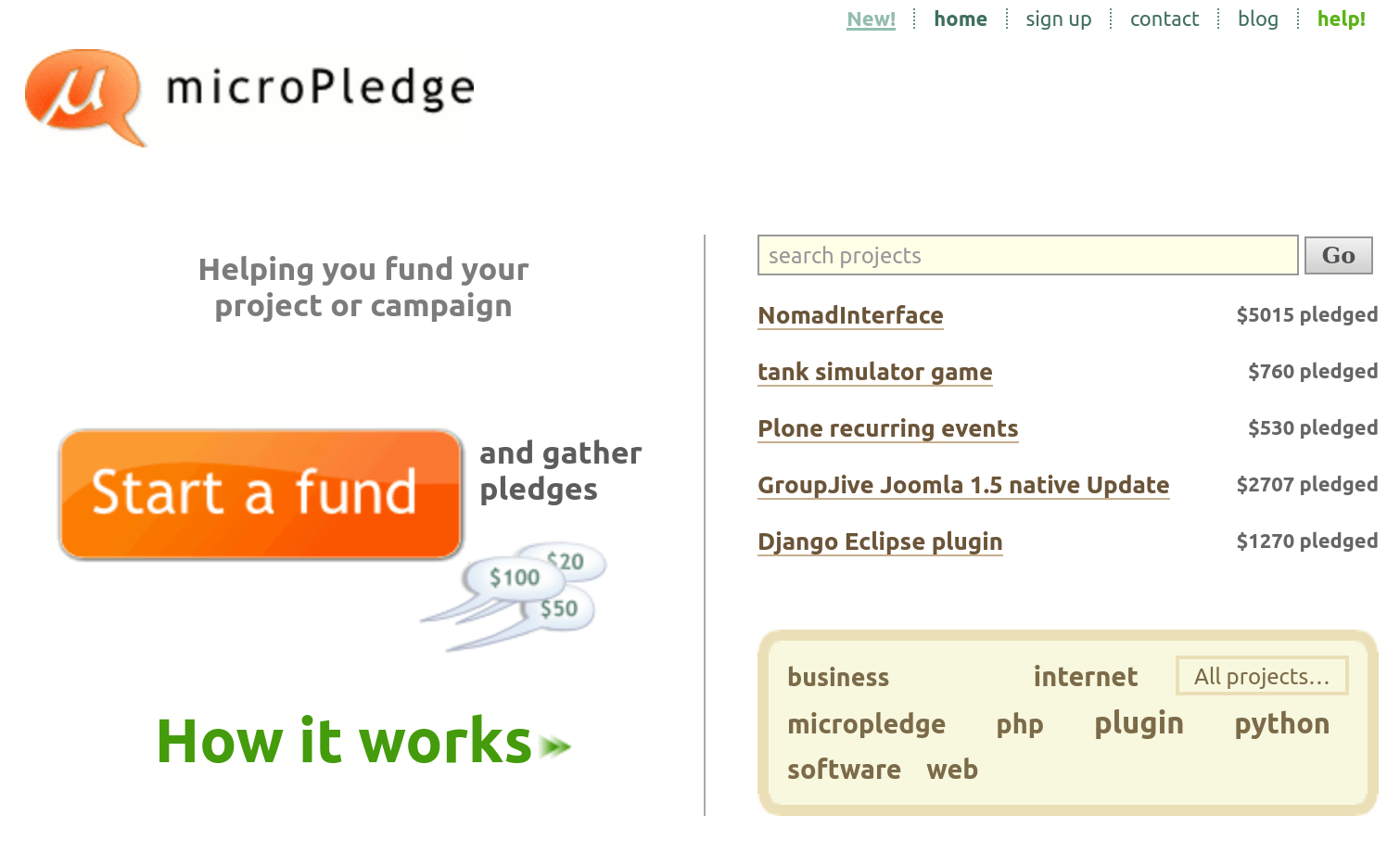

Here is a screenshot of the original microPledge homepage (which is preserved on our read-only website).

We initially focused on helping people fund software projects, but we also wanted the system to work for any kind of physical project.

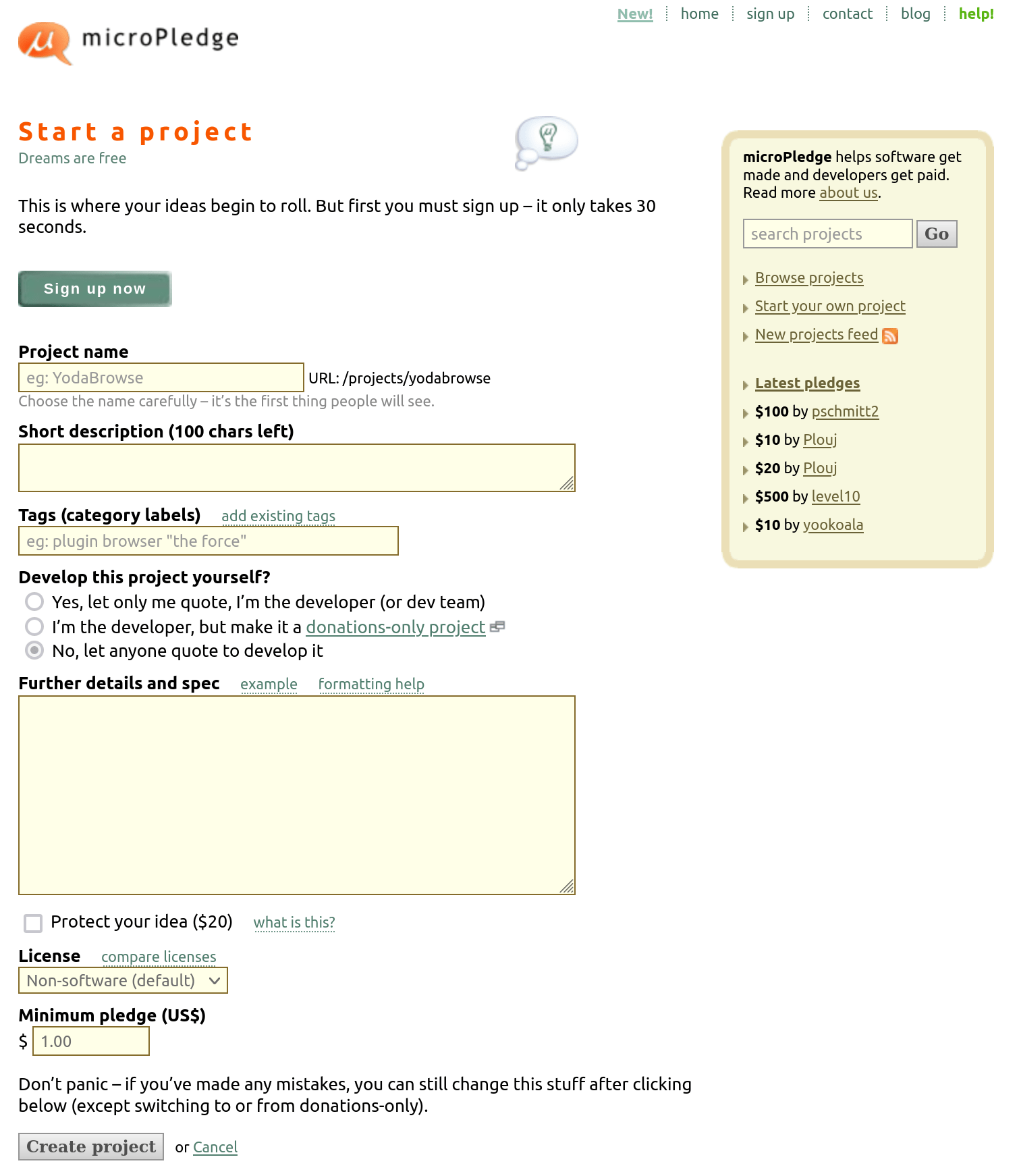

Creators who wanted funding could easily create a project: we carefully kept the start-a-project form to one simple screen:

From there, project creators could set a target amount, then wait for pledges to come in. Pledged money was transferred to a trust account until payout time.

We used PayPal as our payment system. Back then it was one of the few providers that let you pay money out to others. However, we didn’t read their fine print carefully enough when starting: the short version is that PayPal does not like you holding money in trust. But more on that below.

We got a small amount of money from angel investors: about NZ$10,000 from family and NZ$60,000 from a friend. At the time we estimated that investment as worth a third of the company, so we founders kept a two-thirds share between us. This money was enough to pay minimal living costs for the three of us while we developed it full time.

Looking back, that period was a lot of fun: working with my brothers on our very own startup, learning Python, SQL, and web development.

Why we failed

microPledge wasn’t a complete failure: we had about 1200 users, 100 projects created, and $25,000 total pledged. A small handful of those projects reached their target. So we got a little bit of traction, then floundered and ran out of money, and ultimately failed.

Below I describe the various reasons why I think we failed. It’s easy to see these things in retrospect, but they weren’t obvious to three young software geeks in 2006.

Most of these things are probably noted in any Startups 101 article – in the list of “what not to do”. Hindsight is a wonderful thing.

Over-complicated progress and payout system

One reason microPledge didn’t take off was that the system was just too complicated. Remember that we were three engineers with little marketing know-how. Instead of making a dead-simple “version 1”, we created a Rube Goldberg machine: technically brilliant, but hard to understand.

We designed an incremental payout system, letting the project creator drag a slider to say (for example) “I’m 30% done”, and upload evidence – photos or source code – to show the progress they’d made on the product so far. Pledgers would be notified, then they would drag the slider to vote, and after a voting period the creator would get 30% × TotalPledged × AverageVotePercentage.

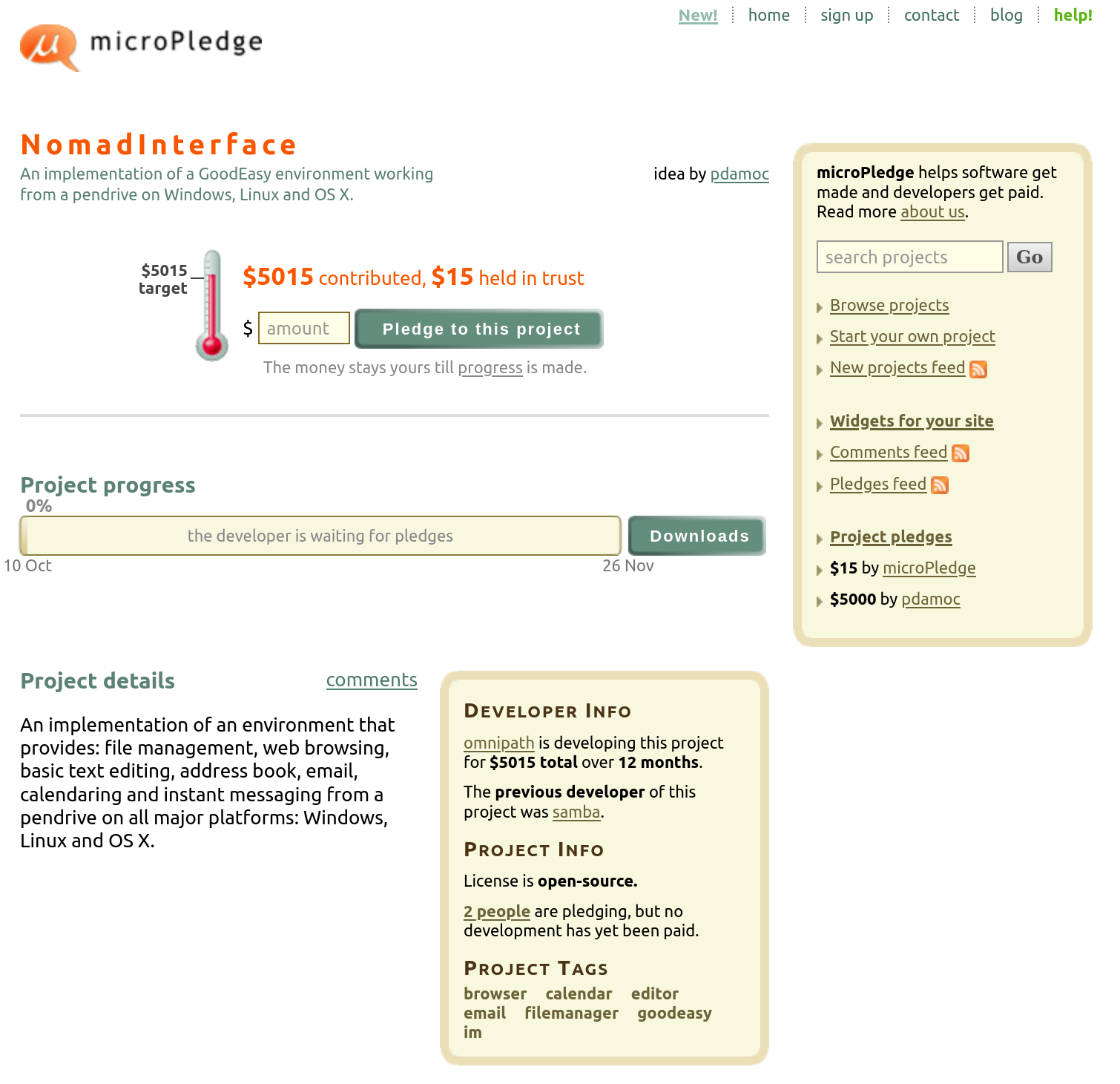

Here’s a screenshot showing one of our project pages (this project reached its target but was never developed):

There were a lot of details, as the length of our multi-page project creator FAQ showed. In addition, we had a full-fledged project quoting system, so that anyone could add a project suggestion, then developers could quote for it, and the best quote would win.

Don’t get me wrong: microPledge had an adequate UI for a complicated system. We spent a lot of time figuring out the details! The “fundraising thermometer” and the progress slider were clear and visual, details were presented slowly behind tooltips, and both creator and pledger were guided through the voting process.

Our mistake was earlier: we designed an intricate system … that nobody needed. Kickstarter, which launched two years after microPledge, succeeded with a simple “Back this project” button, and project creators either get all the money (if the goal is reached), or none. There’s no progress stages, no voting, no payout calculations.

We didn’t design this complex system for complexity’s sake; we wanted to solve the problem of pledgers trusting creators to actually follow through and make the product. But it turns out people are pretty trusting, and most of the time, this works! There are relatively rare cases of Kickstarter creators that don’t deliver, and pledgers get grumpy. But they went in knowing the risk, and how grumpy can you get when you’ve only pledged $20?

In short, microPledge was too intricate for a minimum viable product, and too complicated compared to what users really wanted: pledgers just want a simple pledge button, and creators just want a payout.

Over-engineered software

When you put three software engineers with perfectionist tendencies in a room, they’re bound to over-engineer things.

For example, we developed our own mini-ORM instead of using something off the shelf (or just plain SQL). As a startup we should have focused on getting the job done, not writing framework-level code.

We spent a bunch of time tweaking PostgreSQL configs to use WAL logging (at the time, this was tricky to set up) so that we could proudly tell users we had up-to-the-minute backups. We could have written a 5-line script that used pg_dump to save a backup once a day.

I remember personally spending several hours implementing code to detect and handle hash collisions of random SHA-1 hashes. This basically can’t happen in billions of years, so I guess I needed to read an article on cryptographic hashes.

And we did all this without paying users or a meaningful revenue strategy! It had not yet sunk in that startups live or die based on generating revenue, not technical prowess in the code.

Something that would have helped with both of these “over-complication” points is having an artistic or business person on the team rather than another engineering-minded brother.

Emphasizing mechanics, not the finished product

If you look at our project page shown above, the most prominent part is the pledging and progress, rather than the product the pledgers will get. There’s only a small paragraph selling the project itself.

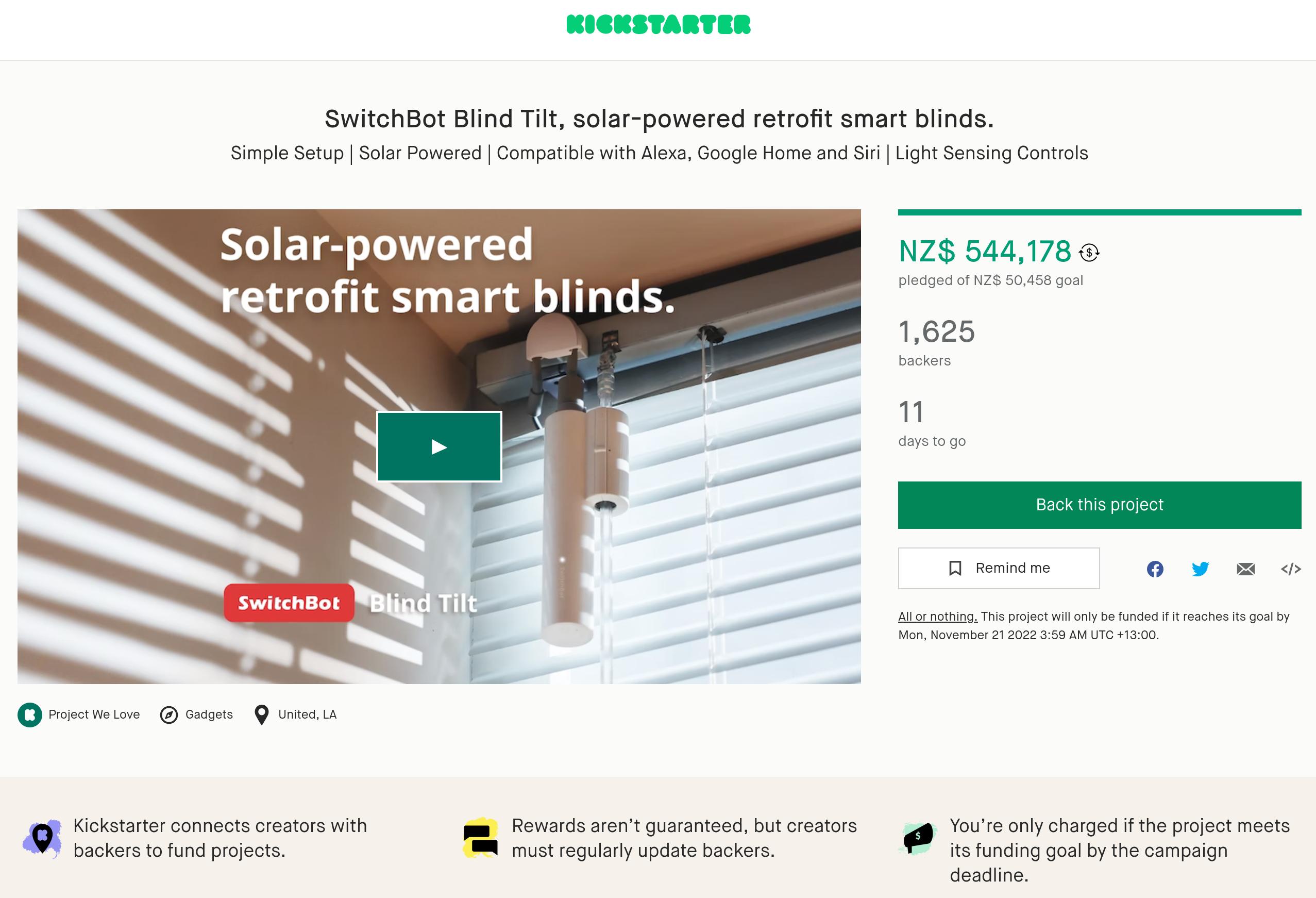

Compare that to Kickstarter’s project page, which leads with a big video selling the product being created, normally followed by a lengthy blurb about said product, intermingled with high-quality photos. Here’s the top part of a Kickstarter project page:

Kickstarter helps the creator make their (potential) product really shine. Our project page did not. And they guide you through making a great project page. Essentially, they’re training founders of these mini-startups to sell to their own audience.

I think we made this mistake because we were thinking of things from the creator’s perspective rather than the paying customer: the pledgers (or in sales terms, the buyer). Along the same lines, “Kickstarter” is a somewhat better name than “microPledge”: it emphasizes the product output rather than the pledge input.

Poor choice of focus

While microPledge did support physical projects, most of our promotion efforts were for software projects, particularly as a means of funding open source software.

We started there because that was what we knew, and software distribution is easy. However, in retrospect that was almost certainly a mistake: there is money in open source, but it generally comes from enterprise support and extensions, not crowdfunding.

Kickstarter and other pledging websites tend to focus on real, physical projects. It’s much easier to get regular folks to chip in for a hardware gizmo or a new type of shoe than for software.

Not grasping what users really needed

Another big reason for failure was that we built the system without sounding out the market, and without testing what real users actually wanted.

We did do some promotion, of course, mostly to software project creators that we thought might find it useful. For example, we interacted a bunch with Graham Dumpleton, maintainer of the mod_wsgi extension for Apache (which we used to serve microPledge). We convinced him to use microPledge for a donations-only project, and he gave us some valuable feedback along the way.

And in September 2007 we got a little bit of press in the Dominion Post, a New Zealand newspaper (the article was also posted to Stuff.co.nz, their sister news website).

That said, we should have been selling it to potential project creators and real-life pledgers from early on … before spending 12 months developing it. We should have iterated on the product often based on this feedback. Probably the main reason we didn’t was that for us, writing code was fun; picking up the phone was not.

PayPal legal issue

Within a few months of launch, we could already see it wasn’t going great. However, what put the nail in the coffin was our legal saga with PayPal a year after we launched.

How microPledge handled money was this: we accepted pledges via PayPal, then transferred that money into our trust account, and finally paid it out to project creators as a project made progress.

It was the “holding money in trust” bit that was our downfall. This was really our fault: we hadn’t read PayPal’s terms of service closely enough, and holding money in trust was one of the things they prohibited.

PayPal found out because a credit card scammer started trying to launder money through our site. This got discovered by PayPal, who then audited us and noticed we were holding money in trust.

We had good intentions, and of course we paid out as promised, but we found out there’s very little “pal” in PayPal. Once they found out we were holding money in trust, they immediately froze our account, and despite many calls to their support line to plead our case, they kept our money locked up for a 6-month period.

We were frustrated, and users were understandably upset. We considered various options and other payment providers, but microPledge hadn’t gotten the traction we’d hoped for in any case, so this 6-month freeze was basically the death knell.

Attempt to sell company IP

After throwing in the towel, we changed tack and attempted to sell the microPledge pledging system to interested parties. However, it turns out intellectual property isn’t worth much – we got a few bites, but not a buyer.

And this was at prices that were basically giving it away – we were just trying to recoup some costs. Quoting from our “Prospectus”, potential buyers could purchase one of the following:

- A license for the complete web software priced at US$7,500, with complete rights to the source code and alteration rights.

- All the above plus complete ownership of the platform including exclusivity, rights to on-sell, etc. Price to be negotiated – offers over US$35,000.

We also attempted to sell the company on Flippa.com. Once again, this didn’t go much of anywhere. In the end, all our attempts at selling fizzled out, and we ended up letting the micropledge.com domain expire a couple of years later.

What we learned

Failure is a good teacher, and we learned a lot during these couple of years.

Business

On the startup side, what we learned was essentially the reverse of the “why we failed” list above:

- Start with a dead-simple version 1 (the KISS principle).

- Emphasize the output that the (paying) customer wants.

- Focus on paying markets; maybe not open source.

- Sell first – before you write any code.

- Read your payment system’s fine print. :-)

We did get valuable business experience from all this: my brother Bryan created microPledge’s parent company, Brush Technology, which Berwyn and I helped run for several years after microPledge failed, and which still operates today as a software and electronics consulting company.

A few years after microPledge, we started another startup, Hivemind, that made a tangible product: an electronic monitoring and reporting system for beehives. Selling to beekeepers is hard, but this startup went significantly better, and we put into practice several of the lessons we’d learned earlier.

Technical

As a programmer without formal training in software engineering, I don’t think it was till years later that I realized just how much I’d learnt from our startup experience.

On the technical side, I learned web development (HTTP, HTML forms, and enough CSS and JavaScript to be dangerous). I learned Python development, as well as relational databases and SQL (specifically PostgreSQL). Bryan probably knew the most about these when we started, though I think all of us learned a lot.

I also learned about web frameworks: we evaluated Django, but ended up using web.py, a micro-framework created by Aaron Swartz. I’m surprised it’s still actively maintained. I still like my web tools small and light: more library and less framework.

Another thing I learned was what I call “diff testing”. This was Berwyn’s idea, though I’m sure it’s not original with him – I’ve heard it referred to as “snapshot testing” or testing with “golden files”. The basic idea is to save your test’s expected output to a file and commit that snapshot to source control. Then when you run the code under test, you write output to a new file, and the test is simply to diff it against the snapshot. I’ve used this technique for many projects since then; it’s particularly good for data transformation tasks.

But perhaps the most important thing I learned was teamwork: how to create software in teams, how to split up and organize work, the importance of using good tools, and so on. microPledge was my first job where I was developing with a team and using revision control. Most of this mentorship came from our older brother Berwyn, who’d worked at a medium-sized software company for several years.

Conclusion

My main take-away is that all of that learning-from-failure was very valuable to our future careers. Particularly valuable for my own career was the technical experience developing web apps with Python, and learning how to build software in a (small) team.

Would we have succeeded if we had created microPledge knowing what we know now? I think we’d have a very good chance. We’d create a much simpler system and promote it to the right people.

However, one thing we still wouldn’t have: a presence in Silicon Valley. There is a reason Paul Graham and company moved Y Combinator from Boston to Silicon Valley. It’s a lot harder to raise funds for startups like this in little old New Zealand. That said, I think we could have been a local, smaller-scale success.

Kickstarter succeeded – and kudos to them – by being simple and clear, and by making the system focus on the product the creator is trying to sell rather than the money mechanics.

Would I do a startup again? Till now I’ve thought, “Nope. I want to work for more stable companies for a while.” But writing this surprised and re-inspired me. Maybe it’s time again!

I’d love it if you sponsored me on GitHub – it will motivate me to work on my open source projects and write more good content. Thanks!

Timeline

Below is a timeline for microPledge (mostly for my record!).

- Jan 2006: Berwyn had the original idea on his commute

- Jan 2006: Initial Subversion commit

- Feb 2006: First meeting with the three brothers about μPledge (our original name). Quote from the minutes: “We imagine (vainly?) that we can have something releasable in 6 months.”

- Mar 2006: Decided on web framework: we chose web.py over Django because it was “1/6th the learning curve” and felt much lighter

- Jun 2006: First code commit: code structure and start of mini-ORM

- Jul-Dec 2006: Initial code: data model, HTML generation, server setup

- Jan 2007: PayPal handling code

- Feb-Mar 2007: Page templates, project page, progress slider, and so on

- Mar 2007: Wrote microPledge patent application

- Apr-May 2007: Pledging and voting, ability to withdraw funds, sign-in, allow developer to pull out with 10% penalty

- May 2007: File uploads and project thumbnails using Amazon S3

- Jun-Jul 2007: Flurry of testing and bug-fixing, PostgreSQL WAL backups, finished server setup

- Aug 2007: Launch! Press release, submission to Slashdot.org, and outreach to several open-source projects

- Sep 2007: News article in the Dominion Post

- Sep 2008: PayPal suspended our account due to us holding money in a trust account

- Oct 2008: Asked our 1200 users to pledge $10 each to “keep microPledge going” (switch to a different payments provider)

- Dec 2009: Attempted to sell microPledge software or IP

- Feb 2010: Attempted to sell the company on Flippa.com

- Feb 2013: We let the

micropledge.comdomain expire: the end of an era.