The Penguin History of New Zealand

June 2021

My parents are American, and although I was born in Tennessee, when I was a baby they moved the family to New Zealand. I grew up and went to school in small-town New Zealand and consider myself a Kiwi at heart. However, the school I attended didn’t teach much New Zealand history (not that I would have paid much attention if it had), and with my parents being from the States I didn’t really learn any at home either.

I had imbibed the very basic outline of our country’s history: first came the Māori, then came the Europeans (Pakeha), there were a few skirmishes, some early mission work, somewhere in there the Treaty of Waitangi, at some point we formed a government separate from England, and, well, that was about the extent of my knowledge. Additionally, most of what I knew about Māori culture was from Māori kids in the neighbourhood and at the town pools, and from the news – which, to me growing up, seemed like it was mostly about land claims from the distant past.

Not really being a history person, I never had much inclination to fill in the gaps. Then, this past Christmas, my niece gave me The Penguin History of New Zealand, and I’m really grateful. I highly recommend it, particularly if you are like me and don’t remember much New Zealand history from growing up.

I had a brush with The Penguin History many years ago when I wrote an article about the Wellington waterfront strikes of 1913. I remember being fascinated at the time that “something actually happened” in our history. But for whatever reason – perhaps because I had to return the book to the library – I only read the chapter on the waterfront strikes, and not the rest of the book. But the rest of the book is even better.

The main thing I appreciated was how well-researched and balanced the book was. The author Michael King (who died in 2004, just a year after the book was published) was a prolific New Zealand historian, has obviously done his homework, and had a particular interest in Māori culture and Māori-Pakeha relations. The “further reading and acknowledgements” section at the end of the book shows just how much research he did, and he himself has published over 40 books on different aspects of New Zealand life and history.

The Penguin History gave me an appreciation not just of Pakeha history, but of Māori history and culture in a way which the modern news media does not. Today we see headlines and stories which often amount to “Māori good, colonists bad” (or sometimes the opposite, from one’s racially insensitive uncle). The truth, as King shows in detail, is rather different: significantly more nuanced, and far more interesting. In addition, simply making people feel guilty about their own people and history isn’t a great way to help them understand and appreciate other cultures. Providing the history, telling stories, and showing how we got where we are – those do help.

The book starts with the arrival of the first Polynesians to New Zealand in the 13th century, explaining not just how courageous they must have been to come in small boats, but also how advanced their seamanship was. We don’t have written records of their travails, of course, but scientists and historians can tell roughly when the first settlers arrived, what animals they brought with them, and that they likely made many voyages to (and back from!) New Zealand.

Neither does King shy away from discussing facts that portray Māori in a less favourable light: the fact that they killed all the large, flightless Moa in a couple of generations after arriving (they needed to eat, and it was easy food), as well as discussing their inter-tribal warfare and cannibalism. Similarly, King describes the varied and complex British motives and approaches, and again doesn’t hesitate to discuss what they did well, as well as what they did poorly – the unfair land grabs, the patronizing and racially-insensitive attitudes over the years, and the hasty obliteration of tens of thousands of seals and other animals.

One of the things that fascinated me was the history of the Moriori people. I think many of us learned that “the Moriori people got here first, and then the Māori arrived and wiped them out”. It turns out this is a myth that grew out of a half-truth. The Moriori are simply early Māori that settled on the Chatham Islands in the 16th century. They developed a highly peaceable culture there, in contrast to the more warrior-like “mainland” Māori. However, in 1835, some disenchanted Māori from the Taranaki region commandeered a British ship, sailed to the Chatham Islands, killed about 300 Moriori and enslaved the others – an enslavement that lasted almost 30 years.

That is partly where the myth that “Moriori were here first and Māori wiped them out” came from. In reality it only happened on the Chatham Islands and even there it didn’t wipe them out – though it vastly reduced their numbers and set them back a lot. The Social Darwinism of the early 20th century saw this story as almost positive or at least inevitable: a weaker race taken over by a stronger, more advanced one (and no doubt soothing the consciences of the European colonists who had pushed Māori aside). The “Moriori were here first” story was turned into a myth-like tale and published in several New Zealand School Journals, and that was what a couple of generations of New Zealanders learned as fact. It was widely disproved over the years by historians, but the myth stuck around for a long time – I heard it many times growing up in the 80’s and 90’s, and I’ve heard it more recently as well.

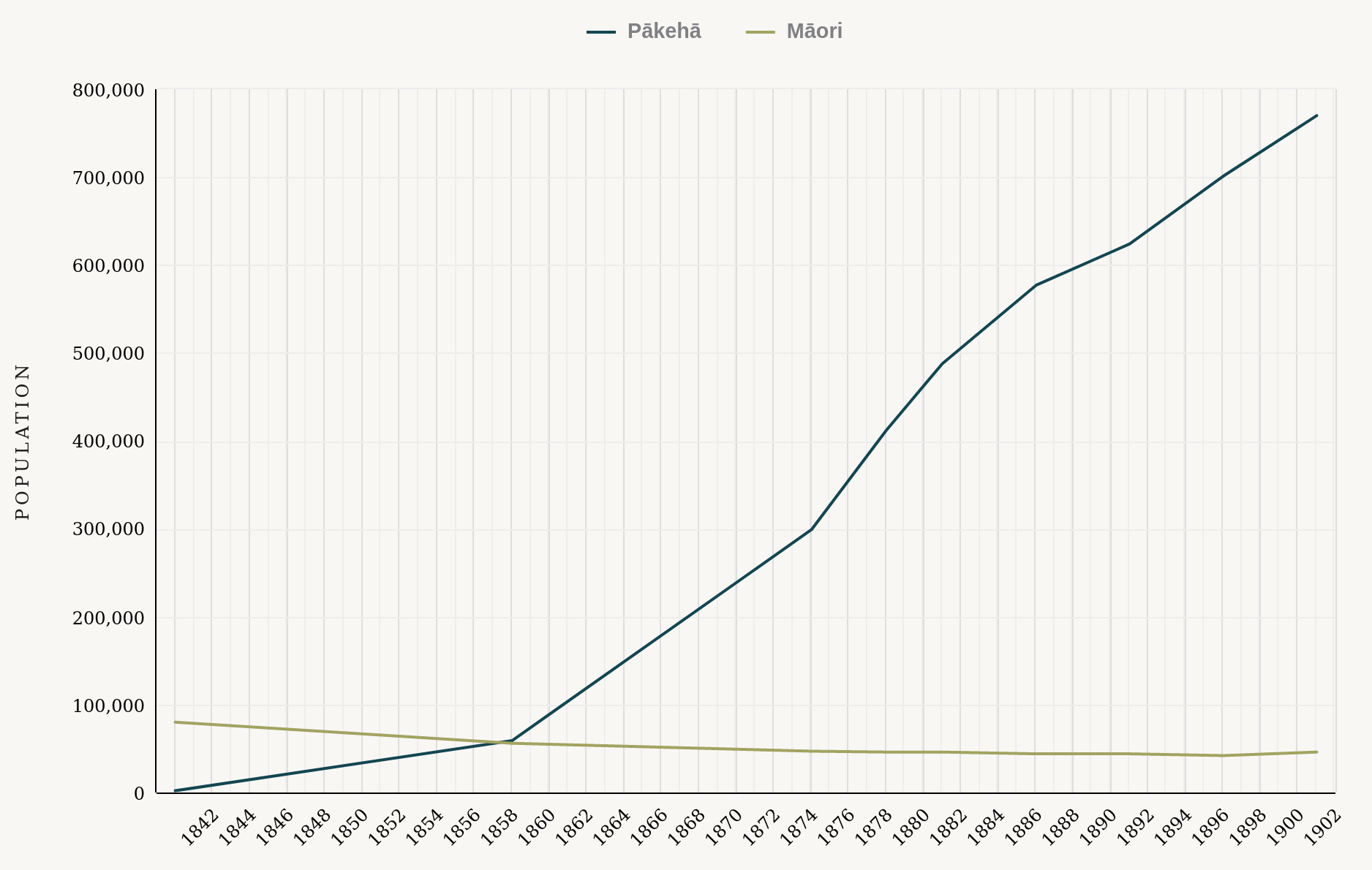

Another thing that struck me was just how quickly British immigrants came. In 1830 there were about 300 European settlers in New Zealand. Just fifty years later, in 1880, there were around 400,000. Their number surpassed the Māori population (around 70,000) by about 1860. So when the Treaty of Waitangi was written in 1840, Māori sentiment was along the lines of “sure, you seem like decent folks, we’ll sign” (my paraphrase), but little did they realize the massive number of Europeans that would settle in the country over the next few years and how much they would change the landscape, both figuratively and literally. In my mind, those numbers in that short a timeframe go a long way to explaining the roots of Māori-Pakeha tension.

The graph below, from Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, shows this rapid population growth visually:

It was interesting to me that Māori, up until relatively recently, didn’t consider themselves one people, but saw themselves as individual tribal groups, or iwi. Culture developed tribally, family connections formed this way, feuds happened between tribes, and so on. Ironically, lumping all the tribes into one “Māori” people group was (at least at first) a lens the Europeans saw with. Today, for various reasons King goes into, Māori often do identify themselves as belonging to one people, but tribal identity is still very important (most South Island Māori belong to the Ngāi Tahu tribe, for example).

In any case, King’s book goes into a lot of depth about the whole subject of Māori-Pakeha tension over the years, the haste in which the Treaty was translated, the land rivalries (greed, misunderstandings, battles), the huge Māori move from country to city in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s that amped things up again, the legal change in the 1990s that allowed Treaty land cases to be debated right back to 1840, and so on. He also shows how good a foundation we do actually have for living together in this country (especially compared to countries like the U.S. with a history of race-based slavery and institutionalised segregation). A lot of this was new to me, and I found it very insightful and helpful.

I realize I’ve written many paragraphs here about the parts of the book that address Māori culture and Māori-Pakeha interaction, because that’s the area I knew least about, but King’s book covers much other ground, too. For example, Captain Cook, his incredible legacy, and the respect contemporary Europeans and Māori had for him. King also touches on the early missionary work by Samuel Marsden and Henry Williams. He talks about the early development of rugged Kiwi male culture in the mid-1800’s, when there were twice as many male settlers as female – and how various government programmes tried to address the imbalance. He talks at length about New Zealand’s involvement in both World Wars. He discusses feminism, the sexual revolution, Asian immigration, the Great Depression, our political system, the introduction of the welfare state, the formation of the National and Labour parties … the list goes on.

King’s book is an amazing tour of our country’s history, Māori and Pakeha. It sounds like our higher-ups are talking about reworking the public schools’ history curriculum as I write this: if The Penguin History of New Zealand is used as a base, I don’t think we’d be doing too badly. Do read it! If you live in Christchurch, you’re welcome to get in touch and borrow my copy.