Fast pentomino puzzle solver ported from Forth to Python

July 2017

Summary: Based on a Forth pentomino puzzle solver that my dad wrote and refined over the years, I wrote a version in Python. It uses a brute force (but clever) approach using code generation to find all 2339 tilings of the 12 free pentominoes on a 6x10 board.

Programming and pentominoes

My now-retired father was a full-time pastor and a hacker on the side. His enthusiasm for nerdy things like writing Forth compilers and low-level graphics libraries got me into programming when I was about 14. In fact, the first major program I wrote was Third, a self-hosting Forth compiler with the primitives written in 8086 assembly.

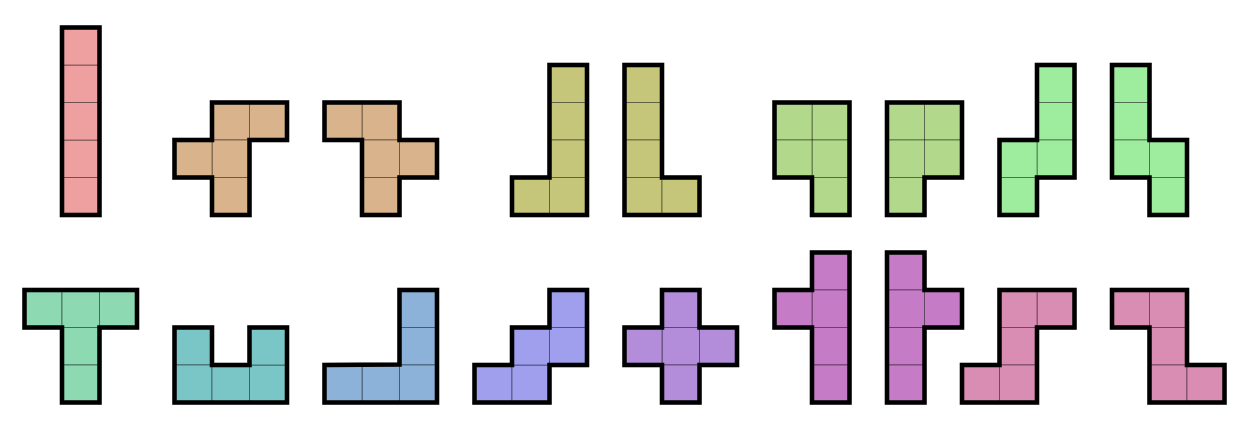

Over the years, Dad also wrote various incarnations of a program to find all solutions to the pentomino puzzle. Pentominoes are kind of like Tetris pieces, but with five squares instead of four. There are 12 “free” pentominoes, meaning free to rotate or be mirrored, 18 “one-sided” shapes if you include mirroring, and 63 shapes if you include mirroring and rotations.

Here’s a picture of the 18 shapes, with each of the 12 free pentominoes shown in a different color:

Each of these 12 pieces has a more-or-less standardized letter to name it, kind of corresponding to the piece’s shape. In the diagram above, the first row shows the I, F, L, P, and N pieces. The second row shows the T, U, V, W, X, Y, and Z pieces.

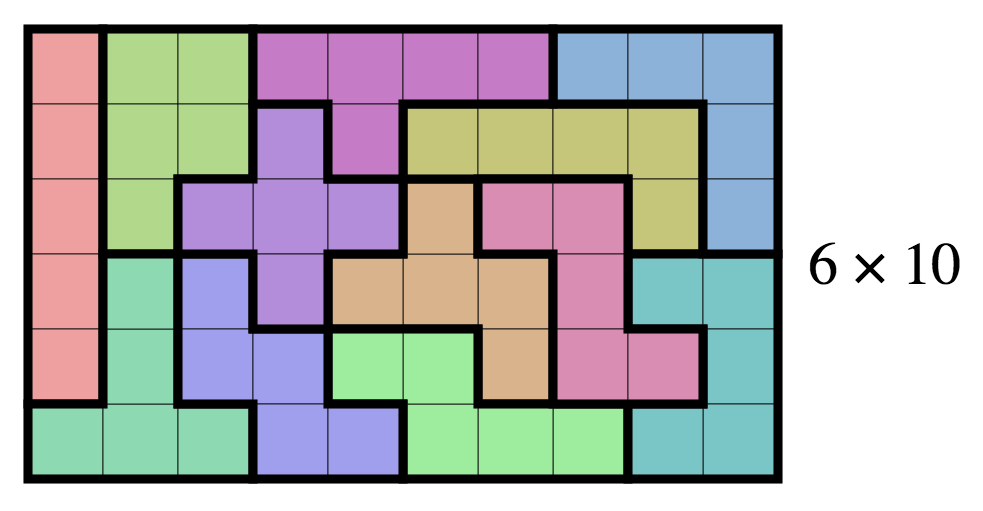

If you’re patient, you can fit these 12 five-square pentominoes exactly on a 6x10 board – or a 5x12 or 4x15 or 3x20 board. There are exactly 2339 solutions to the 6x10 puzzle (excluding rotations and reflections), but it’s usually hard for a person to find even one – it usually takes a newbie an hour or two.

Spoiler alert – here’s an example solution on a 6x10 board:

Dad’s solver

Dad started programming back in the punch card days, when you punched out your code on a stack of cards, and then submitted them and waited for your batch to run and produce results overnight on the university mainframe.

His first solution to the puzzle was slow, and didn’t finish in his 20-minute overnight timeslot. The algorithm was pretty much what you’d expect for a first pass: start with the first of the 12 pieces, place it, and then recursively try to solve the puzzle with the remaining pieces. The problem is, you search a ton more than you need to.

For example, if you place the X piece near the beginning, all the rest of your placing and backtracking is useless, because that one-square hole at the top-left is never going to be filled:

┌──────┐

│ x │

│xxx │

│ x │

│ │

│ │

Over time, Dad came up with a different approach: create a 63-leaf binary tree (one leaf for each shape) that you traverse starting at the next empty square, place a piece based on the traversal branch, and recursively solve the remaining puzzle. If you create your tree correctly, and always move right and down, you’ll never create wasted holes.

There’s still backtracking and you still try a lot of pieces (2,455,939 for the 6x10 puzzle), but a lot less, and you can solve it in a reasonable amount of time – a couple of seconds on modern hardware, though it was a couple of hours in the 70’s when Dad first solved it.

Dad was into Forth, so pretty soon he wrote a version in Forth. One clever optimization was, instead of generating the tree directly, use the tree to generate code which in turn solves the puzzle. The generated code is just a whole bunch of nested if statements. In Forth, you can do this kind of meta-compiling using POSTPONE. If you’re interested in learning a bit of Forth, his Forth pentomino code is here (it runs under Gforth).

To give you a little taste of some of the Forth code-generation functions:

\ Generate code to put piece on board

: place-piece ( p# -- )

pos-stack 5 over + swap do

dup postpone literal

postpone over i c@ postpone literal postpone +

postpone c!

loop drop ;

\ Generate code to remove piece from board

: lift-piece

pos-stack 5 over + swap do

0 postpone literal

postpone over i c@ postpone literal postpone +

postpone c!

loop ;

\ Macro to generate code to recursively test availability of

\ a piece and mark board and piece availability accordingly

: leaf-test ( pc# -- )

Pa + >r ( R: pc-addr )

\ Is piece available?

r@ postpone literal postpone c@ postpone if

\ Mark unavailable

0 postpone literal r@ postpone literal postpone c!

\ Increment number of tries

1 postpone literal postpone Tries postpone +!

\ Place piece, recurse for next piece, then lift piece

r@ Pa - 1+ place-piece

postpone dup postpone next-piece

lift-piece

\ Mark available again

-1 postpone literal r> postpone literal postpone c!

postpone then ;

My Python version

My solution follows Dad’s, but instead of compiling Forth using POSTPONE, it generates Python source code for a recursive solve() function, and then evaluates the entire string using exec(). This means that for each empty square, we’re using the Python bytecode interpreter to walk the 63-leaf binary tree to find a piece that fits.

The ORIENTATIONS string in my Python version is a mini DSL – stolen from my dad’s program – that describes all 63 piece orientations. The letters A-Z and a in the string represent positions in the 8x5 rectangle below:

...ABCDE

FGHIJKL.

.OPQRS..

..XYZ...

...a....

And the lower case letters filnptuvwxyz are letter names of the 12 pentomino

pieces. A . means unrecurse. Here’s the ORIENTATIONS string in its entirety:

ABCDEiIlJyKyLl.IHnJpKuQv.JKpRt.KLnSv..IHGnJpPwQf.JKpQpRp.QPzRuYl..

JKLnRfSw.RQuSzZl...IHGFlJyOzPfQt.JKyPfRf.POwQpXn.QRfYy..JKCuLlQtRf

Sz.QPfRpYy.RSwZn..QPOvRtXnYy.RSvYyZn.YXlZlai....

Below is a snippet of the 1000 lines of code generated by generate_solve():

def solve(board, pos, used):

global _num_tries

if len(used) == NUM_PIECES:

# We've used/placed all the pieces, show solution!

display_solution(board)

return

# Find next empty square on board

while board[pos]:

pos += 1

if not board[pos + 0]:

if not board[pos + 1]:

if not board[pos + 2]:

if not board[pos + 3]:

if not board[pos + 4]:

if 'i' not in used:

_num_tries += 1

used.add('i')

board[pos + 0] = 'i'

board[pos + 1] = 'i'

board[pos + 2] = 'i'

board[pos + 3] = 'i'

board[pos + 4] = 'i'

solve(board, pos, used)

board[pos + 0] = None

board[pos + 1] = None

board[pos + 2] = None

board[pos + 3] = None

board[pos + 4] = None

used.remove('i')

if not board[pos + 8]:

if 'l' not in used:

_num_tries += 1

...

You can run my Python solver with the -s argument to print the solve() source code instead of actually finding all the solutions. And -q puts it in quiet mode, finding all the solutions but not printing them.

See the Python source code or the full generated code.

A quick benchmark

It turns out GForth’s virtual machine is pretty fast! On Python 3.5, my Python solver takes 5 seconds to find all 2339 solutions (in quiet mode) on my 2.5 GHz macOS i7. Whereas the Forth version, using Gforth, only takes one second – almost 5x as fast. I think this is mostly due to Python’s dynamic nature: everything’s overrideable, and almost everything is a hash table lookup (for example, an innocent board[pos] access will look up __getitem__ in board.__dict__ and call the result).

Interestingly, on Python 2.7 my solver takes 11.6 seconds – less than half the speed when running under Python 3.5. The generated code is mostly a test of the CPython bytecode interpeter, so it seems like the Python core developers have done some great optimization work on the bytecode interpreter between 2.7 and 3.5 (and it looks like they’ve done a bunch more in 3.6). I’m unsure what the main gains are there, but I’d love to know – contact me if have ideas!

Perhaps even more oddly, PyPy, even with its JIT compiler, is slower than plain old CPython 3.5, at 10.7 seconds. Again, I’m not sure why that is, but I’m guessing it’s because the pre-unrolled, recursive solve() function doesn’t appear to be a “hot loop”.

Here are all the benchmark results in a table:

| Compiler | Time (s) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Gforth 0.7.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| CPython 3.6.1 | 4.6 | 4.2 |

| CPython 3.5.2 | 5.1 | 4.6 |

| PyPy 5.8.0 (2.7.13) | 10.7 | 9.7 |

| CPython 2.7.13 | 11.7 | 10.6 |

May the Forth be with you

All in all, it was a fun exercise learning about pentominoes, solving the puzzle, and reimplementing my dad’s Forth solution Python. I was going to say “the two languages are very different”, but then again, Forth is different from pretty much everything else. Even if you’re never going to use it professionally, it’s worth learning about! It’s rather dated, but I recommend reading Thinking Forth to get into the zen.

Please write your comments on Hacker News or programming reddit.