SEO for Software Engineers

February 2020

A few months ago I gave a tech talk on “SEO for Engineers” for our software developers. We (the SEO team) had found that many engineers didn’t know too much about Search Engine Optimization, and sometimes designed our consumer-facing pages in a way that wasn’t ideal for SEO.

So we thought it’d be useful to go over the basics of good SEO technique for the larger team … and now we’re sharing that information with you. There is a lot published about SEO, but most of it is written by SEO agencies — this article is written by engineers, for engineers.

Then vs. now

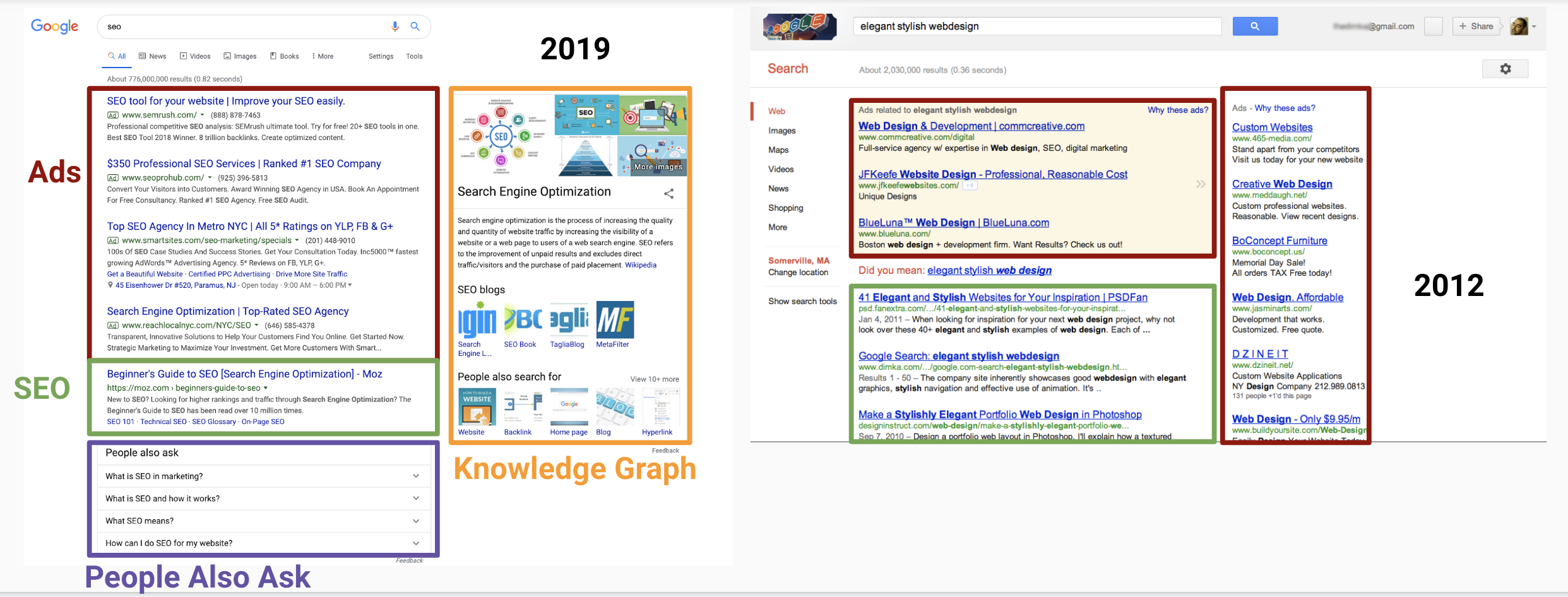

It’s worth looking at Google search results pages now compared to several years ago:

Even with the smaller screens in 2012, we can see 3 non-ad results without scrolling. In 2019 we see four ads, a bunch of Google Knowledge Graph items and “people also ask” answers, and then a single real search result!

It’s getting harder and harder to even appear on the results page without scrolling, arguably making good SEO even more important.

What is SEO?

SEO stands for “search engine optimization”. It’s a fancy term for doing things that make your pages rank higher in searches, with the goal of getting more and better traffic from search engines.

Because Google is the main search provider, this really means ranking higher in Google searches — but most of the things you should do for Google are good for all search engines.

Note that SEO is not SEM, “search engine marketing”, which is about paying for keyword-based ads. You can think of the ‘O’ as meaning organic or unpaid search, and the ‘M’ for money or paid search. We won’t cover SEM in this post, but will focus on SEO, particularly how to be indexed and rank well.

Some aspects of SEO are fairly straight-forward for engineers (most of the technical stuff), but other aspects are a lot more difficult (actually producing and publishing good content). Here we’ll focus mainly on the straight-forward, technical optimizations you should be doing.

Getting crawled and indexed

The absolute minimum your pages need is to be crawl-able and indexed by the Googlebot, and it’s surprisingly easy to get this wrong. Each page or page type that you want to rank should:

- Be allowed by robots.txt

- Have a stable, canonical URL

- Respond with HTTP 200, not 404 or 500

- Use server-side rendered HTML

- Be linked to from within your site

- Be in an XML sitemap

Let’s go over each of these in a bit more detail.

Robots.txt

Most medium to large sites have a text file located at /robots.txt that tells “good bots”, for example the Google web crawler, what pages they should or shouldn’t crawl. The file format is very simple, and is documented in detail on robotstxt.org and in Google’s documentation. A simple robots.txt file might look like this:

Sitemap: https://www.example.com/sitemap.xml

User-Agent: *

Disallow: /api/

Disallow: /staff/

This tells Googlebot (and other crawlers) two things:

- Here’s where the XML sitemap for this site lives.

- For all user agents (i.e., all crawlers), don’t crawl any URLs starting with /api/ or /staff/.

But you’ve got to be a bit careful — for example, what if a well-meaning engineer (who isn’t up on SEO or hasn’t read this article) decides to “block all those annoying bots” and adds “Disallow: /” to the file?

Or what if your CEO asks a developer to “create a page about me”, and the developer, without knowing about the robots.txt rule, decided to put it at /staff/billg? They won’t realize that it has no chance of being indexed.

This kind of thing happens more often than you think. Some companies use a robots.txt parsing library to add automated checks that ensure their important pages are always crawlable. At the least, you should put robots.txt in source control and have thorough review on all changes.

Obviously pages that you want crawled should be allowed by robots.txt. But you should actively disallow URLs that you don’t need crawled. For example, JSON API responses should not be crawled — Google only allocates a certain amount of crawl budget for your site, so you don’t want it crawling stuff it doesn’t need to.

Note that disallowing pages in robots.txt is not a security measure. Any bad bot or hacker can still crawl them. So, for example, /api/ requests disallowed by robots.txt still need to have secure authentication if the information behind them isn’t public.

Stable, canonical URLs

If you’re working with existing web apps, the URL structure may already be in place. But if you’re designing new URLs, here are some things to keep in mind:

One page, one URL: always serve a single page from a single, canonical URL. And by canonical here I don’t mean the rel=canonical link, but a single, normalized URL. For example, if you’re serving a page at /staff/billg, don’t also serve the content at /staff/gates/bill. If you do want to allow multiple URLs, 301 redirect others to the normalized address.

Handle trailing slashes: related to the above, don’t return HTTP 200 for a page at both /staff/billg and /staff/billg/. Instead, choose one of those as the canonical URL and 301 redirect other versions to that.

Semi-readable URLs: there’s a good amount of literature that advocates including descriptive keywords in the URL, and it’s become a “modern web” best practice. For example, prefer /articles/1234/seo-for-engineers over /articles/1234.

Include a resource ID: as in the example above, it makes things technically simpler if you include a resource ID like 1234 in the URL. Use the ID to actually look up the resource, and if the “seo-for-engineers” slug doesn’t match the article’s current slug, 301 redirect to the canonical URL. Many sites use this technique, including StackOverflow, TripAdvisor, and many others — it avoids the need for a database of historical URL changes or redirects.

If a web app’s URL structure is bad enough that it needs a redesign, it is possible to safely achieve this — you need to redirect the old URLs to the new ones using HTTP 301 Moved Permanently. Don’t do this too often, though!

One place you definitely should use 301s is redirecting your http:// site to your https:// one, and your non-www domain to the www one (or vice versa).

Clean HTTP responses

You want your pages to look as clean as possible to the Googlebot: returning HTTP 200s with no redirects. This avoids Google wasting crawl budget on retries, or in the worst case, Google penalizing your page rankings due to broken links or intermittent 500s. Things to avoid:

- HTTP 404: if a URL is returning a 404 Page Not Found incorrectly, either the link is broken, or the page handler is broken — both should be avoided. Of course, 404 is the correct code to return if there shouldn’t be a page at this location.

- HTTP 301: the 301 Moved Permanently is useful and serves an important purpose (see the previous section), but if your own pages are linking to a lot of redirected URLs, you should update those links.

- HTTP 500: Internal Server Error means Google is seeing a completely broken page. Hopefully your engineers are monitoring 500s closely in any case, but if not, now’s the time to start!

Read Moz’s guide to HTTP status codes for more information.

Server-side rendering

You should always serve server-rendered HTML for pages whose search-ability you care about. This is good not just for the user (faster to load, less battery drain running JavaScript) but also for the Googlebot.

“But,” someone will say, “Google now executes JavaScript.” This has been true since at least 2014 — Google does try to understand your pages better by running your JavaScript. However, it’s probably an order of magnitude more difficult to execute JavaScript than simply parse HTML: consider how much more CPU power you’d need to fire up V8 and run some JavaScript compared with parsing text out of the server-side rendered HTML.

There are a lot of caveats with relying on Google to execute your JavaScript (see the 2014 article linked above). Additionally, Google seems to parse HTML instantly, whereas JavaScript execution is a two-phase process which may be delayed significantly. So for best results, always serve your content in HTML generated on the server.

You can still use client-side tech like React to make your pages interactive, you just have to work a bit harder and enable server-side rendering. We saw significant ranking improvements at Compass when we switched from client-side React to server-side rendering a couple of years ago.

ReactDOMServer.renderToString(element)Render a React element to its initial HTML. React will return an HTML string. You can use this method to generate HTML on the server and send the markup down on the initial request for faster page loads and to allow search engines to crawl your pages for SEO purposes.

Internal linking

“Internal linking” is an SEO buzzword that simply means links from one page to another on the same site. Not only do such links help your users navigate your site, they also allow Google to crawl your site, and they spread “ranking power” around the site. Read more in the Moz article on internal links.

Internal linking is usually fairly simple to achieve, and you want to link from important pages to other important pages as much as (reasonably) possible. Examples of internal linking are:

- Breadcrumbs

- Navigation links in the header or footer

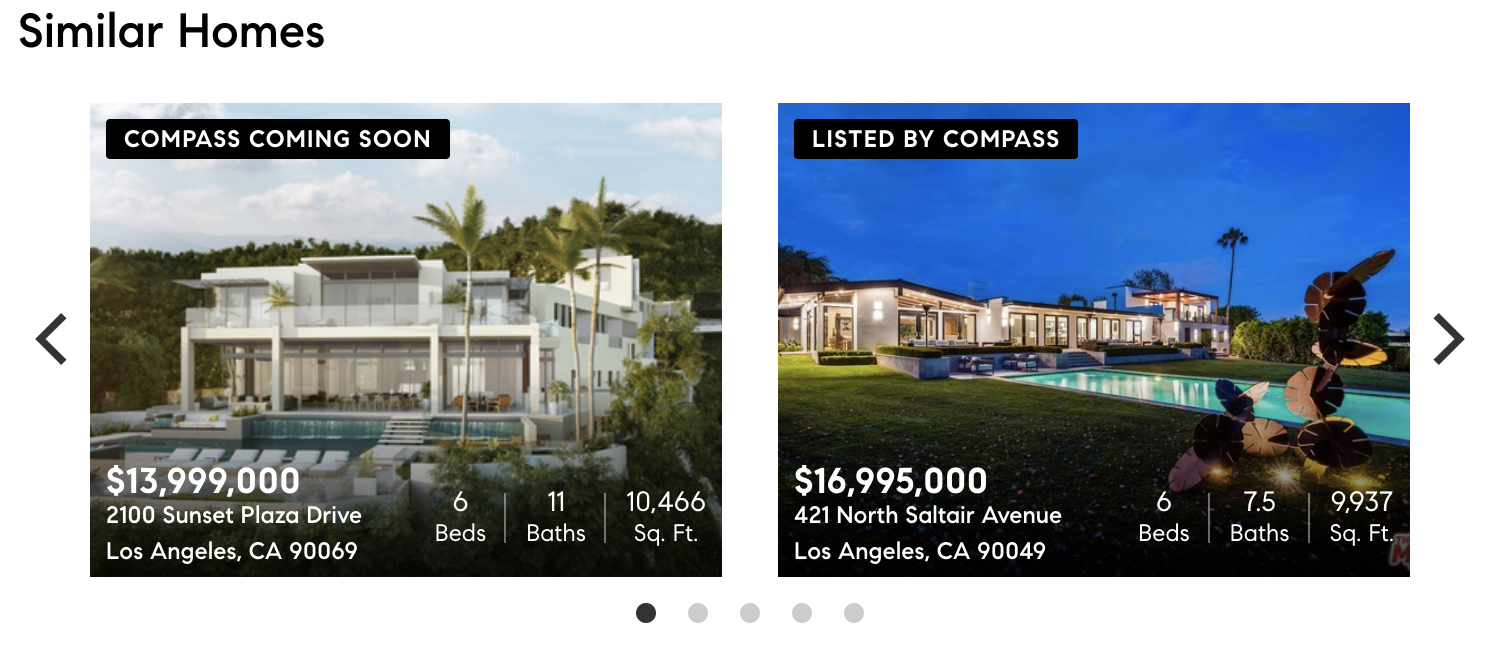

- Blocks of links helping the user navigate, and helping Googlebot find additional pages, e.g., links from a Compass listing to similar homes:

Most large sites also have an HTML sitemap, with links to all important pages on the site. These used to be more useful to the user, though now with search everywhere they’re arguably more of an SEO tool. However, it’s still considered good practice to have an HTML sitemap.

Compass and other real estate sites have an HTML sitemap that has a hierarchy of states, counties, and zipcodes — with the “leaf” pages linking to all the Compass-exclusive listings that are currently active. It’s one more way we expose our listing pages to Google.

XML sitemaps

Probably more important for large websites such as Compass are XML sitemaps. These are simple XML files, uploaded to Google Search Console or referenced in robots.txt, that simply list all the URLs on your site. This allows Googlebot to systematically find all of your product pages without necessarily following thousands of links.

Compass has a number of XML sitemaps (you can have more than one):

Sitemap: https://www.compass.com/sitemaps/exclusives/sales-sf/index.xml

Sitemap: https://www.compass.com/sitemaps/exclusives/sales-la/index.xml

Sitemap: https://www.compass.com/sitemaps/exclusives/sales-nyc/index.xml

Sitemap: https://www.compass.com/sitemaps/exclusives/sales-dc/index.xml

Sitemap: https://www.compass.com/sitemaps/exclusives/sales-other/index.xml

Sitemap: https://www.compass.com/sitemaps/exclusives/rentals/index.xml

...

Each sitemap index.xml is a file that links out to the actual sitemap.xml files, which look like so:

<urlset xmlns="http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9">

<url>

<loc>

https://www.compass.com/listing/101-old-mamaroneck-road-unit-1b4-white-plains-ny-10605/409187998570262817/

</loc>

<lastmod>2020-02-22T01:25:55.877000+00:00</lastmod>

</url>

<url>

<loc>

https://www.compass.com/listing/4641-south-lincoln-street-englewood-co-80113/414572085652655249/

</loc>

<lastmod>2020-02-22T01:25:16.710000+00:00</lastmod>

</url>

...

The “lastmod” field is optional, and allows Google to know when information on this particular page was last modified, to determine whether it should crawl it again.

You can read more about XML sitemaps in the Google docs.

Performing and ranking better

On-page basics

There are various basic things you need to do to make individual pages discoverable:

- Pages should be mobile-friendly. Google uses mobile-first indexing, so you should optimize your pages to work really well on mobile devices. Also, don’t serve different content on mobile devices and desktop. These things help not only Googlebot, but also the user.

- Each page should have a terse, specific **

** tag. This helps Google understand what the gist of the page is, and it’s generally shown prominently on the search results page. - Each page should have a brief but accurate summary in the meta description. Read Moz’s docs on meta description.

- Each page should have good structure: meaningful <h1> and <h2> headings, meaningful link text, images with good alt text, etc.

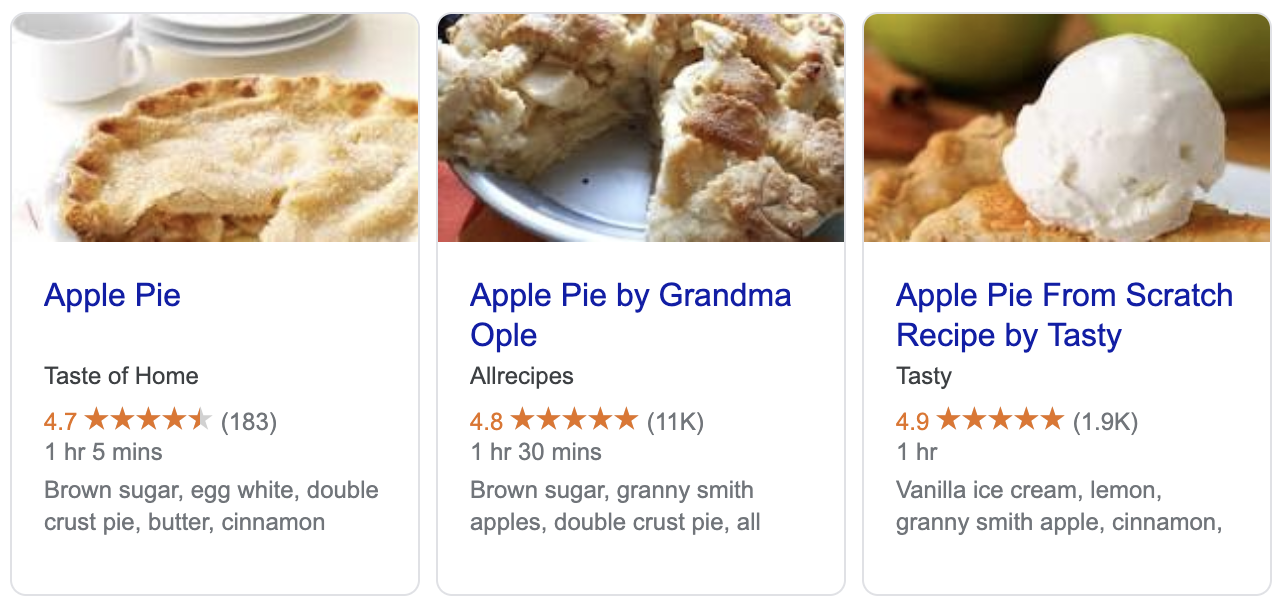

- For product pages and the like, use structured data such as JSON-LD to give Google more details. This helps Google understand the content in more detail, as well as powers the info boxes on search results pages, for example:

Page speed

In 2018, Google stated that they now use page speed as a factor to determine mobile page rankings, so it pays to make your pages fast.

Obviously the first thing is for the backend HTML to be returned in a timely fashion. That’s easy to measure, but it’s only the first step — client-side performance is taken into account too. There’s a lot of information from Google about how to measure and improve page speed, so I recommend you read that.

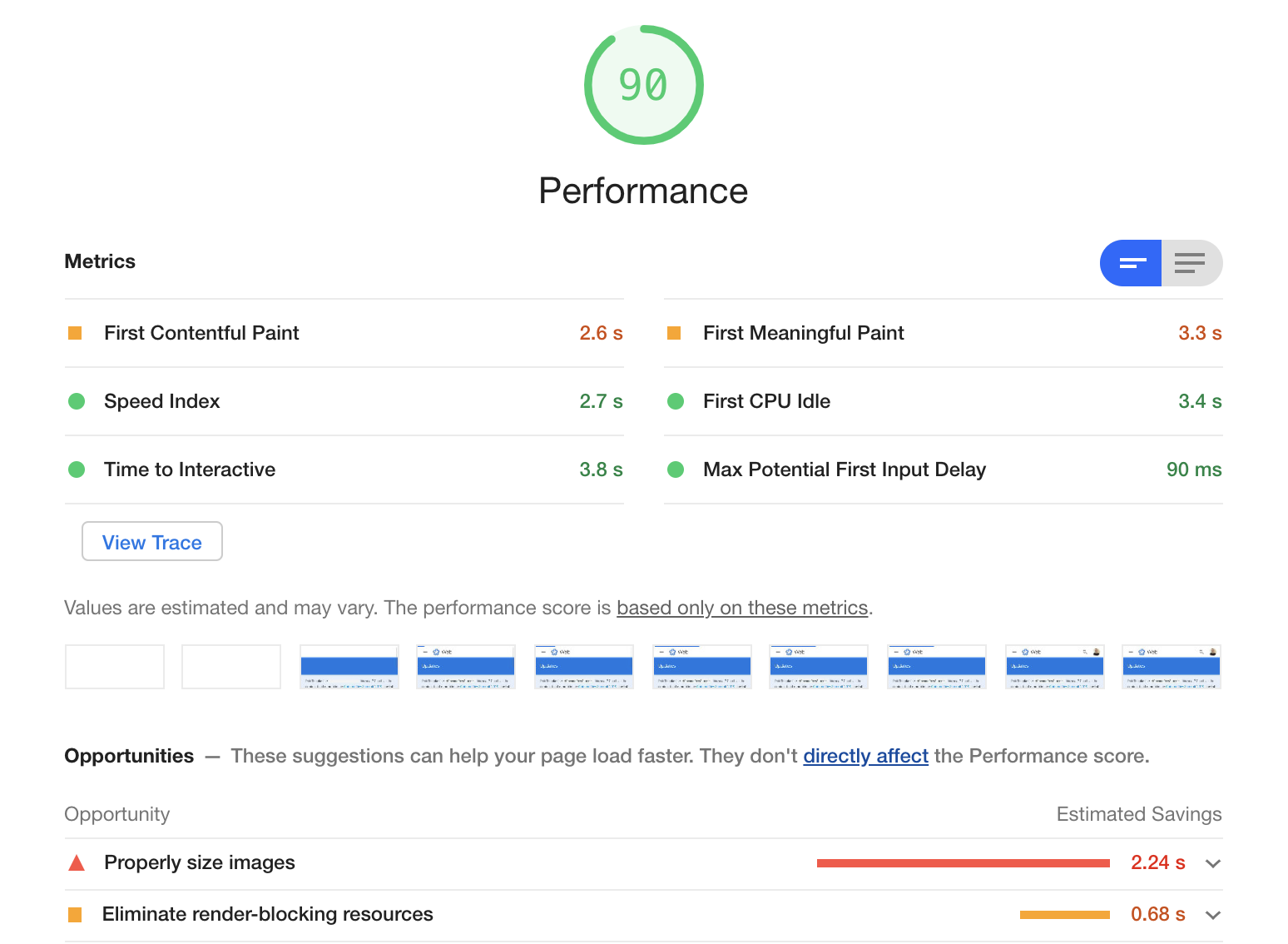

There are also great tools built right into Chrome that enable you to measure page speed as Google sees it, but locally. Right-click on a page, click on Inspect, go to the “Audits” tab and do a “Performance” audit on Mobile. You’ll get a nice-looking report with some (sometimes helpful) suggestions:

Google’s article about speed gets a 90/100 rating on their speed tester — not bad (or is that rigged? :-).

There are many things that go into page speed:

- Time to first byte: the networking time your servers take to return the first byte. After this, there’s HTML download time, which depends on the user’s bandwidth and the size of the HTML. Keep sizes down!

- First contentful paint: the time till the first render with real content from the DOM. This shows the user something is happening and Google uses this as one of its page speed signals.

- Time to interactive: the time till the user can actually do something with the page. Usually some JavaScript needs to execute before the page is interactive, so be careful about your JavaScript bundle size, startup time, etc.

- Static assets: your CSS and JavaScript should be cached with a long expiry time, ideally behind a CDN. They should also be as small as reasonably possible — beware large JavaScript packages like Moment.js!

- Image load time: you should serve reasonably sized images with correct caching headers, ideally behind a caching CDN. If your page references lots of large images, consider lazy-loading some of them.

Be careful! If you’re like most companies, you’re constantly iterating on and developing your pages, so they’re probably getting slower. You need to be vigilant about page speed in an ongoing way: measure when you add new features, additional calls to backend services, etc.

Link and domain authority

Google was birthed out of the PageRank algorithm (which, oddly enough, is named after Larry Page, not Web Page).

PageRank works by counting the number and quality of links to a page to determine a rough estimate of how important the website is.

In other words, if lots of other pages link to your page, it’ll rank better. And if those links are from high PageRank pages, even better. So you want to get authoritative websites to link to your pages as much as possible.

The exception to this is rel=nofollow links: “nofollow” is an attribute sites add to their <a> link tags to signal to Google not to follow or count this link in its ranking calculations. This is usually used for user-generated content such as blog or YouTube comments, which can be low quality and spammy.

If sites like this didn’t use rel=nofollow, spammers would submit hundreds of links to their pages to artificially boost their rankings. And that is exactly what happened before “nofollow” was introduced.

There’s also an SEO concept called domain authority, a Moz measurement that denotes how much overall authority a particular domain has (eg: nytimes.com has 95 out of 100, stackoverflow.com has 93, my small personal website has 37). This is not a Google measurement, but it seems to be a reasonable proxy for how important Google consideres a given domain.

Further reading

This article has mostly been discussing technical SEO improvements— things that engineers often have direct control over. But this is only half the story.

If you do all these technical SEO things, but don’t have good content, Google won’t rank you and nobody will use your site. Great SEO but terrible content is bad SEO. On the other hand, if you have good content, you’ll give it a much better chance of ranking well if you follow these techniques.

Google’s SEO Starter Guide is excellent reading from the horse’s mouth about these topics, as is the Moz Beginner’s Guide to SEO.

If you want to get in touch, see the banner at the top of our robots.txt!