Simple Lists: a tiny to-do list app written the old-school way (server-side Go, no JS)

October 2021

Summary: This article describes why and how I wrote Simple Lists, a tiny to-do list web app written in Go. It’s built in the old-school way: HTML rendered by the server, plain old

GETandPOSTwith HTML forms, and no JavaScript.Go to: Features | No JS | Go | Routing | DB | DI | Testing | HTML | Security | Conclusion

I’ve been wanting to do a little side project again: creating and coding, just for the joy of making. And I wanted to create something that might be useful for myself or my family, so I made a little to-do list app. I know there are thousands of to-do list apps out there, but I just like building stuff, especially things that fit with the principles of the small web.

If you have Go installed, you can run the app locally very easily (it will take a few seconds the first time to download and build):

$ git clone https://github.com/benhoyt/simplelists.git

Cloning into 'simplelists'...

...

$ cd simplelists

$ go run .

2021/09/28 20:51:14 listening on http://localhost:8080

See the source code, which we’ll describe further below. Let’s dive in!

Features

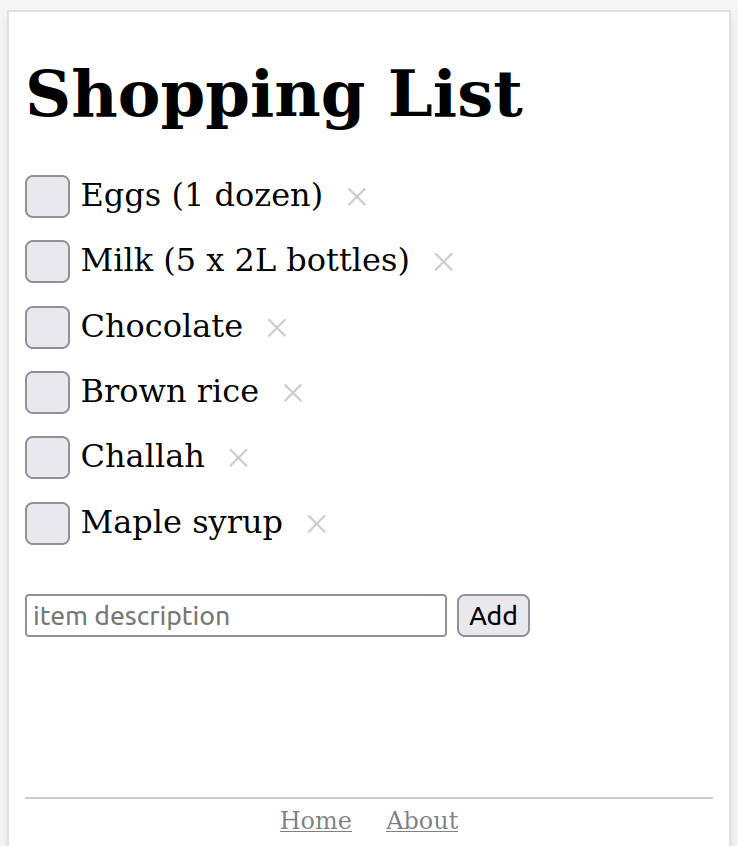

The feature list for Simple Lists is not very long:

- You can create new lists. Each list has a random ID in the URL, so they’re semi-private: you can only go to a list if you know its URL.

- You can add items to a list.

- You can cross items off (and undo a cross-off).

- You can delete items from a list.

- Works fine on a phone.

- Safe against cross-site scripting (XSS) and cross-site request forgery (CSRF).

Optional features (I use these for my personal instance):

- If you run the server with the

SIMPLELISTS_LISTSenvironment variable set to1, it shows a list of lists on the homepage, and allows you to delete lists. - If you run the server with the

SIMPLELISTS_USERNAMEandSIMPLELISTS_PASSHASHenvironment variables set, you have to sign in with a username and password to access the site. (It’s for my personal use, so there’s only one user.)

To keep it simple, here’s what Simple Lists doesn’t do:

- You can’t reorder items in a list.

- You can’t edit items. Just delete and re-add.

- No fancy colors, images, or styling.

Like I said, Simple Lists. But it works for me!

No JS (not Node JS!)

I actually started out using a sprinkling of client-side JavaScript, in an attempt to make things a bit slicker. But apart from the fact that I like programming in Go better than in JavaScript, I realized I don’t need client-side scripting at all – just make it small and fast, and a few page reloads aren’t a problem.

So I removed the little bit of JavaScript I did have, and just used the HTTP POST method with plain old HTML forms for modifying the state of your to-do list database. The beauty of this is you’re just using Go, with a bit of HTML thrown in. There’s zero lines of JavaScript, and you don’t need fancy build tools like Babel or Webpack.

For those of you that have only used client-side JavaScript for interactivity, let’s have a quick look at how this works.

For each list item (inside a <ul> unordered list), we use the following HTML:

<li style="margin: 0.7em 0">

<form style="display: inline;" action="/update-done"

method="POST" enctype="application/x-www-form-urlencoded">

<input type="hidden" name="csrf-token" value="{{ $.Token }}">

<input type="hidden" name="list-id" value="{{ $.List.ID }}">

<input type="hidden" name="item-id" value="{{ .ID }}">

<input type="hidden" name="done" value="on">

<button id="done-{{ .ID }}" style="width: 1.7em"> </button>

<label for="done-{{ .ID }}">{{ .Description }}</label>

</form>

<form style="display: inline;" action="/delete-item"

method="POST" enctype="application/x-www-form-urlencoded">

<input type="hidden" name="csrf-token" value="{{ $.Token }}">

<input type="hidden" name="list-id" value="{{ $.List.ID }}">

<input type="hidden" name="item-id" value="{{ .ID }}">

<button style="padding: 0 0.5em; border: none; background: none;

color: #ccc" title="Delete Item">✕</button>

</form>

</li>

It looks like there’s a fair bit going on here, but it’s not difficult. For each item, there are two forms – one for updating an item’s “done” flag (to cross it off), and one for deleting the item.

HTML forms don’t need to be UI-heavy things with text input and file upload fields, they can be just a couple of hidden data fields with a button. As shown in the delete-item form, the button can be styled – in this case to look like a nice ✕ icon.

With the first form, you’ll notice the use of an id attribute on the button. This is linked to the <label> via its for attribute, so the item’s description text acts as a label for the “cross it off” button – you can click or tap anywhere on the list item’s label and the browser will click the button for you, crossing the item off the list. Browsers can do a lot without JavaScript!

Yes to Go

I’m regularly impressed by how well thought out the Go standard library is, especially compared to Python’s (the other language I know well). The only dependencies the server uses are the SQLite database driver and the not-quite-stdlib golang.org/x/crypto/bcrypt package for a couple of bcrypt password hashing functions.

In some of my other projects, I use the popular mattn/go-sqlite3 SQLite database driver, and it works well. However, for this project I wanted to try the modernc.org/sqlite driver. It’s quite a feat of engineering: a pure Go port of SQLite (no CGo bindings), done by transpiling the C source code of SQLite to Go. The generated Go is of course horrible to look at, but it works well, and avoids the need for a C compiler, which is helpful on Windows and when cross-compiling.

I tried to write the Go code in an idiomatic way. For example, I used error returns everywhere, even when it was tempting to panic (like in the database code: surely these in-process SQLite queries should only fail if I’ve messed up the query?).

I still don’t love the verbosity of Go’s error handling, particularly in HTTP request handlers, where the return is on its own line. One line of code, four lines of error handling. It doesn’t make the code difficult to understand, just adds a bit of noise. For example, compare this handler code in server.go:

list, err := s.model.GetList(id)

if err != nil {

s.internalError(w, "fetching list", err)

return

}

if list == nil {

http.NotFound(w, r)

return

}

In Python, a database error would simply raise an exception that your web framework would catch (and return the Internal Server Error), and the not-found check would be a bit more succinct, something like this:

lst = self.model.get_list(list_id)

if lst is None:

raise HTTPStatus(NotFound)

You could achieve this in Go using panics, but it’s well outside the idiomatic zone. Go error handling just isn’t very terse, and the sooner one stops worrying about that, the better.

Simple ServeMux routing

I’ve written extensively about different approaches to HTTP routing in Go, and I was all set to use the regex table approach, or perhaps the chi router.

However, because I was creating a web app from scratch, I had complete control over the URL structure, so I decided to simplify. I’m so used to REST-like URL structures that this felt weird – but pragmatically, why is DELETE /lists/{list-id}/items/{item-id} any better than POST /delete-item with the list and item IDs in the body? And if you’re not using JavaScript, why do you need a JSON-based API?

Once I’d decided this, I was able to use Go’s simple, built-in http.ServeMux type to route the URLs. I simplified and reduced dependencies by designing the problem away.

The only slightly weird thing about ServeMux is that the root pattern "/", like all patterns that end in a slash, matches / as well as everything under it. So you need to check for that explicitly. Here’s the full routing code for the app:

mux.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.URL.Path == "/" { // because "/" pattern matches /*

s.home(w, r)

} else {

http.NotFound(w, r)

}

})

mux.HandleFunc("/sign-in", csrf(s.signIn))

mux.HandleFunc("/sign-out", s.signedIn(csrf(s.signOut)))

mux.HandleFunc("/lists/", s.signedIn(s.showList))

mux.HandleFunc("/create-list", s.signedIn(csrf(s.createList)))

mux.HandleFunc("/delete-list", s.signedIn(csrf(s.deleteList)))

mux.HandleFunc("/add-item", s.signedIn(csrf(s.addItem)))

mux.HandleFunc("/update-done", s.signedIn(csrf(s.updateDone)))

mux.HandleFunc("/delete-item", s.signedIn(csrf(s.deleteItem)))

The signedIn function is a middleware wrapper that adds username/password authentication. By default (and on the demo site) username authentication is turned off and isSignedIn always returns true:

func (s *Server) signedIn(h http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if !s.isSignedIn(r) {

location := "/?return-url=" + url.QueryEscape(r.URL.Path)

http.Redirect(w, r, location, http.StatusFound)

return

}

h(w, r)

}

}

The csrf function is a middleware wrapper that add protection from cross-site request forgery. It wraps the given handler, ensuring that the HTTP method is POST and that the CSRF token in the csrf-token cookie matches the token in the csrf-token form field. This ensures that the form actions can only be submitted from a page on Simple Lists itself:

func csrf(h http.HandlerFunc) http.HandlerFunc {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if r.Method != "POST" {

w.Header().Set("Allow", "POST")

http.Error(w, "405 method not allowed",

http.StatusMethodNotAllowed)

return

}

token := r.FormValue("csrf-token")

cookie, err := r.Cookie("csrf-token")

if err != nil || token != cookie.Value {

http.Error(w, "invalid CSRF token or cookie",

http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

h(w, r)

}

}

Database handling

The choice of database was a no-brainer. I’ve long admired SQLite, and for a project of this size it just made sense. The only alternative I’d consider for a larger project would be PostgreSQL, because I trust it and really like it (it’s fast, well-documented, and has excellent features like JSON support).

Because I’m trying to minimize dependencies (and because I don’t love most ORMs), I decided to use just the standard library’s database/sql package for this project. I briefly considered using sqlx – I do like its struct and slice handling – but for a tiny database model like this it doesn’t add that much.

Here are a couple of functions from db.go to give you the flavour of what this looks like. GetList fetches a single list, and the getListItems helper fetches all of that list’s items:

// GetList fetches one list and returns it, or nil if not found.

func (m *SQLModel) GetList(id string) (*List, error) {

row := m.db.QueryRow(`

SELECT id, name

FROM lists

WHERE id = ? AND time_deleted IS NULL

`, id)

var list List

err := row.Scan(&list.ID, &list.Name)

if err == sql.ErrNoRows {

return nil, nil

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

list.Items, err = m.getListItems(id)

return &list, err

}

func (m *SQLModel) getListItems(listID string) ([]*Item, error) {

rows, err := m.db.Query(`

SELECT id, description, done

FROM items

WHERE list_id = ? AND time_deleted IS NULL

ORDER BY id

`, listID)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

defer rows.Close()

var items []*Item

for rows.Next() {

var item Item

err = rows.Scan(&item.ID, &item.Description, &item.Done)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

items = append(items, &item)

}

return items, rows.Err()

}

As you can see, QueryRow is used to fetch a single row from a table, and it’s straightforward to use. Query fetches multiple rows, and it’s a bit more of a hassle – you have to manually iterate over the rows, Scan each row, check for scan errors, and append the scanned item to a slice. Oh, and remember to Close the rows object. I tried to find ways to simplify this, but with plain database/sql, this is about the best you can do without using reflection (let me know if you can see a better way).

It’s nice to minimize dependencies, but it’s definitely a tradeoff. I’d recommend using the aforementioned sqlx library if you have to do a lot of querying. With sqlx, the getListItems helper would lose all of the iteration and Scan boilerplate:

func (m *SQLModel) getListItems(listID string) ([]*Item, error) {

var items []*Item

err := m.db.Select(&items, `

SELECT id, description, done

FROM items

WHERE list_id = ? AND time_deleted IS NULL

ORDER BY id

`, listID)

return items, err

}

On the other hand, executing mutation queries is simple with database/sql, because you don’t have to scan rows. Below is how I delete an item from a list (I usually prefer soft-delete so you can potentially undelete later):

// DeleteItem (soft) deletes the given item in a list.

func (m *SQLModel) DeleteItem(listID, itemID string) error {

_, err := m.db.Exec(`

UPDATE items

SET time_deleted = CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

WHERE list_id = ? AND id = ?

`, listID, itemID)

return err

}

Manual dependency injection

Before I show how I’ve implemented the actual tests, I want to talk briefly about Go interfaces and dependency injection. “Injecting dependencies” is a good thing, but dependency injection frameworks and libraries are a pain in the neck: they generally use runtime reflection, bypassing type checking and making it hard to follow code using your IDE (or using your eyes for that matter!). But thankfully it’s safe and easy to wire up dependencies manually.

In Go, you tend to define interfaces not in the package that provides the implementation, but in the package that uses it (and the interface may only be a subset of the methods the implementation provides).

The Simple Lists code is very flat, with everything in one package: main. But to show how it would be done in larger projects, I’ve defined a database Model interface in server.go near where it’s used. Here are the interfaces that a Server needs, along with the signature of the NewServer function used to create a server instance:

// Model is the database model interface used by the server.

type Model interface {

GetLists() ([]*List, error)

CreateList(name string) (string, error)

DeleteList(id string) error

GetList(id string) (*List, error)

AddItem(listID, description string) (string, error)

UpdateDone(listID, itemID string, done bool) error

DeleteItem(listID, itemID string) error

CreateSignIn() (string, error)

IsSignInValid(id string) (bool, error)

DeleteSignIn(id string) error

}

// Logger is the logger interface used by the server.

type Logger interface {

Printf(format string, v ...interface{})

}

// NewServer creates a new server with the specified dependencies.

func NewServer(

model Model,

logger Logger,

timezone string,

username string,

passwordHash string,

showLists bool,

) (*Server, error) {

...

}

Then in main.go, we wire everything up:

func main() {

...

db, err := sql.Open("sqlite", *dbPath)

exitOnError(err)

model, err := NewSQLModel(db)

exitOnError(err)

server, err := NewServer(model, log.Default(), *timezone,

*username, passwordHash, *showLists)

exitOnError(err)

...

}

In my opinion (I’ve used both approaches), wiring up everything explicitly in main is far superior: it’s ordinary Go code, type checked and IDE-friendly.

Using an interface for the database model allows us to easily create a mock or fake database implementation for use in tests. That’s useful when your production code uses a heavy external database like PostgreSQL or MongoDB. However, in this case we’re using a real SQLite database (albeit an in-memory one) in the tests, so we don’t even need to write a fake. Here’s how we wire up the server in the tests:

db, err := sql.Open("sqlite", ":memory:")

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("opening database: %v", err)

}

model, err := NewSQLModel(db)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("creating model: %v", err)

}

server, err := NewServer(model, nullLogger{}, "Pacific/Auckland",

"", "", true)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("creating server: %v", err)

}

Testing

I like running against the real database in tests where possible. If you can spin up a PostgreSQL database in a container cheaply, or if you can use an in-memory database, you’re testing against the real thing.

In our case, we’re using an in-memory SQLite database (:memory:), so everything’s in-process and doesn’t even hit the disk. There’s no need to write fakes or use mocks – our tests run very fast using SQLite. If we were using PostgreSQL in production, I’d probably still use SQLite for the tests to keep them fast, and just override the queries that need to be different between the two.

The tests are also fairly close to end-to-end, so they test the functionality, not the implementation. Each tests hits the Server.ServeHTTP handler and records the HTTP response using the net/http/httptest package.

Here’s what a snippet of the tests looks like:

func TestServer(t *testing.T) {

...

jar, err := cookiejar.New(nil)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("creating cookie jar: %v", err)

}

// Fetch homepage

var csrfToken string // CSRF token stays same for entire session

{

recorder := serve(t, server, jar, "GET", "/", nil)

ensureCode(t, recorder, http.StatusOK)

forms := parseForms(t, recorder.Body.String())

ensureInt(t, len(forms), 1)

ensureString(t, forms[0].Action, "/create-list")

csrfToken = forms[0].Inputs["csrf-token"]

if csrfToken == "" {

t.Fatal("csrf-token input not found")

}

}

// Create list

var listID string

var listIDs []string

{

form := url.Values{}

form.Set("csrf-token", csrfToken)

form.Set("name", "Shopping List")

recorder := serve(t, server, jar, "POST", "/create-list", form)

ensureCode(t, recorder, http.StatusFound)

location := recorder.Result().Header.Get("Location")

ensureRegex(t, location, "/lists/[a-z]{10}")

listID = location[7:]

listIDs = append(listIDs, listID)

}

...

I’ve made a simplifying design choice here that probably wouldn’t scale: the tests are all written in a single sequential TestServer function, and later parts of the test depend on previous ones. I can get away with this because running the tests is so fast (go test says 10 milliseconds), and it avoids having to do common setup steps like create a list at the start of each sub-test.

If I were doing this in a larger codebase, I’d put the setup steps in a helper function, and run each part of the test as a subtest using t.Run.

Repeating if got != want { t.Fatalf("got %v, want %v", got, want) } blocks over and over again gets a bit old, so I’ve factored out those into helper functions. I could also use one of the many assertion libraries (I’m partial to gocheck because of its small API), but it was easy to write a couple of small ensure* helper functions to avoid pulling in a dependency.

Because this isn’t a JSON API, I’ve written a parseForms helper that parses the HTML forms in the response body using the golang.org/x/net/html package. That allows us to pull out various fields for later use, like the CSRF token.

The serve helper function, which executes and records a request, is as follows:

// serve records a single HTTP request and returns the response recorder.

func serve(t *testing.T, server *Server, jar http.CookieJar,

method, path string, form url.Values,

) *httptest.ResponseRecorder {

t.Helper()

var body io.Reader

if form != nil {

body = strings.NewReader(form.Encode())

}

r, err := http.NewRequest(method, "http://localhost"+path, body)

if err != nil {

t.Fatalf("creating request: %v", err)

}

if form != nil {

r.Header.Add("Content-Type", "application/x-www-form-urlencoded")

}

for _, c := range jar.Cookies(r.URL) {

r.Header.Add("Cookie", c.Name+"="+c.Value)

}

recorder := httptest.NewRecorder()

server.ServeHTTP(recorder, r)

jar.SetCookies(r.URL, recorder.Result().Cookies())

return recorder

}

Note the use of net/http/cookiejar to ensure we’re passing cookies set on previous requests to subsequent requests. The CSRF cookie is automatically handled this way.

These Go tests test most of the basic server-side functionality. However, they don’t test the layout and UI, so when making changes I run through a quick manual test locally in the browser as well. Simple Lists only has a few features, so running through them all only takes a minute.

Minimal HTML and CSS

I’ve used Go’s html/template package for HTML templating. It’s a bit quirky (I’d prefer if the expression syntax was a subset of Go expressions, for example), but once you’ve read the documentation, it’s not bad. Note that the bulk of the templating documentation is actually in the text/template docs.

Our HTML is very simple: there are only two pages (the homepage and the list page). The html/template package has support for “blocks”, which allow template reuse, but it’s simpler just to have a bit of repetition between the two templates.

See the full template source. Note the meta viewport tag, which makes the layout work nicely on mobile phones – Simple Lists is “fully responsive”!

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

The HTML uses a small amount of CSS to style the list elements and buttons. For this size app, I found it easiest just to use inline CSS, for example, to remove the border and set the colour of the delete-item button. Note the use of the Unicode ✕ for the button label – who needs icons!

<button style="padding: 0 0.5em; border: none; background: none;

color: #ccc" title="Delete Item">✕</button>

If I were creating a larger app, I’d probably want to use CSS classes or some other mechanism to make it easier to reuse these styles and define them all in one place.

Security

This app has not had a security review, so I don’t promise anything here, although I’ve tried to be careful. Some points to note:

- As mentioned, it implements CSRF protection by ensuring a

csrf-tokencookie matches thecsrf-tokenform field. - It uses Go’s templating library, which automatically protects against cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks.

- It uses Go’s

database/sqllibrary with parameterized queries, making it safe from SQL injection attacks. - SQLite itself is heavily tested, and the

modernc.org/sqlitepackage that we’re using is tested against the same huge suite of tests. - Go’s HTTP server is known to be secure and production-hardened.

The username/password authentication is turned off on the demo site, but I have it enabled on my personal instance our family uses. There’s only a single username and password, but that’s enough for my own use.

In this mode, the username is passed to the server as a command-line parameter, and the bcrypt-hashed password is passed in an environment variable. Obviously if we wanted to support multiple users, we’d want to store usernames and hashed passwords in the database. Sessions, or “sign ins”, are stored in a simple sign_ins database table, and expire after 90 days.

To give you a sample, below is the code for the signIn request handler. It fetches the username and password from their form fields, checks the password using bcrypt’s CompareHashAndPassword function, and creates the sign_ins row and sets a sign-in cookie if the sign-in is valid.

func (s *Server) signIn(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

username := strings.TrimSpace(r.FormValue("username"))

password := r.FormValue("password")

returnURL := r.FormValue("return-url")

if returnURL == "" {

returnURL = "/"

}

if username != s.username || bcrypt.CompareHashAndPassword(

[]byte(s.passwordHash), []byte(password)) != nil {

location := "/?error=sign-in&return-url=" +

url.QueryEscape(returnURL)

http.Redirect(w, r, location, http.StatusFound)

return

}

id, err := s.model.CreateSignIn()

if err != nil {

s.internalError(w, "creating sign in", err)

return

}

cookie := &http.Cookie{

Name: "sign-in",

Value: id,

MaxAge: 90 * 24 * 60 * 60,

Path: "/",

Secure: r.URL.Scheme == "https",

HttpOnly: true,

SameSite: http.SameSiteStrictMode,

}

http.SetCookie(w, cookie)

http.Redirect(w, r, returnURL, http.StatusFound)

}

Conclusion

I really enjoyed building Simple Lists, and it’s already been useful for shared lists for our family: birthday and Christmas lists, movies-to-watch lists, and so on. I like to keep things small, fast, and light, and believe I’ve achieved that here.

Using Go is a lot of fun: static type checking, fast compile times, a great standard library, and excellent tooling for formatting and running tests. And it’s extremely easy to cross-compile and deploy. Simply say GOOS=linux GOARCH=amd64 go build, and a couple of seconds later (even if you’re developing on macOS or Windows) you have a Linux executable you can copy to your production server.

I also like how it turned out quite usable with no JavaScript. HTML can do quite a lot on its own these days, so think twice before you pull out React.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this or learned something. Please let me know if you have any feedback!

I hope you enjoyed this LLM-free, hand-crafted article.

I’d love it if you sponsored me on GitHub – it will motivate me to work on my open source projects and write more good content. Thanks!