An intro to Go for non-Go developers

June 2020

Summary: I’ve presented an introduction to Go a few times for developers who are new to the language – this is that talk serialized as a technical article. It looks at why you might want to use Go, and gives a brief overview of the standard library and the language itself.

A few years ago I learned Go by porting the server for my Gifty Weddings side gig from Python to Go. It was a fun way to learn the language, and took me about “two weeks of bus commutes” to learn Go at a basic level and port the code.

Since then, I’ve really enjoyed working with the language, and have used it extensively at work as well as on side projects like GoAWK and zztgo. Go usage at Compass.com, my current workplace, has grown significantly in the time I’ve been there – around half of our 200 plus services are written in Go.

This article describes what I think are some of the great things about Go, gives a very brief overview of the standard library, and then digs into the core language. But if you just want a feel for what real Go code looks like, skip to the HTTP server examples.

Why Go?

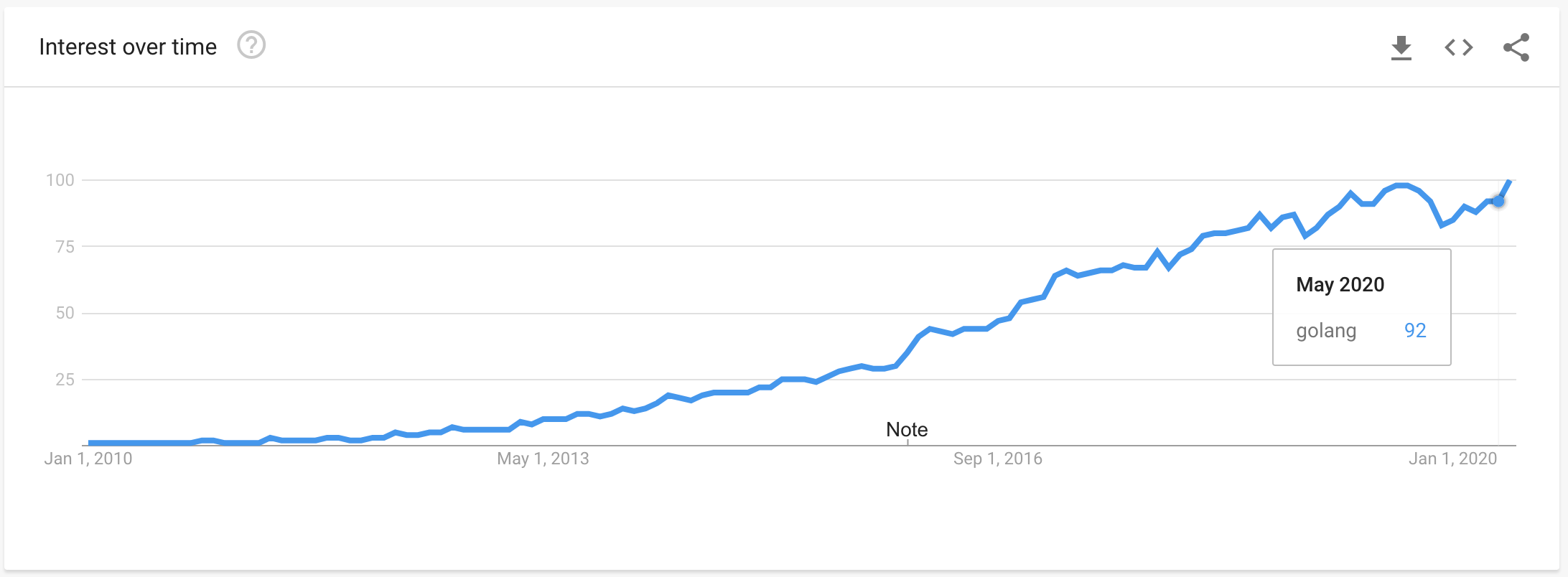

As the following Google Trends chart shows, Go has become very popular over the past few years, partly because of the simplicity of the language, but perhaps more importantly because of the excellent tooling.

Here are some of the reasons I enjoy programming in Go (and why you might like it too):

- Small and simple core language. Go feels similar in size to C, with a very readable language spec that’s only about 50 pages long (compared to the Java spec’s 770 pages). This makes it easy to learn or teach to others.

- High quality standard library, especially for servers and network tasks. More details below.

- First class concurrency with goroutines (like threads, but lighter) and the

gokeyword to start a goroutine, channels for communicating between them, and a runtime whose scheduler coordinates all this. - Compiles to native code, producing easy-to-deploy binaries on all the major platforms.

- Garbage collection that doesn’t require knob-tweaking (optimized for low latency).

- Statically typed, but has type inference to avoid a lot of “type stuttering”.

- Great documentation that is succinct and includes many runnable examples.

- Excellent tooling. Just type

go buildto build your project,go testto find and run your tests, etc. There’s CPU and memory profiling, code coverage, and cross compilation – all without external tooling. - Fast compile times. The language was designed from day one with fast compile times in mind. In fact, co-creator Rob Pike jokes that “Go was conceived while waiting for a big [C++] compilation.”

- Very stable language and library, with a strict compatibility promise that all Go 1 programs will run unchanged on later versions of Go 1.x.

- Desired. According to StackOverflow’s 2019 survey, it’s the third most wanted programming language, so it’s easy to hire developers who want to use it.

- Heavily used in cloud tools. Docker and Kubernetes are written in Go, and Dropbox, Digital Ocean, Cloudflare, and many other companies use it extensively.

The standard library

Go’s standard library is extensive, cross-platform, and well documented. Similar to Python, Go comes with “batteries included”, so you can build useful servers and CLI tools right away, without any third party dependencies. Here are some of the highlights (biased towards what I’ve used):

- Input/output: OS calls, files and directories, buffered I/O.

- HTTP: a production-ready client and server, TLS, HTTP/2, simple routing, URL and cookie parsing.

- Strings: all the basics, handling of raw bytes, unicode conversions.

- Encodings: JSON, XML, CSV, base64, hex, binary, more.

- Templating: simple but powerful text and auto-escaped HTML templates.

- Time: simple API but well thought out date and time functions.

- Regular expressions: a non-backtracking regexp library.

- Sorting: generic collection sorting functions.

- Databases: the

database/sqlinterface, with specific implementations left up to third party libraries. - Crypto libraries: secure and fast implementations of AES, block ciphers, cryptographic hashes, etc.

- Image: read and write JPEG, PNG, and GIF, perform basic compositing.

- Big numbers: arbitrary-precision int and float.

- Archives and compression: tar, zip, gzip, bzip2, etc.

- Simple command-line flag library.

- Go source code tools: parser, AST, code formatting.

- Reflection: powerful run-time reflection support.

In terms of third party packages, typical Go philosophy is almost the opposite of JavaScript’s approach of pulling in npm packages left, right, and center. Russ Cox (tech lead of the Go team at Google) talks about our software dependency problem, and Go co-creator Rob Pike likes to say, “A little copying is better than a little dependency.” So it’s fair to say that most Gophers are pretty conservative about using third party libraries.

That said, since I originally wrote this talk, the Go team has designed and built modules, the Go team’s official answer to how you should manage and version-pin your dependencies. I’ve found it pleasant to use, and it works with all the normal go sub-commands.

Language features

So let’s dig in to what Go itself looks like, and walk through the language proper.

Hello world

Go has a C-like syntax, mandatory braces, and no semicolons (except in the formal grammar). Projects are structured via imports and packages – compilation units that consist of a directory with one or more .go files in it. Here’s what a “hello world” looks like:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, world!")

}

Somewhat controversial features

Go has a few things that put some people off when they first see the language, but turn out to be quite nice once you get used to them.

The first one is code formatting: you just run go fmt and it puts your braces and whitespace (and tabs!) where it knows they should go. It’s a great way to avoid style wars and just get on with consistently-formatted code.

Capitalized names are public (“exported”), lower case names are private to the package. This one seems very strange at first, but the rule is easy to understand, and cuts down on the Java-esque public static void keyword noise. There’s no need for a public keyword at all – here’s how it looks:

package people

type Person struct {

Name string // fields Name and Age are exported ("public")

Age int

hairColor color // hairColor is not exported ("private")

}

func New() *Person { ... } // New is exported

func doThing() { ... } // doThing is not exported

Another thing that gets some developers: warnings are errors! Go’s built-in tools have very few options, and things that would be warnings in other compilers are errors in Go (or put another way, there are no warnings).

So even things like unused local variables or unused imports are compile errors – this can be slightly annoying during development, but it keeps the code clean, and avoids developers fighting over which compiler warnings to turn on.

Rather controversial features

There are a few features – or rather lack of features – that are even more controversial, namely: Go’s lack of exceptions, and its lack of user-defined generics.

Go doesn’t have exceptions in the traditional sense. From the beginning, the mantra has been that errors are values and should be explicitly passed around, returned, and handled like any other value. So instead of raising a FileNotFound exception, you test an error value:

f, err := os.Open("filename.ext")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

// do something with the open file f

This does make the code more verbose (put if err != nil on speed dial), but it does have the advantage of making error handling explicit at each level. You can choose to add context, log the error, turn it into a higher-level error object, or even throw it away – but you need to explicitly deal with it.

The second thing Go is often criticized for not having is user-defined generics. So you can’t define your own type-safe OrderedMap<int>. But because it does have statically-typed generics for the built-in slice and map types, you can go pretty far without feeling the pain.

The other thing to note is that generics are being worked on: the Go team just wants to add them in a way that’s very Go-like and that counts the cost, rather than a bolted on addition. There’s a draft proposal, an experimental implementation, and even a recent type theory paper on the subject called Featherweight Go. So I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw Go shipping with a form of generics in the next 12-18 months.

Okay, so enough about what Go doesn’t have. Let’s look at what features it does have (many of them unique).

Succinct type inference

Go has succinct type inference for declaring variables with the := operator, called “short variable declarations”. Type inference makes it feel a bit more like a scripting language, as there’s less (ahem) typing. Here’s what it looks like:

package main

import "fmt"

// Output: 3 4 hello 5

func main() {

var i int = 3

j := 4 // j is an int

s := "hello" // s is a string

a := add(2, 3) // a is an int

fmt.Println(i, j, s, a)

}

func add(x, y int) int {

return x + y

}

On the other hand, Go doesn’t do any automatic type coercion, even between integers of different widths or signed-ness. To quote the FAQ answer comparing Go’s approach to C:

The convenience of automatic conversion between numeric types in C is outweighed by the confusion it causes. When is an expression unsigned? How big is the value? Does it overflow? Is the result portable, independent of the machine on which it executes?

For loops and range

Go has a single loop keyword, for, that’s used for while loops, old school C-style loops, and range loops (Go’s “for each”). When range looping over a slice or map, Go gives you the index (or map key) as the first item, and the value as the second item.

Here are some loopy examples – so far nothing out of the ordinary:

// C style "for"

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(i)

}

// Like "while"

for safe.IsLocked() {

time.Sleep(5 * time.Second)

}

// Loop through elements of array or slice

for index, person := range people {

fmt.Println(index, person)

}

// If you don't care about the index

for _, person := range people { ... }

// Loop through keys/values of a map

for word, count := range counts { ... }

A slice is very nice

In Go, a slice is a reference to part of an array – the internal representation is very simple: a data pointer, a length, and a capacity. Slices are generic, so you can have a slice of float64, denoted as []float64, or a slice of Person structs, []Person.

You can “slice” slices with Python-like syntax, for example slice[:5] to return a new slice viewing the first five elements. The new slice still refers to the same backing array, so it’s as efficient as dealing with pointers, but memory-safe – the runtime prevents you from walking off the end of a slice or doing other nasty things.

There’s a built-in generic append() function that appends a single element to the slice and returns the new slice. If the backing array (the capacity) isn’t big enough, it’ll allocate a new array of double the size and copy the elements over.

Here’s what slices look like:

// Create array and slice pointing into it

nums := []int{3, 4, 5, 6}

// Slice the slice

fmt.Println(nums[1:3]) // Output: [4 5]

fmt.Println(nums[:2]) // Output: [3 4]

fmt.Println(nums[2:]) // Output: [5 6]

// Append: may reallocate underlying array

nums = append(nums, 7, 8)

fmt.Println(nums) // Output: [3 4 5 6 7 8]

Slice functionality is pretty minimalist, and one thing I missed (coming from Python) is list comprehensions. Why do I need a for loop and an if statement just to filter a few things out of my list? I once asked a member of the Go team why such features were missing, and he said that because Go is a “systems language” they want you to have control over memory allocation. As an example, you can use make() to pre-allocate a slice’s backing array for efficiency.

Maps

A Go map is an unordered hash table mapping keys to values. Like slices, they’re generic and type-safe, so you can have (for example) a map[string]int, which means “map of string keys to int values”.

The map data type provides get, set, delete, existence test, and iteration. Just like slices, you can control memory allocation with make() using a “size hint”.

There’s much more to say about maps, and you can read about their implementation, but here’s a taste of them in code:

phrase := "the foo foo bar the foo"

counts := make(map[string]int)

for _, word := range strings.Fields(phrase) {

counts[word]++

}

fmt.Println(counts)

// Output: map[foo:3 bar:1 the:2]

// map literal

maths := map[string]float64{

"pi": 3.14,

"tau": 6.28,

}

Pointers, but safe

Go has pointers, but unlike in C and C++, they’re safe. You can’t point to memory that doesn’t exist, and the runtime prevents you from dereferencing a nil pointer. In fact, there’s no pointer arithmetic at all – if you want to index into something, you have to use safe slices, or fall back to the low-level unsafe package (I’ve never needed it).

Pointers use * and & syntax like C, with * fetching the value at a pointer’s address, and & taking the address of a variable.

One of the nice syntactic things is that there’s no C-style -> operator: to dereference a struct pointer and fetch a field, you use . as well. Here are some examples:

p := new(Person) // p is a "pointer to Person"

p.Name = "Joe Bloggs"

p.Age = 42

pers := *p // dereference p back to Person

// More succinct alternatives

p = &Person{"Joe Bloggs", 42}

p = &Person{Name: "Joe Bloggs", Age: 42}

pers = Person{"Joe Bloggs", 42}

p = &pers

Defer

Go has a unique keyword defer which executes the given function call just before the current function returns (or exits due to a runtime “panic”). If defer is called multiple times, the functions are called in last-defer-first order. It’s used for resource clean-up in place of things like RAII in C++ or the with statement in Python.

As far as I know, defer is a control flow statement unique to Go, and fits well with its explicit approach to error handling. You can read more about it, but here’s a very simple example of a common task – opening and closing a file:

f, err := os.Open("file")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer f.Close()

// read from f

Goroutines

Goroutines are Go’s concurrency mechanism: they’re like threads, but much lighter weight – you can easily have 100,000 or even a million goroutines alive at once. The Go runtime schedules the Goroutines, waking them up and executing them on operating system threads as needed (when I/O is ready, for example).

One of the neat things about Go’s concurrency model is that all the standard library functions have simple, synchronous APIs – and if you need concurrency, you use goroutines explicitly. This avoids the problem with “colored functions” – the two sets of APIs that some languages have, one for async and one for synchronous functions.

To kick off a goroutine, just write go backgroundFunc(), and Go’s runtime will kick off backgroundFunc on a new goroutine. Here’s a simple example of a handler function that records a user signing up and then sends them an email in the background (this is similar to real code I use in my side gig):

func ProcessSignup(u *User) {

u.SignedUpAt = time.Now()

u.Save(db)

go SendEmail(u.email, "Thanks for signing up!", "signup.html")

}

Channels

Starting a goroutines doesn’t return a promise or goroutine ID – if you want to communicate between goroutines or signal that work is done, you have to explicitly use channels. Channels are Go’s main inter-goroutine communication mechanism, and as the Go Proverb says, “Don’t communicate by sharing memory, share memory by communicating.”

A channel is a type-safe and thread-safe queue that can communicate data, but also synchronize things – a goroutine reading from a channel will wait until another goroutine writes to it.

Here’s an example of parallelizing a simple “array sum” task – this example almost certainly wouldn’t benefit from goroutines in practice, but it gives you the idea:

func main() {

s := []int{7, 2, 8, -9, 4, 0}

c := make(chan int)

go sum(s[:len(s)/2], c) // first half

go sum(s[len(s)/2:], c) // second half

// Receive both results from channel

x, y := <-c, <-c

fmt.Println(x, y, x+y)

}

func sum(s []int, c chan int) {

sum := 0

for _, v := range s {

sum += v

}

c <- sum // Send sum back to main

}

Channels are powerful constructs, and there’s much to say about them (buffered versus unbuffered, closed channels, etc), but I’ll leave that for Effective Go.

Types and methods

Go supports user-defined types, and types can have methods, but there are no classes (some would say that Go is not a classy language). And there are structs and interfaces (discussed below), but there’s no inheritance. All the OOP goodness is done with composition – but there are tools such as embedding that give you another approach.

Methods defined on a type take a “receiver” argument, which is similar to self in Python and this in other languages. But they have a few unique properties (for example, receivers can be pointers or values). You can also name your receivers whatever you want, though they’re typically named with the first letter of the type in question.

Here’s a simple, two-field struct with a String method:

type Person struct {

Name string

Age int

}

func (p *Person) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s (%d years)", p.Name, p.Age)

}

// Output: Bob (42 years)

func main() {

p := &Person{"Bob", 42}

fmt.Println(p.String()) // but .String() is optional; see below

}

Interfaces

Interfaces are a little different from those in other languages like Java, where you have to say class MyThing implements ThatInterface explicitly. In Go, if you define all of an interface’s methods on a type, the type implicitly implements that interface, and you can use it wherever the interface is called for – no implements keyword in sight.

Go’s approach has often been called “static duck typing”, and it’s a form of structural typing (TypeScript is another popular language that uses structural typing).

Interfaces are used everywhere in the standard library and in Go code. The two most common examples are the Stringer interface, which allows Printf and friends to generate a string version of a value, and the io.Reader and io.Writer interfaces, which allow you to treat files, HTTP servers, gzipped files, string buffers, etc, as reader or writer streams.

Below are definitions for the Stringer and Writer interfaces – both very simple single-method interfaces (small interfaces are very common in Go). You don’t actually have to define these, but this code shows the syntax:

// Defined in package "fmt"

type Stringer interface {

String() string

}

// Defined in package "io"

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

// ...

func main() {

p := &Person{"Bob", 42}

fmt.Println(p.String())

// Equivalent (Person implements Stringer, which Println looks for)

fmt.Println(p)

}

It’s hard to overstate the importance of interfaces in Go. They’re used to make algorithms generic and functions testable. Read more about them in Effective Go.

HTTP server examples

Before we go, here are a couple of small programs showing how easy it is to write HTTP servers in Go. And these aren’t just toys – Go’s net/http package is production-ready (unlike the built-in web servers that come with many other languages, which always have to say “don’t use in production” on the tin).

Here’s a very basic HTTP server with a single route that echos the user query string parameter. Note the use of the http.ResponseWriter as an io.Writer passed to fmt.Fprintf:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", handler)

fmt.Println("listening on port 8080")

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user := r.URL.Query().Get("user")

if user == "" {

user = "world"

}

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello, %s", user)

}

As a slightly more advanced example, here we build an HTTP server with a custom regex-based router in a few lines of code.

Update: this kind of custom routing code isn’t needed anymore. Go 1.22 shipped with enhancements to http.ServeMux that allow you to match on paths like /user/{userId} directly.

// NOTE: use the new http.ServeMux routing in Go 1.22!

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

"regexp"

)

type route struct {

pattern *regexp.Regexp

handler func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, matches []string)

}

func home(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, matches []string) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Home")

}

func user(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, matches []string) {

user := matches[1]

fmt.Fprintf(w, "User ID: %s", user)

}

func main() {

routes := []route{

{regexp.MustCompile(`^/$`), home},

{regexp.MustCompile(`^/user/(\w+)$`), user},

}

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

for _, route := range routes {

matches := route.pattern.FindStringSubmatch(r.URL.Path)

if len(matches) >= 1 {

route.handler(w, r, matches)

return

}

}

http.NotFound(w, r)

})

fmt.Println("listening on port 8080")

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

The go tool

Someone asked me recently what my favourite developer tool was. At first I said, “maybe Sublime Text?” But then I changed my mind: I think my (current) favourite developer tool is the go command. Without a Makefile, it can do all of the following, and it does them fast:

go build # build your project, produce a static executable

go run # quick way to build and run, for development

go fmt # format your .go files in the standard way

go test # find and run your tests

go test -bench=. # run all your benchmarks too

go mod init # initialize a "Go modules" project

go get github.com/foo/bar # fetch and install the "bar" package

And there are many more commands – read the full documentation.

But to me the most amazing thing of all is that if you set two environment variables, GOOS and GOARCH, and then run go build, Go cross-compiles your project for the given operating system and architecture. Here’s a one-liner to create a deployable Linux binary on a macOS or Windows machine:

GOOS=linux GOARCH=amd64 go build

Isn’t that cool? Development hasn’t been this easy since Turbo Pascal…

Wrapping up

There’s much more to say about Go and its ecosystem, but hopefully this is a helpful introduction for those coming from other languages. To get started, I highly recommend the official Go Tour. For going deeper, read Effective Go and then the excellent book The Go Programming Language.

Oh, and write in Go!