History’s peacocks

In one sense it would be easy to write a history of fashion in Europe over the last thousand years, tracing the sometimes bewildering numbers of fabrics, cuts, styles, lengths and colours which drifted in and out of fashion during this period. However, a simple narrative like that would yield only a very simple conclusion: fashions change. We often associate fashions with fads, thinking of fashion as being merely external, and often ridiculous in its fickleness. However, if we hold too fast to this association, we will miss the important fact that, in the past, clothing was taken very seriously indeed.

People of the past realized what we have perhaps forgotten: clothing is the bearer of many significant cultural messages. Dress could signal class, profession, religion, wealth, race, virtue and, most obviously, gender. Furthermore, people in the past had a much keener appreciation for the truth of the old proverb that “clothes maketh the man”. Clothing did not so much conceal the real person underneath – they helped to create his social persona.

Taking the political and cultural importance of dress as its theme, this article will provide a brief survey of some of the high and low points of fashion in Europe, from the Middle Ages till the modern period. We usually associate addiction to fashion with women, but I will concentrate mostly on the clothing that men wore, and how men’s dress helped to both reflect and constitute the cultural values of past societies.

What not to wear, medieval-style

Authorities in medieval societies were serious enough about clothing to issue literally hundreds of sumptuary laws during the period. Sumptuary laws are essentially laws which regulate consumption. Although they were also common in ancient Greece and Rome, those were more likely to restrict elaborate wedding and funeral celebrations than clothing. However, in Europe in the Middle Ages, by far the most common type of sumptuary laws were those prohibiting certain articles of dress, or restricting certain fabrics and styles to particular classes.

These restrictions included reserving expensive furs like ermine for the nobility, prohibiting maidservants wearing trains on their dresses, demanding that peasants wear only black or grey, and requiring prostitutes to wear certain clothing. Other more peculiar laws included the edict in 14th-century Venice forbidding citizens from wearing dark blues and greens. While the aim of the city fathers in this case was to cheer up the plague-stricken city by encouraging everyone to wear bright colours, the other examples make it clear that the main purpose behind sumptuary laws was to preserve and make visible the social hierarchy. We can see that clothing not only reflected social realities (the difference in status between prostitutes and noblewomen, for example), but also helped to maintain those social realities (for example, by ensuring the continuing distinction between merchants and lords).

The French know how to dress

As the medieval period progressed, the nobility began to pay more and more attention to fashion. With the ascendance of the Burgundian court in the 14th century, French fashions came to dominate the sartorial senses of European aristocrats. Court culture and the ideal of courtly love also helped to promote interest in rich clothing. In the early medieval period knights had been little more than mercenaries, but in this later period there was an increasing obligation to spend a lot of time sitting around looking splendid – noblemen had to spend much more time thinking about fashion and much more money appearing fashionable.

These new courtly fashions replaced the earlier unisex tunic. The famously grumpy chronicler Orderic Vitalis complained about the “over-tight shirts and tunics” which had become fashionable among young noblemen of his day. Tunics had become shorter and more colourful, and shirts and pants were slit to show a glimpse of flesh. The most fashionable shoes were those with very long toes which often had to be tied back to the ankle to enable walking (Orderic Vitalis rather maliciously claimed that they were invented by Fulk of Anjou to disguise his bunions).

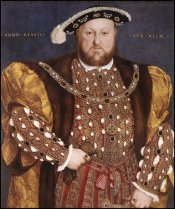

Court dress reached the greatest heights of splendour during the early modern period in Europe (1450–1750). The courts were cultural pioneers, and at court the best music, art, literature and dress was displayed. The sartorial glory of Henry VIII and the famously brilliant tailoring modelled by Louis XIV illustrate the importance of magnificent dress during this period.

The suit is born – in three pieces

Beginning in England, this emphasis on rich and splendid clothing began to change during the 16th century – at least for men. A famous entry in Samuel Pepys’ diary records the invention by Charles II of one of the most enduring items of male clothing: the three-piece suit. Pepys writes that Charles declared “his resolution of setting a fashion for clothes, which he will never alter. It will be a vest, I know not well how; but it is to teach the nobility thrift, and will do good.” Thus the origins of the suit, and the very beginnings of what would flower in the 18th century as the “Great Masculine Renunciation”, when refinement in dress replaced overt display of wealth as the standard of male chic.

Historians have explained that, during the Restoration (1660 onwards), the crown was looking for a more stable foundation upon which to establish its rule. The court of Charles I was famous for its extravagance, and Charles II’s innovation was designed to show that his rule would be characterised by greater sobriety and manly restraint. It is significant that he turned to an article of clothing, both to reflect these new values and to impress them upon the nobility. He believed that this new type of clothing would create a new type of man.

Throughout the following two centuries, western Europe was consumed by discussions about who was eligible for political and civil rights. It is within this context that the Great Masculine Renunciation emerged, and with it the suit we are familiar with today. As the emerging middle classes became wealthier, money was now no longer a sufficient distinction between the nobility and the commoners. Furthermore, while conspicuous consumption was important and virtuous during the 16th and early 17th centuries, in this later period the great political vices were effeminacy and luxury. Placing too much value on rich clothing was considered a sign of addiction to luxury and labelled as “effeminate” (hardly fair, given the splendid adornment of early modern lords).

As a result, both aristocrats and the rising middle class began to adopt the suit as a mark of restraint. Aristocrats sneered that the middle classes were vulgar upstarts and addicted to luxury. They adopted the suit, advertising their own refinement. The professional or industrialist condemned the effete aristocrat (with wig, powder and lace) and also adopted the suit, advertising his manly sobriety. In the war over who was to wield power in Britain, the suit became a mighty weapon. By the 19th century, captains of industry, city clerks, statesmen, great landowners, and men of the royal family were all wearing the suit.

Liberty, equality, and the right pair of pants

Across the Channel, the great shift in men’s fashions came, unsurprisingly, with the French Revolution. The great symbolic weight attached to clothes is shown by the fact that one of the most influential factions here was named after what people wore (or rather, what they did not): the sans-culottes. The culottes were knee breeches commonly worn by the nobility, and so the radical sans-culottes wore ordinary workers’ trousers to testify to their appropriately lowly background. Similarly, the revolutionary cockade (a knot of ribbons in revolutionary colours, usually attached to a hat) became an important symbol of patriotism, and failure to wear it became dangerous. There was also much serious talk about establishing a uniform for the Revolutionary Assembly (think togas). While this may seem a little ridiculous, the revolutionaries knew that as the sessions of the Assembly were public, a convincing outward appearance (aided by appropriate costume) was essential to establish the new government’s legitimacy in the minds of the populace.

In a word, fashion counts

This brief sketch of a thousand years of men’s fashions has demonstrated the extent to which clothing can bear some fairly hefty political burdens. I could go on by discussing the economic importance of the dress trade in Europe (it was no accident that the Industrial Revolution began with Britain’s textile industry), not to mention the debates over priests’ vestments, or the anatomical transmogrifications which the Victorians tried to enact with the corset. However, hopefully it’s been a good reminder about the importance of clothing and the signals our fashions choices transmit. Perhaps it will help us think more critically about what our clothes say in this modern era of fashion.

Laurel Flinn is studying for her PhD in history at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA. She enjoys listening to indie music, skiing and having pointy-headed discussions about historiography. She owns a genuine pair of lederhosen.